Jimmy Choi’s TikTok page is filled with the typical videos of a high-level athlete: clips of himself doing one-armed pushups, climbing ropes, holding planks with weights on his back. If you look closely, though, you’ll notice that even before he begins his feats of strength and endurance, his hands are shaking. Choi has Parkinson’s disease, a central nervous system disorder that causes tremors, and he often posts about what it’s like to live with the disease.

“People see the stuff that I post and they’re things that most average people can’t do,” Choi says. “I often show the other side of things, things that I struggle with on a daily basis.” He makes air quotes as he talks about the things “normal” people do easily — tying shoes, buttoning shirts, picking up pills — that he has trouble with.

One of his daily struggles comes in the shape of the pills he takes to manage his tremors. They’re very tiny, making them difficult to grasp with trembling hands. In late December, he posted a video showing his struggle to grab a pill from a container. That video set off a domino effect, inspiring designers, engineers, and hobbyists across TikTok to craft a better pill bottle for people with tremors or other motor disorders.

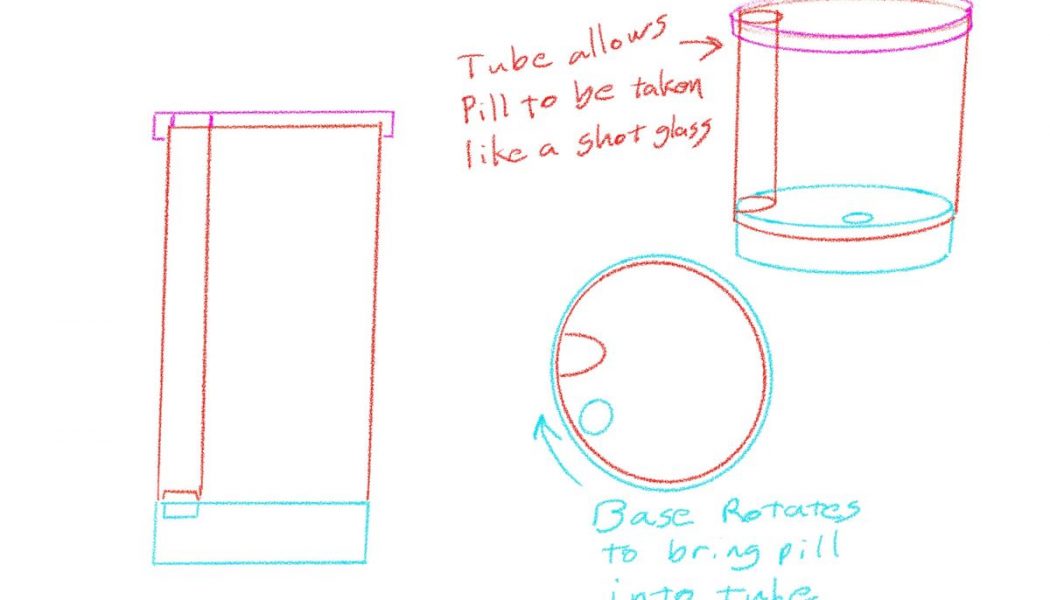

The video made its way to the For You page of Brian Alldridge, a videographer whose page had, until then, mostly consisted of Snapple facts. Though he had no prior product design experience, Choi’s problem struck him so much that he almost immediately set out to fix it. He started sketching designs for a 3D-printable bottle that would remove the need to dig for an individual pill.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22253184/IMG_0282.jpeg)

Alldridge has graphic design experience, but he had never tried making a 3D-printable object before. So he started learning Fusion 360 3D modeling software, and a few days after seeing Choi’s video, Alldridge posted a TikTok with a design for a more accessible pill bottle. The design features a rotating base that isolates a single pill, which can then be dispensed through a chute to a small opening at the top.

Because he doesn’t have a 3D printer himself, Alldridge put out a call on TikTok seeking someone to try printing his design. That’s when things started to snowball in a way neither he nor Choi could have anticipated. Alldridge woke up the next day to find that his video had thousands of views, and an overwhelming number of people wanted to print the bottle. He says he panicked, thinking to himself, “Oh no, this is bad, what if it doesn’t work.” And it didn’t. The base didn’t turn, the pieces wouldn’t snap together.

But the 3D printmakers of TikTok had already latched on to the idea. One of them, Antony Sanderson, printed a copy and stayed up for hours sanding down the pieces to get the bottle to work. Once it was proven that the design had potential, others joined in to fine-tune it — fixing up the printing problems, adding a quarter turn, and making it spillproof. The design is now up to version 5.0, and while some people are continuing to make tweaks, it’s ready for use and distribution.

People sometimes get so swept up in the excitement of making a thing to help disabled people that they forget to actually consult with any. “As disabled people, we are used to frequently being designed for, not designed with,” says Poppy Greenfield, an accessibility consultant with Open Style Lab. But the team involved in the making of the bottle have been in contact with Choi throughout the process, sending him each prototype and asking for feedback.

Choi has been excited about the device from the very first version. He’s found that it not only cuts down the amount of time it takes him to grab a pill, but also significantly reduces the frustration and anxiety that usually come with it. Stress makes the symptoms of Parkinson’s worse, but with this bottle, “the anxiety level goes away,” he says. “The time it takes, and your risk of spilling these pills out on the floor in public, it’s almost zero.”

David Exler, a mechanical engineer, began sending bottles out to other people. He started a fundraising push through TikTok to raise money for the Michael J. Fox Foundation: when someone orders a bottle on Etsy for $5, he sends that money to the foundation. So far, he’s reached his initial goal of 50 bottles, and he plans to continue donating as he prints and sends more. He just bought a second 3D printer to keep up with demand, and he’s been using part of his stimulus check to fund printing and shipping.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22253205/IMG_3012.jpg)

While Exler, Sanderson, and others continue printing the bottles, Alldridge is working on patenting his original design and pursuing mass production. He plans to release the 3D-printable version into the public domain and let nonprofits manufacture their own. Version 5.0, which is Exler’s derivation of Alldridge’s design, will remain available to anyone who wants to print it. “His creation of that patent doesn’t stop me or others from taking this model, making changes, sending it out to people who need it,” says Exler.

Alldridge is dismayed at people who have reached out to him with the intention to make money from the design. “The thing that really surprised me and continues to surprise me,” he says, “is the audacity of people to try and take something that’s been so community-driven and should be made so freely available, to outright show up and be like, ‘Hey we can make a lot of money on this.’” For everyone involved in the project, the point is to get bottles into the hands of people whose lives would be improved by it, at as little cost as possible.

Low costs are important for disabled people, who often encounter a “CripTax” on useful products and services that are prohibitively expensive and not covered by insurance. A collaborative process like this one, where anyone with a 3D printer can print and send the bottle to whoever needs it, “has the potential to minimise CripTax and put us on a level playing field,” says Greenfield.

Both Greenfield and Choi think the pill bottle project is a prime example of the good that can come out of social media. When it comes to community-driven projects for disabled people, “it can be hard to attract the attention of non-disabled designers,” says Greenfield. “I think TikTok does this in an enticing way, creating awareness and encouraging more community involvement through visually seeing the issue.”

Choi thinks the way videos spread on TikTok is something that’s particularly useful for disabled people whose struggles are typically overlooked. “We don’t have to wait for the knight on a horse to come save us, we can be our own advocates and we can make a difference on our own,” he says. In this case, his self-advocacy led to an idea that was crowdsourced into fruition in only a few days. That speed is exciting for Choi, who is used to hearing about Parkinson’s research and product development that take months or years to complete.

There’s a story Choi likes to tell about a marathon he ran a few years ago. He stopped at a water station to take his Parkinson’s medication. His tremors caused him to drop the pills on the ground. “People are stepping on these pills,” he says, “and I’m sitting there staring at five or six crushed pills on the floor and I’m thinking to myself, ‘do I want to lick them off the floor?’” He still had miles to go in the marathon, and he seriously considered crouching down to lick the stomped pills. “If I had a device like this back then, that wouldn’t have been a problem.”