LOS ANGELES — “Imagine yourself young.”

When I first heard Karate’s Geoff Farina sing that line in 1997, I was still on the edge of 18, imagining myself even younger. Now Farina was back in my life, singing his magic words at the Numero 20 festival in Los Angeles on Saturday night, transposing the weekend’s fundamental proposition into melody.

Organized by the reissue label Numero Group in self-celebration of its 20th anniversary, this wasn’t a festival of reunited bands so much as the reunification of a scene — a loose coterie of sophisticated post-hardcore groups who mostly (barely) left their respective marks in the mid-’90s. For me, the whole thing felt almost too weird to be real, as if the most niche slice of my high school CD collection had been resurrected into sentience. Imagining myself young at Numero 20 would not be a problem. But imagining how I’d feel on the other side of it all was something else entirely.

Nostalgia can feel repulsive until it’s your own. With our communal digital existence perpetually forcing us to live alongside so many other people’s memories, it’s easy to feel alienated by the present we all share. Plus, listening to someone brag about their most obscure teen faves might be worse than listening to them read from their dream journal. Should we blame social media or the Pixies? Rock-and-roll memory cults have run rampant since that portentous reformation nearly 20 years ago, making the Pixies’ initial seven-year run from 1986 to 1993 look like a funny blip of prophecy. Since then, nearly every overlooked, underloved rock group seems to have reunited by fate, fancy or reflex — meaning that it’s only a matter of time before some nostalgia-fluent impresario marshals a handful of half-forgotten, totally formative bands from your adolescence (say, Karate, Chisel, Unwound, Ida, Tsunami, Rex), onto the same 21st-century ticket stub.

So when I stepped into the Palace Theatre in downtown Los Angeles on Saturday evening, I could feel my brain toggling between punky skepticism and happy anticipation. But beneath that, I sensed a darker churn — my general midlife worries sloshing around in a more visceral paranoia over the fate of the species. In the grander scheme, I know how nostalgia can be a lazy U-turn back down a psychic dead end; how, personally, it can amount to a failure of imagination; and how, in today’s society, it feels directly linked to our collective retreat from the ecological danger on the horizon. Didn’t the hardcore-punk ethos that these Numero 20 bands once burned into our teenage psyches teach us to never retreat?

Already imagining myself young, I tried to broaden my 43-year-old mind. I tried to imagine my older self imagining me, right now, attending this music festival. Is that what the future looks like? Memories of memories of memories? Listening to this twinkling, indelible Karate song, I could feel my nostalgia bouncing back and forth between a set of infinity mirrors. I wanted it to hold still, but, like the music, it refused.

So I grasped for something quantifiable and started counting band members. Turns out, more than a few groups at Numero 20 weren’t sweating historical accuracy. The DIY indie troupe Tsunami had grown in size (two drummers, multiple guitarists) to accommodate the changing membership of its original go-round, producing a firmer, more forceful sound in the process. Meantime, the New York group Ida stretched itself wide enough to contain two generations of players (guitarist Storey Littleton is the child of Ida co-founders Elizabeth Mitchell and Daniel Littleton), and that elasticity generated an exquisite profusion of melodic detail. Instead of reruns, both bands felt like accumulations, their old songs thick with new truths.

The festival’s other big memory-smudge was out in the crowd where young attendees were outnumbered by their elders, but maybe only 3 to 1 — a division that felt most acute when the youngest ears in the house pressed toward the stage for Codeine, a band best known for making its tremendous slowness feel stark and colossal. During a fittingly leaden rendition of “Cave-In” — in which bandleader Stephen Immerwahr aptly sang, “These things take so long” — a curly-coifed teen at the edge of the stage could be seen headbanging with deliberation and vigor, which might have looked hilarious if it didn’t feel so profound. There’s a prevailing idea that the most stylish members of today’s youth are obsessed with retrieving the lost ’90s, but let’s not forget that they’ve grown up in an over-connected century in which boredom no longer seems to exist. My guess is that the Codeine kids at Numero 20 didn’t come to commune with the past so much as slow down the present.

That untenable speed-of-life is an all-ages affliction, though. In her extraordinary 2001 book “The Future of Nostalgia,” the scholar Svetlana Boym describes nostalgia as “a defense mechanism against the accelerated rhythm of change,” explaining the phenomenon as a countervailing emotional response to rapid industrial progress, positing nostalgia as a dominant mood in the 20th century while forecasting its exponential intensification in the moil of the internet age.

And now, with nostalgia permeating nearly every aspect of contemporary pop culture, most of our lingering suspicions over rock-and-roll reunions tend to sound like vestigial grousing. Are we skeptical of these bands making money? No, they don’t need to suffer for their art twice. Are we skeptical of them being separated from the heat of their original moment? No, they’re better at their instruments now. Are we skeptical of all the young people sitting near us, still sore that we were too broke to catch Unwound that one time in 1999? No, we are not allowed to hoard secret favorites at midlife. In fact, it’s likely that any band people currently care about is more popular than ever before, simply by virtue of the fact that there are more listeners inhabiting this planet — at least a half-billion of which subscribe to one streaming service or another.

Yet our nostalgia remains intimate, personal and fragile. It’s “a sentiment of loss and displacement,” as Boym writes, but ultimately “a romance with one’s own fantasy.” The displacement is from home, and the loss is of time, and I could feel that double-dream of homesickness and a time-sickness being funneled directly into my third ear at Numero 20 through the music of the Hated, a clamorous hardcore-punk band from the relative quiet of our shared hometown, Annapolis, Md.

Mutual stomping grounds, asynchronous timelines. Back in the mid-’80s, when the Hated were making astonishing teenage noise, I was still a little kid, attending elementary school birthday parties at the local roller skating rink where the band occasionally performed by night. Today, the Hated’s songs make me yearn for places I remember and moments I’ll never know, and onstage, their lyrics felt aimed at the center of my nostalgia-sodden being. “Echoes call you from your past,” went one gorgeously blustering song. “Words come back and haunt you someday,” went another.

Save it for the dream journal, right? Fine. But here’s something wild that happened outside of my head at Numero 20 during a set from Chisel, the D.C.-rooted trio led by singer-songwriter Ted Leo, later of the restless, semi-eponymous group Ted Leo and the Pharmacists. On Saturday night, Chisel’s mod-punk songs sounded as bright and sharply crafted as they did more than half my life ago, but when I headed into the aisles of the Palace Theatre to dance, my body betrayed me. I kept losing my balance. My arms shot around in unexpected directions. My hips forgot how swing and my shoulders picked up the slack a little too eagerly. Two left feet, two left clavicles, two left everything. What was happening?

My only conclusion is that our deepest musical nostalgia hides in our muscle memory. The last time I saw Chisel, back in April of 1997, I was a twitchy high school senior whose 10,000 hours of dancing in the nightlife were still years ahead of me — and here in Los Angeles, all of that grown-up, dance floor body-knowledge had somehow evaporated into the ceiling. As Chisel dashed through a zigzag performance of “The Unthinkable Is True,” at least five of my major muscle groups decided they were 17 years old.

Music tells our bodies the truth. Sometimes our brains pick up on it, too. And truth was, if you grew up on any of these bands, Numero 20 promised a reconnection with a certain era, but ultimately offered a reconnection to yourself — to your memories, to your musculature, to your community, to your potentiality. These bands probably conjured a sense of possibility within a younger version of you, and hearing them anew might have reopened those possibilities from the inside. Instead of a tomb, nostalgia became a trampoline — something you could jump onto with both feet, rebounding into an open future.

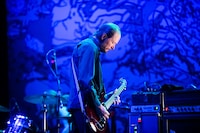

Or maybe our communal nostalgia at Numero 20 was more like a beating heart, pulsing and perpetual, forging continuity, pounding loudest during a performance from Unwound in which Sara Lund’s magnificent drumming seemed to circulate Justin Trosper’s blood-rushing guitar noise into every last corner of the theater. This music felt so loud, so vital, yet deeply interior, and by the time the band reached “Kantina,” a monumental song from 1993, an impossible question hovered over the stage: Did Unwound sound better in this moment than ever before?

Your answer didn’t need to be yes. It just needed to feel possible. And it did. And it stayed that way. The sound kept pouring out. Your blood stayed inside you. The past felt close. And the future felt big again.