A lonesome highway exit on a cool, black night. Orange lights blur in the rear-view mirror of an 18-wheel rig. His hands on the wheel, your hand in his lap. A romance as transient as a truck stop. That’s the image the mysterious masked singer Orville Peck conjures on “Drive Me Crazy,” a piano-led ballad dusted with the neo-country star’s reverberating, whiskey baritone, divulging a fantasy of two wanderers who find each other — and passion — on the road.

“It’s a trucker love song,” Peck describes, with a laugh. The track, he explains, was written while on a national tour following the March 2019 release of his debut album, Pony. The somber, self-produced breakout collection featured the up-tempo “Turn to Hate” and the hypnotic “Dead of Night.” His lyrics wove decadent tales of outlaws and outsiders (smalltown drag performers, in the case of “Queen of the Rodeo”) while his spaghetti western-inspired visuals often incorporated arresting homoerotic imagery: His “Hope to Die” video referenced the sexually charged illustrations of Jim French and, in one still, Peck appears framed by another man’s bare calves as he purrs about two young bandits on the run. The collection felt at home amidst a greater cultural discourse that called into question the hallmarks of country music — who it’s for and who can make it — that emerged in response to the conflicted reception of Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road,” which released around the same time. Its sleeper success propelled the singer from representation by the indie Sub Pop Records to a major label deal.

Now, backed by Columbia Records, “Drive Me Crazy” has found its way onto Peck’s first collection of new music in over a year, the EP Show Pony, which picks up confidently where Pony left off. “I really tried to write songs from a sincere place, because I think that’s how a country song, especially, should begin,” he says. “And then I usually try and take it from that point to something really bold.” That strategy is apparent in the collection’s six tracks, which slowly grind with grit and gloom, even when describing earnest hopefulness, and crescendo with some of his most accessible work to date. On the EP’s opening track, “Summertime,” for example, the heavy sound of low, lead guitar-plucking betrays the sunshiney lyrical themes of “biding your time and staying hopeful,” as Peck describes in a release, while its music video sees the leather-wearing lone cowboy morph into a literal bouquet. “I’ve tried to find this balance of sincerity and drama,” he says.

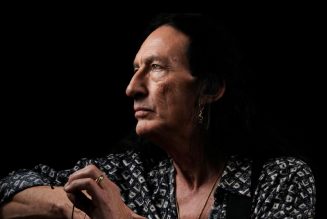

The same could be said for Peck’s characteristically old-school style. He appears like a Tom of Finland fashion illustration of the Marlboro Man, often wearing extravagant, brightly colored Nudie-esque suits, as on the May 2020 cover of Attitude, where he appeared opposite Diplo in a powder blue set decorated with embroidered images of handcuffs, whips, and nude cowboys. He is best associated with his signature mask: typically a black leather shroud sewn to a waterfall of fringe, with almond-shaped peepholes that reveal piercing blue eyes. He has over 30 pairs and mostly hand-stitches them himself; though, on one occasion, he appeared courtside at a Miami runway show, stationed beside Kim Kardashian in a Dior-monogrammed veil made custom by the Parisian atelier. On a recent Zoom call, he styles a simpler model (all black with the occasional silver rhinestone) with a cowhide-print vest, a monochromatic shirt unbuttoned just so, and a ten-gallon hat with a massive, upturned rim.

The trademark garment may resonate differently based on a viewer’s experience: What reads to one as an update on the Lone Ranger’s classic covering may seem to another to reference the visual language of kink, like a trimmed rendering of a gimp mask. The singer would welcome any speculation; after all, that’s play of wearing a disguise, the limitless projections of the imagination. “I think a lot of stuff these days is really spoon-fed for people, and I hate that,” he says. To that end, Peck won’t reveal much about his personal identity, but he does offer how his background among “DIY independent artists” has influenced his tendency towards subversion. He is also openly gay. “It’s totally drag,” as Peck describes his persona by comparison to another subversive art form. “I always say the country-western star that I aspire to be is a bit of a throwback to a time when you took who you were at your core and blew it up to the most over-the-top level… That’s exactly what a good drag performer is, as well. That’s the drag I love and that’s the artistry I love just across the board.”

Sarah Pfeiffer

Sarah PfeifferPerhaps that theatricality and aptitude for visual storytelling is what resonates so profoundly with Peck’s LGBTQ+ fanbase, in particular, who may feel as if their stories are being written into the genre for the first time in recent history. He likens “Drive Me Crazy” to the narrative ballads of classic country, invoking by name the late, great musical storytellers Tammy Wynette and Bobbie Gentry. He closes Show Pony with a cover of Gentry’s 1970 hit “Fancy,” a dark ballad with the twang of beat poetry that resurged in the ‘90s per a rock-and-roll makeover by Reba McEntire. “I can distinctly remember dancing around my bedroom with a hairbrush, singing all the words to ‘Fancy’ when I was 13 years old,” Peck recalls. Switching up the pronouns, Peck’s take, which he began performing live on tours (he also regularly sings Lana del Ray’s “Norman Fucking Rockwell”), is a sweltering chronicle of fetishization and gender fuckery, as the lyrics paint an image of the deep-voiced, tattooed crooner in a red, velvet-trimmed dress with a “split on the side clean up to my hips.”

Peck called upon the talent of another genre titan, Shania Twain, for his most approachable song yet, “Legends Never Die,” which brings Peck’s sound from the realm of Johnny Cash’s vintage murder ballads to the contemporary pop-country of big trucks and electric guitars. “I have loved Shania my whole life, being a country fan, being a gay kid,” he says. “Cut to a few months [ago], I’m sitting at her ranch in Las Vegas, feeding her horses and hanging out with her and just working on the song.” Peck, who first met Twain at the Grammys in January, wrote the duet with her in mind, and it tributes her icon status. In the visual, Twain appears in a leopard print jumpsuit with fringe bat wings and a glittering gold cowboy hat, an homage to the homemade outfit she wore in her “That Don’t Impress Me Much” music video circa 1997. “It’s still sinking in, to be honest,” he adds. “It’s a dream come true. I’m pinching myself every day about it.”

And though “Legends Never Die” may mark the highest production value of Peck’s music to date, his artistry continues to champion those on the margins. By drawing upon gay iconography in his visuals and lyrics, he seems to point out that these narratives have always existed. “There’s always been subversion in country,” he says. “I’m definitely not the first gay cowboy and I can almost bet I won’t be the last.” The man in the mask can be anyone and everyone — the truck stop lover, the honky-tonk heavyweight — and, as such, Peck hopes the themes at the heart of his work resonate universally. “Country music is about heartbreak, disappointment, loneliness,” he says. “There’s this idea that it’s for well-adjusted, law-abiding citizens, but country music was always about being an outlaw and being different.”