The U.S. power grid is suffering a decade-high surge in attacks as extremists, vandals and cyber criminals increasingly take aim at the nation’s critical infrastructure.

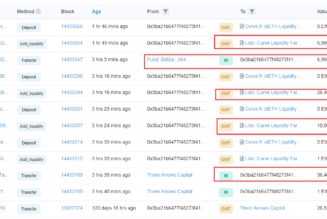

Physical and computerized assaults on the equipment that delivers electricity are at their highest level since at least 2012, including 101 reported this year through the end of August, according to federal records examined by POLITICO. The previous peak was the 97 incidents recorded for all of 2021.

This year’s tally doesn’t even include 2022’s most visible attack — the shootings of two Duke Energy substations that knocked out power to 45,000 people in Moore County, N.C.

And the lights went dark on Christmas Day for 14,000 customers in Washington state after four Tacoma Public Utilities and Puget Sound Energy substations were vandalized, with no suspects in custody, the Pierce County Sheriff’s Department said in a statement on Sunday.

“It is unknown if there are any motives or if this was a coordinated attack on the power systems,” the department said.

Authorities have yet to identify any suspects in the North Carolina attack, and have only been able to speculate about the motive. But white nationalists, neo-Nazis and other domestic extremists seeking to sow unrest have taken responsibility for other high-profile attempts to take down swaths of the grid — prompting security experts to grow increasingly concerned about the U.S. electricity system’s vulnerability.

The risks have also caught the attention of federal regulators who oversee the interstate power network.

“Is there something more sinister going on?” Richard Glick, chair of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, told reporters last week. “Are there people planning this?… I don’t think anyone knows that right now. But there’s no doubt that the numbers are up in terms of reported incidents.”

Adding to those worries: The number of potential attack points for the grid is set to increase as the Biden administration and Congress seek to expand the power system to accommodate renewable energy such as wind and solar. The rising demand for power for electric vehicles also increases the urgency of securing the grid from attack.

FERC announced at its December meeting last week it would direct a key industry standards-setting body to analyze whether it should bolster regulations for protecting critical infrastructure. But federal authorities don’t have jurisdiction over local electrical substations and distribution lines, the type of equipment that was attacked in North Carolina.

“Are we going to have armed guards at every substation, every transformer in the country, in order to make sure this doesn’t happen?” FERC Commissioner Willie Phillips asked earlier this month, referring to the North Carolina attack. “Or [are these attacks] something that we can just expect more often?”

Even though utilities, federal agencies and state regulators have implemented measures to harden the grid over the past two decades, experts fear the system is more vulnerable than ever.

“If somebody really wanted … to create a blackout in a certain area to achieve whatever social, cultural, political objectives, it’s fairly easy to get access to that information right now — and the tools necessary to execute it are readily available,” said Jonathon Monken, who oversaw system resilience at PJM Interconnection, a power market covering 13 states. He is now a consultant at Converge Strategies.

Data analyzed by POLITICO showed that through August, utilities this year have reported at least 101 incidents they deemed to be intentional attacks, threats of an attack or vandalism on the utility’s system, according to a compilation of incidents that utilities reported to the Department of Energy. These attacks affected more than 22,000 customers, although the vast majority of instances resulted in no outages.

Utilities classified only four of those incidents — in Texas, Montana, Florida and Washington state — as related to cybersecurity. The totals also included suspicious activities.

The DOE data does not publicly provide details on any of the attacks, including how they were carried out or whether any suspected perpetrators were arrested. DOE itself receives a more detailed accounting of these reports from utilities, according to a senior DOE official, which can range from suspected drone surveillance to intentional gunfire. The department authorized the official to speak to POLITICO on condition that the person not be publicly identified.

Federal regulations require utilities to report any disruption to some portion of the power system, Monken said, but reporting requirements for incidents that don’t necessarily cause a disturbance are less clear.

One example of an incident that falls into that reporting gray area was another shooting at a Duke Energy hydropower facility in South Carolina on Dec. 7, just days after the substation shootings in North Carolina.

CBS News reported that company employees saw someone opening fire with a long gun at the Wateree Hydro Station in Ridgeway before speeding off in a truck. That incident did not disrupt the power supply. A representative for Duke Energy did not respond to multiple requests for comment on whether the utility filed a report on either of December incidents.

“The language is more clear when physical security systems are actively targeted as a mandatory report versus a utility assessment that it was random vandalism that was not intended to disrupt service,” Monken said. “To some degree the ambiguity is intentional because all scenarios cannot be accounted for, and DOE wants to avoid reporting overload that would just create a lot of ‘white noise’ that could obscure meaningful intelligence collection.”

The senior DOE official said that the agency is most interested in quickly reporting incidents that have the potential to cause immediate disruptions, but is also interested in aggregating all incidents, including those that don’t rise to a high level of threat. The official also said utilities sometimes have to make “judgment calls” related to smaller-profile incidents that don’t disrupt its daily operations.

“Generally, the electricity sector in particular is very cognizant of security … and they are very open to sharing information,” the official said. “And so we do see that they generally share more things out of an abundance of caution, which is encouraged.”

That also means the number of threats to the grid may be even higher than DOE’s data reflects.

According to POLITICO’s analysis of the DOE data, the number of physical or cyber attacks or threats reported through August of this year is nearly 70 percent higher than the 60 reported in the same period last year.

Last year saw a total of 97 reported attacks, including seven cyberattacks, according to the DOE data. Those followed a total of 96 attacks in 2020 and 81 in 2019.

Overall, the past three years have been the most active for reported attacks on the grid in the past decade, after the incidents had dipped to a low of 42 in 2015.

While authorities don’t know the motivation for the North Carolina substation attacks, they said the perpetrators shot at the substations intending to cause widespread outages. And signs exist that the grid is becoming a target for at least some domestic extremists. In February, three white supremacists pleaded guilty to a plot to shut down parts of the nation’s power system to sow unrest and cause a “race war.” Four neo-Nazis in North Carolina were charged last year with a similar conspiracy in which authorities said they aimed to take down a critical substation with guns and explosives.

A senior official at the nonprofit North American Electric Reliability Corp., which sets reliability standards for utilities and reporting rules on outage incidents, told FERC during a supply chain security conference hosted by the agency that this year has seen “a steady uptick” in physical attacks on the grid.

Some incidents have been less disruptive — vandalism or robbery for instance. But Manny Cancel, who heads NERC’s Electricity Information Sharing and Analysis Center, told FERC that there has also been “a significant amount of ballistic gunfire damage” in some parts of the country.

NERC does not provide data on specific security events, and publicly available DOE data does not detail which incidents included gunfire. But many of the attacks in the data reported to DOE included either a “physical attack,” “physical threat” or “actual damage” to some power system facilities.

Federal regulations dictating how utilities bolster their systems against attacks mostly focus on major substations and transformers — the kinds of critical components that DOE and FERC have warned could lead to widespread outages if attacked in a coordinated way.

Facilities that could contribute to that kind of extensive regional catastrophe have strict security requirements that include a range of protective measures, such as armed security staff, bullet-resistant fencing or video monitoring. But smaller, local or rural facilities — such as the pair targeted in Moore County — often don’t meet the criteria for that level of security. Instead, those substations are subject to state or local regulations.

In a statement, an Energy Department spokesperson said the agency “takes the security of the nation’s power grid very seriously and will continue to work with law enforcement, interagency partners, and utilities to address any and all interruptions of electric power and threats to our electric system reliability.”

FERC spokesperson Mary O’Driscoll said in an email that the agency “continues to closely monitor all developments and is coordinating with federal and state agency partners” and NERC.

“The security and reliability of the nation’s electric grid remain our top priorities,” O’Driscoll said.

The Edison Electric Institute, a trade group of investor-owned utilities, did not respond to a request for comment on the trend of rising grid attacks.

Meanwhile, the number of critical grid components vulnerable to attack will only grow as the U.S. expands the power grid over the coming decades and as more people and businesses buy electric vehicles. Wind and solar power plants in particular are often in remote areas where fewer grid protections may exist — and they offer more entry points for attack than a single power plant.

“With more and more [distributed energy resources] going up, … there’s going to be an issue of additional transmission, say, that creates additional vulnerabilities,” said Emile Thompson, who chairs the D.C. Public Service Commission and serves as co-chair of a joint state utility regulators’ committee on critical infrastructure.

“And then, of course, those assets themselves are vulnerable,” he said. “And so how do you ensure that a solar field in the middle of the country is adequately protected? Same issue you would have with some type of power plant, but now you just have many more smaller assets.”

[flexi-common-toolbar] [flexi-form class=”flexi_form_style” title=”Submit to Flexi” name=”my_form” ajax=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”post_title” class=”fl-input” title=”Title” value=”” required=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”category” title=”Select category”][flexi-form-tag type=”tag” title=”Insert tag”][flexi-form-tag type=”article” class=”fl-textarea” title=”Description” ][flexi-form-tag type=”file” title=”Select file” required=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”submit” name=”submit” value=”Submit Now”] [/flexi-form]