Oasis’ (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? means the world to me. For much of my early life, during the 1990s, I bordered upon homelessness — at one point, living with my family in a van. Without television or toys, my siblings and I mostly relied on books and a battery-powered radio for entertainment. On days when we tired of those, usually during the hot malaise of a Chicago summer, my brother, sister, and I dreamed of escaping the barren yet gang-riddled West Side to some safer place. We were Black, but worse yet we were poor. I didn’t find a semblance of financial stability until my early teens. That’s also when I found Oasis.

Just before my freshman year of high school, in 2005, I began watching a channel called The Tube. They aired British Alternative and Brit Pop acts from the ’90s, and within the first hour, the blaring sound of a jet launching roared from my television screen. The song, “Supersonic”, was from Oasis’ debut record, Definitely Maybe, and it perfectly distilled the oft-quoted maxim of the band’s sound: “The melody of The Beatles and the power of the Sex Pistols.” I immediately went in search of the album, only to find their sophomore effort, (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, in my local record store. I brought it home and played the CD to the point of skipping.

There’s nothing inherently relevant in Oasis’ second album that should speak to a Black kid living on the West Side of Chicago. At least not from a stereotypical standpoint. It’s a pure pop record, which on a superficial level concerns finding the person who might save you, the travails of rock ‘n’ roll stardom, and cannonballs slowly rolling down the hall. But in my tiny room, I heard a record that spoke directly, even if unconsciously, to the urban Black experience. I listened to songs about defiance, distrust of an apathetic authority, and the kind of melancholy that so often mixes with joy. That album, now celebrating its 25th anniversary, still speaks as loudly today to that Black kid as it did to a Brit living through the post-Thatcher era.

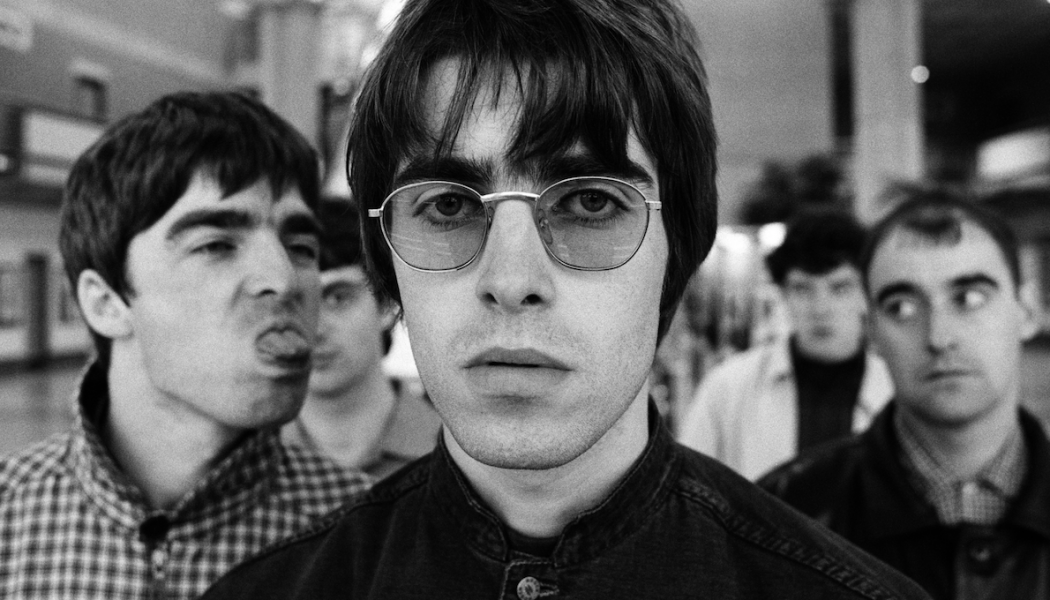

Much like myself, rhythm guitarist Paul “Bonehead” Arthurs, bassist Paul McGuigan, and the swaggering, tempestuous Gallagher brothers — Noel and Liam — grew up disadvantaged. Lead singer Liam and songwriter-guitarist Noel were raised Irish Catholic during the 1970s and ’80s. They were poor and mirrored many of their generation by living on the dole (unemployment benefits). They dreamt of fast cars, women, and drugs while living on council estates of Manchester. And while the term “council estate” might sound prissy, in America they’d be known as the projects. Rather than despair, the band proudly proclaimed themselves the next big British act. You can see why a Black kid might easily gravitate toward a group whose upbringing and swagger wasn’t too dissimilar to hip-hop artists.

Because Oasis originated from Northern England, they were adversely affected by Thatcherism, which called for free markets and a small state. The policies led to union busting and a steep decline in the economy’s industrial sector, which economically paralyzed Northern England. Many in the Oasis generation felt left behind: financially, educationally, and politically. For instance, census data reports the unemployment rate in Manchester during the early ’90s registering at over 24%, far exceeding Britain’s overall unemployment rate, which tracked at just over 12%. In response, bands like The Smiths became defiant forces during the 1980’s and influenced later ’90s alternative acts like Oasis. The conversations that The Queen Is Dead began continued on Oasis’ raw debut, Definitely Maybe, a record translating everyday class toil into a plea for rock ‘n’ roll superstardom. As Alex Niven explains in the Definitely Maybe 33 ⅓, “Movingly and articulately, Noel Gallagher provides an evocative stream of metaphors that rack up to demolish Britpop cliché and reveal the sheer macabre nightmare of the psychological wasteland of the Thatcher years.” Such strengths translated to their next release.

Their second album, recorded at Rockfield Studios — where rock music royalty like Queen made “Bohemian Rhapsody” — would, for the briefest of moments, vault Oasis into being the biggest band in the world. While (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? might sound less punk, with regards to Noel’s unconscious commentary on Northern life during the post-Thatcher recovery, it instead matched a still-present discontent with an unbridled euphoria for the future.

Consider the album’s second track, “Roll with It”. Beneath the bouncy, shimmering guitars lurks lyrics not just about individuality — and the punch-the-air optimism that everything will be alright — but a call of defiance. “Don’t ever stand aside/ Don’t ever be denied/ Don’t let anybody get in your way, ’cause it’s all too much for me to take,” Liam snarls. Other songs like the piercingly psychedelic “Hey Now”, which diagrammed the band’s struggle with stardom, and the melancholy acoustic ballad “Cast No Shadow”, a tune emblematic of the warring brothers’ symbiotic vocal harmonies, also drip with the disaffection caused by Thatcherism. Tellingly, and brilliantly, Liam often changed the lyrics to “Cast No Shadow” during gigs from “As they took his soul, they stole his pride” to “You can take my soul, don’t take my pride.” While the former recounts a man whittled down to nothing, not uncommon for those living under oppressive circumstances, the alteration hints at not just defiance, but survival.

Yet, it’s Oasis’ signature tune (not “Wonderwall” … we’ll talk about that later), “Some Might Say”, which fully demonstrates how Noel’s keen ear for melody and Liam’s provocative vocals combined to explain the ways their generation remembered the harsh past but still clung to an undiminished hope for the future. Noel accomplishes this first through the causal verses — “sunshine” follows “thunder,” and if “heaven” exists, then so might “hell” — then following them with a chorus teeming with critiques regarding education and the cyclical failure of safety nets: “You’ve made no preparation for my reputation once again.” The dirty, swaggering guitars and forcefulness of Liam’s patented John Lydon-inspired snarl emphasize the assuredness of the phrase “brighter day” over the uncertainty of “some might say.” That was the magic of Oasis. Their music could comment upon white male angst, yet universally speak to a poor African-American kid.

That mixture of melancholy and euphoria is why the band’s music resonates 25 years later with a new generation. For example, following years as a stadium sing-along during football matches, the Noel-sung “Don’t Look Back in Anger” became an anthem of perseverance after the Manchester Arena bombing, an event leading to the deaths of 22 Ariana Grande concert-goers. Consider the prototypical, older male Oasis fan in comparison to Grande’s teenage female fanbase. Or how about the guitar-driven indie tenants of the Britpop outfit’s music in relation to Grande’s contemporary dance-infused tracks. The two generations should share zero commonalities, and yet the wispy melody, and Noel’s nonsensical lyrics, echoed to both during tragedy. Noel’s penchant for nestling beauty in the mundane through evocative wordplay elicits such camaraderie. And through his mysterious heroine, “Sally,” a personification for the innocence that departs with age and heartbreak, he further imbues, as the strings swoon beneath the restful bass run, the track’s bittersweet quality.

While the sprawling “Champagne Supernova”, a superior song in many respects, also warned of aging into the oblivion of the uncool, it’s “Wonderwall” that still garners the most spins. A perfectly written acoustic ballad that’s the favorite of every beginner guitarist, part-time karaoke aficionado, busker, and anyone who can sing half-in-key, the pop song’s hold remains so strong it’s approaching one billion streams on Spotify. A distinction not associated with other ’90s British hits, such as Radiohead’s “Creep” or The Verve’s “Bittersweet Symphony”. It might not be their best song, and yet, for a kid coming from homelessness in an at-risk neighborhood, the concept of someone finding me and saving me still feels powerful. I can remember how I longed for escape from that van. And whenever I hear the track’s strong back beat, almost-reggae-inspired rhythm, and Liam’s voice oxymoronically vacillating into soaring-flatness, I’m healed from those days.

And as the world has seemingly grown bleaker, unraveling with each Presidential debate or day without a COVID-19 vaccine, the belief that it’ll somehow be okay holds me warmly even as we enter an uncertain autumn. I think back on the incoherent music video to “Wonderwall”, which ends with five giddy men knowing in the span of a pop song that the ideas of their generation had conquered the world, and how powerful such an assurance would feel today. “Wonderwall”, like much of (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, resonates because of how it articulates the pain of different eras. The economic despair during Thatcher’s rule and the distrust of her rules isn’t too dissimilar to the way portions of America feel under Trump. I identified with the same hardship even as a Black teen during the latter stages of the Bush presidency.

The cruel irony of Oasis’ ability to connect across experiences and decades is the present disconnected relationship of the two estranged brothers and the ways they separately changed. When the Leader of the Opposition, Labor Leader John Smith, passed in 1994, the band fell hard for his replacement Tony Blair. As Niven explains, “For someone like Noel Gallagher, Blair was merely another man like John Smith, a man poised to finally unleash the anger and yearning of the ’80s by seizing power and doing it for us.” But Noel would be duped by New Labour, which was merely Thatcher Conservatism in sheep’s clothing. The band and Noel would never truly recover their working-class bonafides afterwards, especially as their music began to veer from the shared community euphoria of their earlier records into the extravagant coke-fueled Be Here Now and their later entrenchment into self-aggrandizing their wealth.

But to my ears, before their unforgivable stumbles, (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? remains large and sweeping, yet an intimate failsafe. I still have the now-worn-down CD (signed by Noel Gallagher at a concert a few years back) in my collection, and with each Spotify play, not only am I reminded of how much comfort the words and melodies bring forth, today and yesterday, but I’m filled with the same hope for tomorrow that Brits in 1995 felt. And right now, we could do with a little hope.

—

Pick up a copy of (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? here…