Of all the clichés about hip-hop we’ve endured over 50 years, the idea that hip-hop is the product of the streets — with all the attendant implications about what and who is and isn’t authentic — remains the most tiresome. In reality, hip-hop is largely the product of kids who stayed inside.

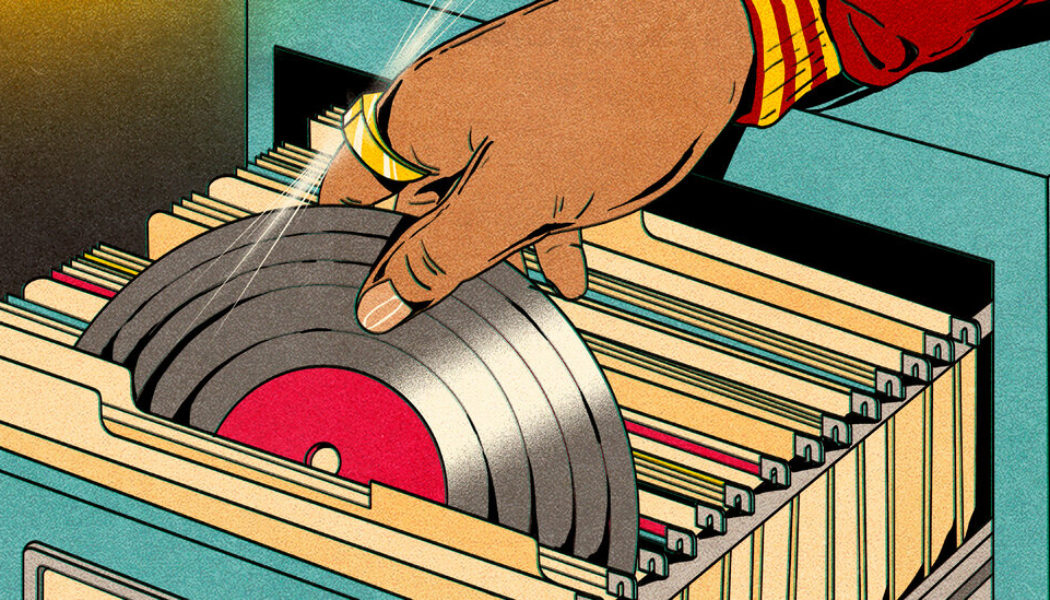

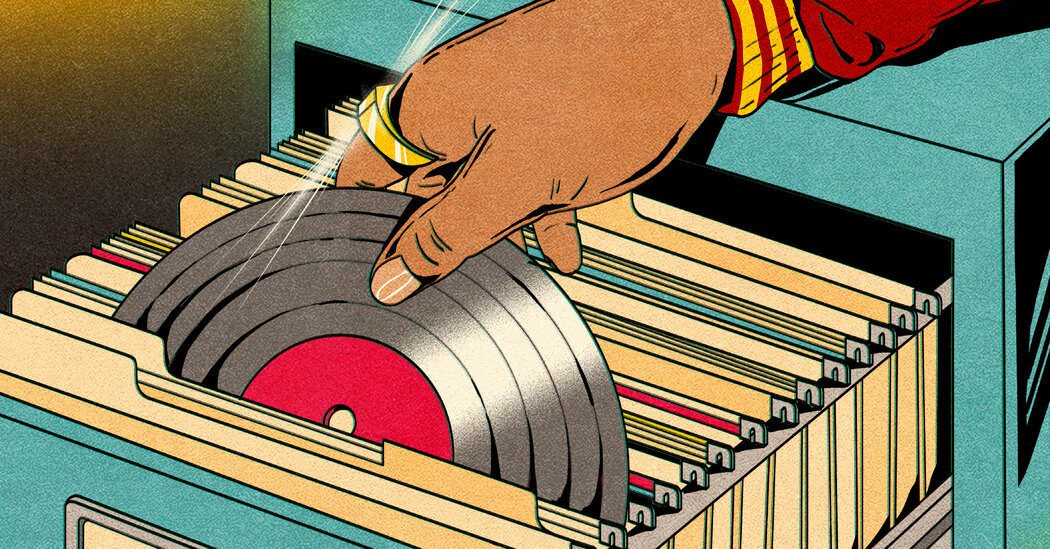

For five decades, beneath all the bluster and braggadocio, behind every park jam, party, stage show, flashy album cover or video, there were hours upon hours spent in a room, alone or with friends — amid dozens, sometimes hundreds, of records — experimenting, practicing, in spirited study.

The records are the key to it all. From the very beginning of the culture, the earliest rappers or M.C.s were there simply to point to the D.J.: Listen to what he’s doing. With two turntables and a mixer, the D.J. composed in real time — annotating, cross-referencing and building on a living library of specific beats and sounds that would become the foundation of hip-hop. That library would come to dominate the sound of pop music throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s; even now, musicians and producers remain its borrowers.

The records preserve the ethos of the world of the first hip-hop generation. They grew up in 1970s and ’80s New York, largely within African American families or those from the Caribbean. Records were treasured objects in their parents’ music-filled households, displayed with pride and handled with care.

That generation came of age just as the record achieved peak relevance, when D.J.s like Frankie Crocker had become high priests of popular culture, who drew their mystique and power from their access to specific records, both on the airwaves and in those temples of music, discotheques, a portmanteau, en français, literally meaning “record library.”

Is it any wonder that the new breed of D.J.s who created hip-hop — among them Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash, Afrika Bambaataa — became consummate collectors? Is it surprising that they would see records as more than just a medium for reproduction, that playing records meant actual play?

D.J.ing became sport, one that demanded records be touched in ways parents had forbidden; D.J.s used records as instruments, joining the musicians, manipulating their performances.

The sport, in turn, necessitated the hunt. Not for songs but for their constituent pieces: drum breaks that could be extended if one had two copies and two turntables (or else a cassette deck that could be paused), horn hits, snatches of vocals. Records remained precious, but not for the D.J.s’ parents’ reasons. Record store managers in New York City were mystified by the flood of kids looking for old vinyl rather than the latest releases.

As hip-hop compositions began to be released on records in the early 1980s, D.J.s became producers and beat makers, using new tools like multitrack recorders and digital samplers; now an entire song could be composed of prerecorded sound. The canon of break records grew into a vast, shared database, particularly via the work of uber-collectors like “Breakbeat Lou” Flores and Lenny Roberts, who created compilation albums of the hardest-to-find tracks. This series, “Ultimate Breaks and Beats,” was distributed to small record stores around the country and then the world; those nearly 200 songs became hip-hop’s common musical tongue.

You might not know that you know these records. You may never have heard of the Honeydrippers or their song “Impeach the President,” but its first two measures powered hits by Janet Jackson and Alanis Morissette. If you dug Hanson’s “MMMBop” or Justin Bieber’s “Die in Your Arms” or Travis Scott’s recent hit “HYAENA,” it’s because once upon a time, some D.J. excavated two copies of Melvin Bliss’s “Synthetic Substitution.” It’s telling that all of these fundamental break records were released 50 years ago, in 1973. The trace elements in hip-hop’s big bang still vibrate in our musical DNA.

The power of hip-hop, D.J. Rob Swift says, is that it accretes: Anything — songs, TV commercials, movies — can become a part of it, multiplying its power. The emergence of digital samplers precipitated a dramatic expansion in that collection. Crews like A Tribe Called Quest and producers like Prince Paul, Pete Rock and Premier widened the search for drums into a greater quest for harmonic and melodic material.

Parents’ record libraries — jazz, soul, rock, salsa — became more interesting. Mr. Swift recalls finding a record, Los Angeles Negros’ “El Rey y Yo,” in his Colombian immigrant father’s collection and realizing that his dad’s tastes had already been certified as hip-hop in songs by Biz Markie and KMD.

Hip-hop tracks retell parents’ and grandparents’ histories, their migrations both great and small. Each sample source recalls an ancestor; each song is a layer cake of historical reference, an orgasm of memory. When producers compose with a sample, they not only use its sonic information; they reminisce, tapping its meaning and numinosity — for them, for us, for the producers and artists who found it, for the musicians who made it.

The use of this break library in pop music has receded in recent years, in part because of our failure to create less complicated pathways for legal sampling, but you can still hear them now: a piece of the Brothers Johnson’s “Ain’t We Funkin’ Now” drives Harry Styles’s “Daydreaming,” and a tambourine originally from Lyn Collins’s “Think (About It)” shakes the K-pop act NewJeans’ single “Super Shy.” The persistence of hip-hop’s database is astonishing, as is how much meaning just a handful of initial sources still transmit.

One such example is the 1980s tape-edit records by Mantronix and Double Dee & Steinski. On a frantic mix called “Lesson 1,” Steve “Steinski” Stein, then a copywriter at Doyle Dane Bernbach, included a few seconds of Fiorello La Guardia, reading the funny papers on the radio from 1945: “Say children, what does it all mean?”

The phrase became hip-hop scripture, sampled in songs by De la Soul and Cypress Hill. But what did it all mean to Mr. Stein, who first laid that bit of code in? “He was the New York mayor,” says Mr. Stein. A piece of 1940s New York, frozen in time by a New Yorker in the ’80s as part of an underground New York musical culture, available still at the press of a pad to highlight a musical or lyrical point.

These shared volumes of microscopic sonic knowledge were what A Tribe Called Quest’s leader, Q-Tip, chose to celebrate on hip-hop’s 50th birthday, with a brief D.J. set on Instagram, from inside, among his records. He played not hip-hop’s hits but the breaks, an ecstatic scroll through the database. Toward the end, Tip landed on the last chord of a horn crescendo from “Ain’t We Funkin’ Now.” He drew the vinyl back, playing that short horn blast over and over. “Is there anything more hip-hop than this?!”

He knew we knew it, knew the memories of countless parties and mix tapes and songs that these breaks evoked. I remembered seeing Q-Tip in one of Tribe’s earliest performances, at a small club on the Lower East Side in late 1989 or early 1990. Hooded figures, they entered not to their first single but to the decelerated opening bars of a classic break record from nearly a decade earlier, “U.F.O.” by the band ESG. We didn’t know Tribe’s members’ names yet. We didn’t even have their first album. But we knew that sound and roared when they played it. They were telling us something.

We know that you know that we know exactly what this means.

Dan Charnas is the author of “Dilla Time” and a professor at New York University.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.