This article originally appeared in the September 1995 issue of SPIN.

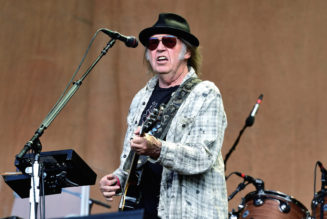

It’s getting harder and harder to remember that, for much of his career, Neil Young has been regarded—if loved—as a self-destructive oddball. Even in his most celebrated decade, the 1970s, he shelved entire albums; others, such as Time Fades Away and On the Beach, were so determinedly marginal that they’ve never been reissued on CD. Then, in the ’80s, he released a notorious series of rockabilly, synth-pop, and country experiments so off-putting that his label, Geffen, eventually sued him for not sounding like himself.

But starting with “Rockin in the Free World,” the anthem that bookends 1989’s Freedom, he went back to being Neil Young. Ragged Glory was a typically sprawling Crazy Horse album; Harvest Moon revisited the acoustic soundscapes of “Heart of Gold” with middle-aged wisdom. There were live albums, and MTV Unplugged cash-ins, yet the Young of the ’90s was cooler than ever, touring with Sonic Youth and devoting last year’s Sleeps With Angels to the memory of Kurt Cobain. For Mirror Ball, his newest album, he enlisted none other than Pearl Jam as his backing band.

So, as I prepared to meet Young, the questions I needed to ask seemed obvious: How had this apparent relic rebounded to become rock’s most enduring icon of survival? And were there lessons to be derived from his experience from which Cobain might have benefited, that Eddie Vedder and all the other mixed-up nouveau rock stars might yet still learn?

The problem is, Neil Young doesn’t answer questions like these. He just says, “Well, um, yeah. I guess. It’s hard to put things like that into words.” Or: “Answering the question is not nearly as interesting as reading it would be.” He tells you that he loves his life. It just so happens that in recent years he’s felt like doing the things everyone else wants him to do. Everything is “great.” A frustrated friend called me after interviewing Young for the New York Times. He had met numerous rock superstars, and none were so guarded. The best moment couldn’t even be used in a family newspaper.

As the Times photographer snapped his image, Young psyched himself into smiling by shouting, “Buy my album, motherfuckers!”

But what did we expect? This is the man who once rhymed “rock ‘n’ roll will never die” with “there’s more to the picture than meets the eye.” Not revealing the answers is his answer. He’s an asker, constructing his songs so that “there are no conclusions drawn.” Didn’t Cobain realize that “it’s better to burn out than to fade away,” the Young lyric that was also the dumbest line in his suicide note, isn’t a statement? It’s a question.

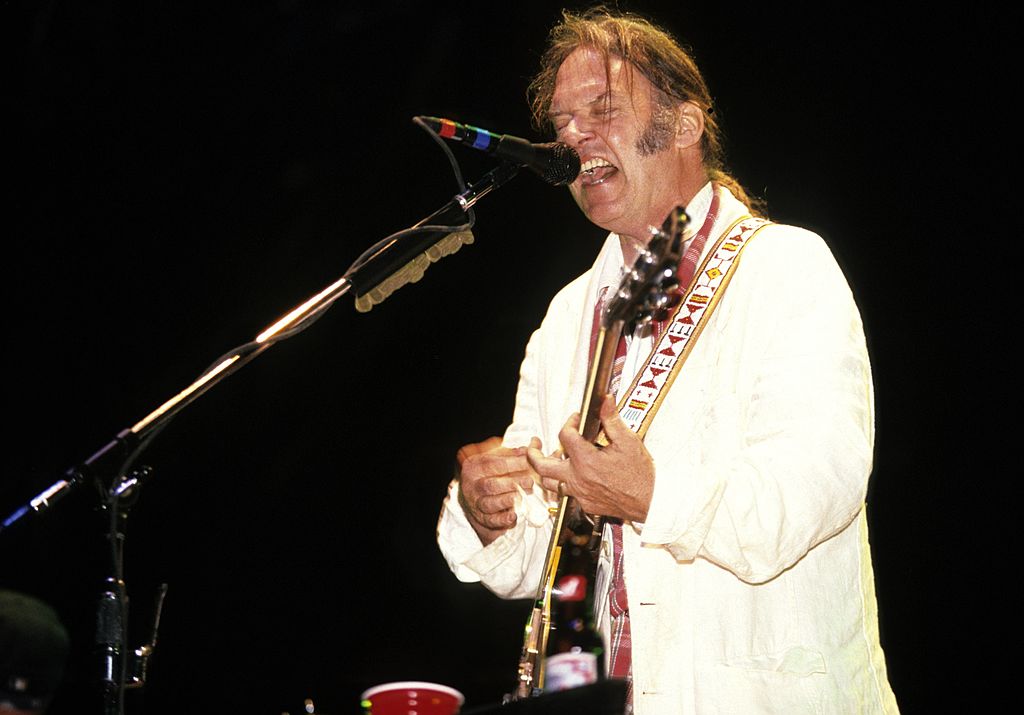

In November, Neil Young is going to turn 50. “But my amp still works,” he jokes as he drives me toward the beach in Half Moon Bay. Young’s long arms, frayed hair, and beefed-up body—he stays fit by exercising with a personal trainer, using the time he spends on the gym machines to choose between mixes of tracks for his albums—are only the finishing touches on his effortless dominance of every social setting.

Anyone granted permission to interview Neil Young in person begins by traveling south of San Francisco to the Mountain House Restaurant, located at Skyline Boulevard and Henrik Ibsen Road, in arty La Honda. He meets you there, under the redwoods; then if you insist on a little action, he’ll take you driving in one of his classic cars. This media cycle he’s favoring a 1956 Lincoln Continental Mark IV, with a battery acid scar along one side left by the betrayed lover of a previous owner.

Young eases into first gear as we head downhill. “What I’m really happy about, more than anything, is that I can play when I want to play, and to a great extent, I can play with who I want to play with.” The crucible of ’90s rock, which turns around taste and tribalism, doesn’t interest him. “If I was going to play with Crosby, Stills, and Nash, it wouldn’t be that big of a jump. I really like those guys, we’re in touch. Just like Pearl Jam. It’s nice to know those guys want to play with me—it’s like a gift. If I was going to tour with them”—in fact Young will do so in Europe this summer—”I don’t have to work at putting it together! Just take a couple of my guys. Great! Who could ask for more?”

Young and Pearl Jam’s kinship dates back several years. After Pearl Jam covered “Rockin’ in the Free World” on the Lollapalooza ’92 tour, Young invited the group to open for him during a stint in Europe. The friendship flourished further in 1994 when Pearl Jam played at the Bridge School Benefit that Young’s wife Pegi organizes annually; later that year, Young returned the favor by appearing with Pearl Jam at a Voters for Choice concert in Washington, D.C.

The new song they performed together that night, “Act of Love,” views the battle over abortion as a “holy war.” Inspired by the performance, Young suggested recording the song, and flew soon after to Seattle. He brought three more tunes as well: “Song X,” another rumination on abortion that deals with the murder of Dr. David Gunn; “Peace and Love,” an elegy for dead rock stars and dying rock dreams with some unfinished lyrics that Young asked Vedder to supply; and “Downtown,” a romping hippie fantasy of the ultimate club show.

All four tracks were recorded in just two days, with Pearl Jam producer Brendan O’Brien orchestrating the sessions. Recording in a new city, with all new people and an outside producer, was unprecedented for Young: for all his vaunted stylistic shifts he’s actually been a lot like Woody Allen over the years, picking from a set ensemble group of musicians, producing himself or using David Briggs. Still, with his Reprise contract up for renegotiation, Young had to realize on some level that an album with him backed by the world’s most popular rock band was worth taking a chance on. That’s the new Neil Young for you: Now his experiments feel like sureshots. (Young eventually signed a five-record deal with the label.)

Jazzed by how well things were going, Young started writing furiously back at his ranch. “I called back, and I said, ‘Well, you know, how about if we just get together for a day?’” He flew back up for what would be two more days of sessions that essentially completed the album. The first night, Young played with Pearl Jam at a special small concert held for the group’s fan club. “The audience enjoyed the generation thing,” he says. “We were rocking together, and it was real. Not like, here’s this guy we think is cool or the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame jam. When I play with them, they feel like my band.”

With the concert still in his ears, Young went back to his hotel room and wrote “I’m the Ocean,” Mirror Ball‘s most glorious tune, a summation and maybe a boast. “People my age / They don’t do the things I do,” he sings over a crinkled riff that repeats forever. He pledges love to his wife and family, voice quavering, then contemplates the baseball strike and O.J. Simpson. “They’re symptoms of social upheaval. America is really not ready for some sports hero to carve up a couple of people and for the baseball guys to not even play. The facts, they just keep piling up. And the ones that hit me hard enough end up in a song somewhere.” But the song moves past facts, as he marvels at our need for entertainment, violence, and myth. Young may hate the media flow of heroes and icons, but he also recognizes his contradictory compulsion to remain one of the giants, almost poking fun of himself for it. “I’m the ocean,” he ends the song chanting, “I’m the giant undertow.”

The only rock dinosaur ever to manifest an acutely bad conscience about it, the only avant-rocker ever to consistently tour stadiums, Young has an unerring ability to divine rock’s mythical core. He embraced the ’60s counterculture and ’70s singer-songwriter era with Buffalo Springfield, Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, and Harvest, then became as much of an alternative forefather as Big Star or the Velvet Underground with ’70s albums like Tonight’s the Night and the punk salute Rust Never Sleeps. As mainstream rock died in the ’80s, he stopped bothering with rock. When alternative rock started to become mainstream, he grew interested again.

Young’s music can be irritating, his guitar epics overblown, his eagerness to be a cultural spokesman overbearing. But then, the ocean has never been afraid of bigness. He can also be subtle and compact—”Don’t Cry No Tears,” “Winterlong, “Truth Be Known”—because he’s large in the only redeemable way: He contains multitudes. Where today’s rockers mumble and hedge, Young is incredibly sure of himself—then changes his mind. He loves deliberate contrasts: playing the same song twice on a single album, recasting the line “let’s go downtown,” so doomed and fatalistic on Tonight’s the Night, as a party anthem (with just a touch of the whirlpool) on Mirror Ball‘s “Downtown.” At a time when rock is an overly familiar force in our culture, Young’s honed ambiguities are one of the last enduring scraps of mystery we have left.

We’ve reached the real ocean now, by the crumbling cliffs of Half Moon Bay, and as we sit nuzzling Young’s three-year-old shepherd mix Bear, he tells me about some of his other projects. A Crazy Horse album (as opposed to a Neil Young and Crazy Horse album), for which he’s written two songs, is currently being recorded. A soundtrack for the Jim Jarmusch film Dead Man, which Young composed by improvising in real time—playing guitar, piano, and pump organ while watching the film on three separate occasions—should be released shortly. Our talk feels almost intimate, until the wrong question produces an “I don’t want to talk about that” delivered with the imperviousness of a man who’s spent half his life talking into tape recorders.

When Sleeps With Angels was released last summer, Reprise took out an ad in Billboard announcing that Neil Young would be doing no press interviews for the album—an oddly public way of staying private. Released just months after Cobain’s suicide, the album must have fallen into place almost as quickly as Mirror Ball. Hard to say, since Young is still keeping mum. Though his own work has long addressed the spectacle of death—”Ohio” was rushed out as a CSN&Y single within days of the Kent State shooting—he’s developed a Seattle attitude toward the press and commercializing grief.

“I’m not doing anything with that album. It stands on its own. That’s why I made the record. Too sensitive of a subject to isolate comments on. When you speak to someone who can write things down, you have to remember that they only write what they select. And it appears next to something that they can’t control, like an ad. And then that article can be quoted, and over time…l’ve seen the way things happen.”

When I ask if he could at least share how he’s navigated some of the pressures that ’90s artists have found so difficult, Young offers his odd ’80s albums as a parable. “I did a lot of records that were not popular commercial records, [but] they were the right records for me to make at the time.” He denounces commercialism and “media image slaves” as often as any dour grunge god, but his rhetoric is healthier, if no less airy. Purism in the face of profit isn’t the goal; “good music” is. Explaining his well-chronicled antipathy to digital recording (mollified somewhat on Mirror Ball with the introduction of a new technology called High Definition Compatible Digital), Young stresses, perhaps needlessly, “I’m a real freak for retaining the feel of the music.”

It’s only when talking about his musical ideals that Young is comfortable invoking Cobain. “How about ‘Drain You’ from the MTV New Year’s? Was that fucking nasty or what?” Young, who hates to listen to recorded music because it seems bland to him, made an exception and listened to tapes of Nirvana—he never saw the band live or met its leader. He dismisses Cobain’s attack on Pearl Jam as corporate sellouts: “That’s an immature comment by a guy who’s young, and trying to find his place, and a little confused. Because Pearl Jam is good. Why put ’em down? Just because they live in the same city and they’re both big bands? It’s pointless.”

But Young completely identifies with Cobain’s impulses toward intransigence and loner individuality. “I really could hear his music. There’s not that many absolutely real performers. In that sense, he was a gem. He was bothered by the fact that he would end up following schedules, have to go on when he didn’t feel like it, and be faking, and that would be very hard for him because of his commitment. The paradox of music is that it’s really meant to be played when you feel like playing it. It’s not meant to be played like a job. The purest essence of music is an expression, it should be done like a painter. You don’t paint when the audience comes in and pays their quarter. I don’t think he did a good job of dealing with it. But it’s understandable, considering how real he was.”

I ask Young about how he felt to learn that Cobain had quoted his lyric in the suicide note. Everything shuts down again. “I don’t want to talk about that. I can’t talk about that. I still sing the song. Now I remember him when I sing it.” Young hunches over the car wheel, using his elbows and forearms to steer the severe mountain curves with slashing strokes, working out the angst he’d refused to articulate.

Neil Young, godfather to the postpunks, lives like a hippie lord of the manor on a huge ranch named Broken Arrow, after the Buffalo Springfield song he wrote prior to his buying the place in 1970. It’s a real ranch, with a foreman named Larry, cattle herds, and trucks with Broken Arrow Ranch stamped on their side. But it’s also a children’s paradise, where peacocks step out into the middle of the road and llamas lounge on the grass. From the ridge Young has me drive to, you can see a canyon full of trees, a lake, several roads, and hills off into the distance. All his land. Another vantage point looks down toward the Pacific.

The ranch is Young’s “private place,” the symbol of the deeper stability that’s always underlain his restlessness. He’s been married to the same woman, Pegi, since 1978; they’ve got two children, the oldest of whom, Ben, now 16, has a severe case of cerebral palsy that renders him quadriplegic and unable to speak. (Zeke, an older child by actress Carrie Snodgress, has far milder cerebral palsy, and now works for a record company in Los Angeles. Neil and Pegi’s daughter Amber does not have the disease.) The effort to communicate with Ben was the subtext for 1982’s Trans, where the vocals are distorted by Vocoders, and a major reason Young spent the decade uninterested in “using the part of my communication skills” that makes his music accessible. We’ll never know if Ben is the real subject of the lyric on “Rockin’ in the Free World,” about a crack baby: “There’s one kid that will never go to school / Never get to fall in love / Never get to be cool.” And maybe we shouldn’t.

My direct question about how Neil and Ben now relate is rebuffed—”he’s just like any other kid. Sometimes he tunes you out”—but it’s clear that mom and dad have more than coped; they’ve made Ben integral to their lives. Pegi is chairperson of the board of the Bridge School, which brings together children with severe physical barriers to learning. The school’s success has led to plans to build a new campus on the grounds of an established private school; Young is excited about Bridge kids mixing with others—maybe that lyric won’t come true after all. Like any good native of Canada, he’s a hockey fan, with season tickets to the San Jose Sharks; Ben is his companion at the games.

Neil and Ben also share a love for model trains. Young designs electronic hardware that ensures that trains built by Lionel sound like trains. “My son and I can really enjoy these things together now because there’s all this feedback. It goes pretty loud. When he causes something to happen, he can really hear it. When he puts the brakes on and they squeal, and the thing stops, he knows, ‘Hey, I got brakes!’” I’m reminded of his hatred of digital recordings, for the passive sterility of the listening experience they generate.

On our brief excursion through a sliver of the ranch, we stop at the “barn” where Young and Crazy Horse recorded Ragged Glory and Sleeps With Angels. It’s a multi-room, comfortable space, with a small studio, an area to hang out, computers for record keeping, and a great back area for playing music, with a rear window overlooking the canyons. The barn is also a museum of sorts: all the ancient guitar amps Young has ever used are mounted along the walls of one room; dozens of tour jackets hang from the ceiling, nearby to an even larger collection of promotional baseball caps. Three members of Young’s technical crew are at work—they confer briefly with him about which of the giant trunk amplifiers from the Rust Never Sleeps tour should be sent to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which wants to put them on permanent display.

The folds of Young’s private life and past experiences give him more to mull over than most younger musicians will ever know. It takes a lot to move him at this point. Where everyone in alternative rock obsesses on music and culture, Young’s conversation is all but free of those sorts of references; he hasn’t heard the Hole album, for example, and actually refers to Kurt Cobain’s widow as “what’s her name?” “For me,” he says, “after playing music for 35 years or whatever, and going on all these tours, to keep it fresh I like to ration music.”

The biggest influence on Young’s music in recent years has been listening to the collected works of Neil Young, since he assembled what will eventually be released—now that High Definition Compatible Digital has solved the transferring problem—as a vast set of Neil Young archives. A “consumer” edition will include the best of the released and unreleased work, but he’s more deeply interested in the complete archive, which will document every session he ever did for collectors, in chronological order. “From the worst piece of shit to the best thing I ever did—you make the choice.” (I get a salivatory taste of things to come when I ask Young if he’s ever worked with female musicians and he mentions unreleased recordings with Joni Mitchell from the Tonight’s the Night sessions.) Hearing his music all over again seems to have reminded Young of who he was, and just in time. “Ragged Glory’ was the first album done after I listened to everything. Freedom, I’d listened to some of it.”

We’re leaving the ranch, and Young gets back in the car after fastening a gate with a sign that spells out “Private Property” in psychedelic lettering. “This could be a place where I got lost,” says Young. “All the things that I like to do are here. But that won’t happen because I’m too interested in what’s going on. I like to get out and see what’s happening, see people. More than listening to records, or listening to the radio, or tapes. The style of music, how in vogue, how cutting-edge it is, is not as important to me as how good it is. I’ve seen it happen for so long now that it really doesn’t make any difference to me what point in the cycle it’s at. I’m not immersed in the comings and goings of bands. I’m past that. I’m watching waves that are much bigger than those ones that people watch at age 19, 20. I did all those things with Buffalo Springfield—I was so focused, I knew all the groups. It feels like I’m just as into it now as I ever was, but with a different perspective.”

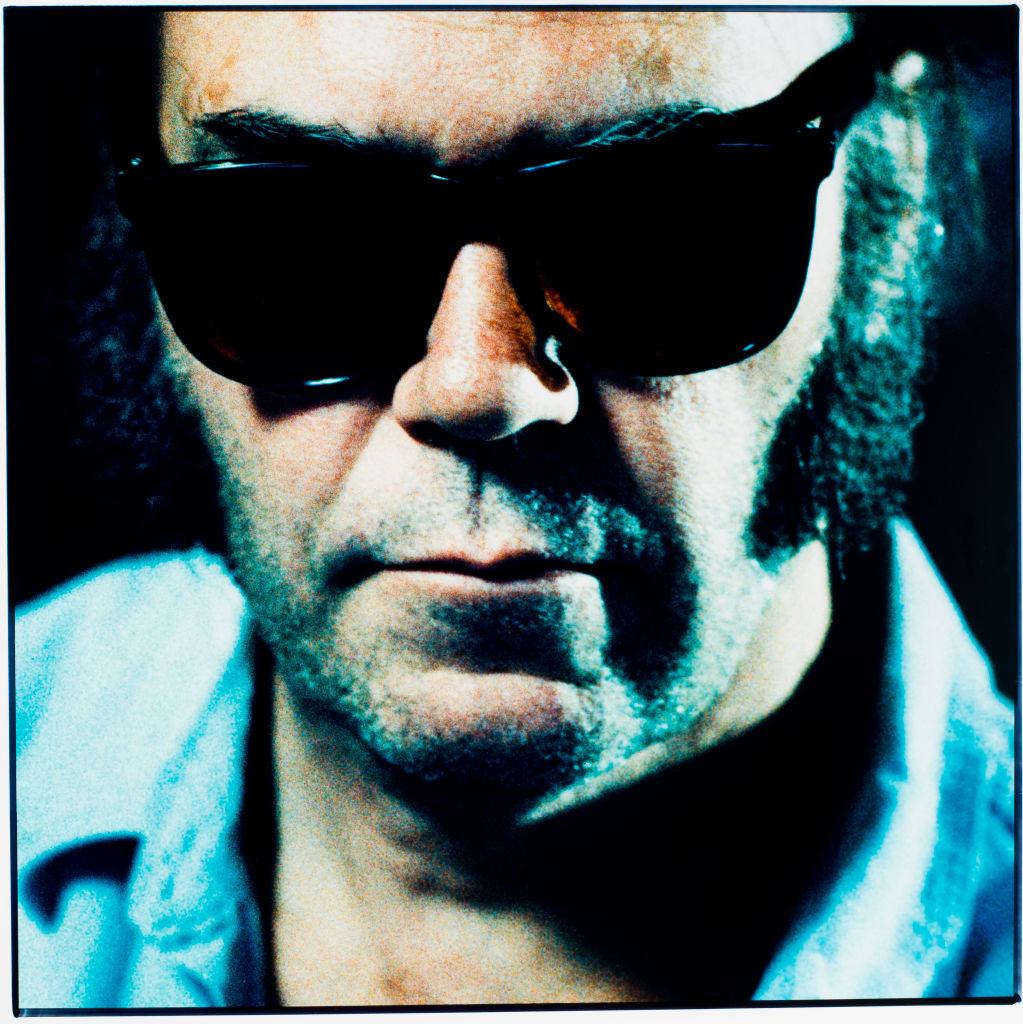

Earlier in our ride, a little frustrated with laconic answers, I’d accused Young of seeming awfully relaxed, and wondered how someone living on Broken Arrow could still have the violent side his best music has often tapped. He’s been simmering on that ever since, and now, our interview nearly complete, he puts a little spine into an answer. His eyes bore into me through tinted shades.

“You may not see the anger, or the angst, or whatever in me lay behind a song like ‘Powderfinger.’ But I’ve seen things in my life that I’ll never forget—and I see them every day. And I see strength that I can’t understand, and weaknesses that I can’t deal with. Watching my kids grow up—they go through all these things. All of it comes again, it just keeps happening, and you’re on the front lines; you watch them and there’s nothing you can do, you can’t tell them what to decide. You can see life going on. If you keep looking out, you can remain vital and vibrant in what you’re doing. That’s what I try to do with my life. Make it rewarding. No one wants to hear me go out and just not be there. That would be the worst thing I could ever fucking imagine. Just kind of going out and going through the motions.”

We drive back to the restaurant, where Kurt Loder and an MTV camera crew await. And, without any transition, Young immediately starts going through the motions of being Neil Young. Even his schmoozing is exaggerated beyond mortal levels; after our first interview, I’d been amazed at how quickly he went from talking about Cobain’s trouble with schedules to shaking the hand of the next journalist in line, bidding me a “see you next time!” farewell so impersonal he could have been addressing a stadium full of fans.

Now, every shallow Kurt Loder question gets a polite reply (though being asked to comment on the phenomena of body piercing was a little taxing). My favorite moment comes when Loder asked Young what he told people like Vedder who worry about selling out. “If the music is good and you run out of records, you sold out,” Young quips. “That’s what it’s always meant to me.”

Loder might have asked Young whether, by this logic, it’s selling out when you play a free show for your friends while leaving your fans parked forlornly outside. Up in Seattle on June 7, Young and Pearl Jam tried it this way, appearing unannounced at Moe’s for an audience of about 500 scenesters. Krist Novoselic and other glamor grungers were up on the reserved balcony, with garage rockers from the Fastbacks and Posies down in front alongside record store clerks and writers. They watched respectfully as Young and a Vedder-less Pearl Jam played all of Mirror Ball, with interminable versions of “Down by the River” and “Cortez the Killer” thrown in so Stone Gossard, Mike McCready, and Jeff Ament could live out every teen rock boy’s fantasy. The special evening proved to be shockingly ordinary. Cherry-picking an audience and removing all the tensions from live performances just isn’t the way to produce the legendary gig Young dreams about in “Downtown.”

Afterward, Young enthused to me about the attentiveness of the audience, which didn’t mind hearing so many unfamiliar songs. It reinforced, he said, his theory that “the ’90s is more like the ’60s than any other period has been as far as the bands and their audience relating to each other. During the ’60s, people didn’t scream out [the titles of] songs. They were listening to the fucking music.”

Well, maybe. But do we really want the ’60s back if it means hairy white guys rocking for rock’s sake? Young’s guitar solos, as always, managed to be crude enough to avoid sounding like a dinosaur cliché, but the Mirror Ball songs and the ancient warhorses didn’t always pull off the same trick: “Throw Your Hatred Down” is awfully corny, in precisely a ’60s way. I start to understand why Young has been telling every writer that Pearl Jam are “older than me. They’ve got old souls.” Who else could play with such unremitting earnestness? I left the club that night wondering if, possibly, Young had worked things out in his life a little too well.

Two and half weeks later, at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, Young changed my mind again. It was supposed to be a Pearl Jam show, a high point in the anti-Ticketmaster tour. Young was only slotted to play a little, unannounced, during the encore. But God must not care about service charges, because seven songs into Pearl Jam’s set a listless Eddie Vedder confirmed the latest—and last—tour disaster. He’d been stricken with a 3:00 A.M. stomach flu the night before and couldn’t continue. “Lucky for you,” Vedder said. “We got Neil Young.”

Suddenly it was the Seattle show all over, except now 50,000 people are hearing Mirror Ball unawares, instead of 500. Some of the songs, like “Act of Love,” sounded better in a big open field than they had overloading the nightclub PA. Only the crowd wasn’t ready to spend an afternoon concentrating on the unfamiliar. (Explain that ’60s = ’90s bit again?) Young and band cut down on Mirror Ball tunes, lengthened “Down by the River” and “Cortez the Killer” further, and added “Rockin’ in the Free World” to the list of oldies. Still, at the end of the set, after Jeff Ament came out to say that Pearl Jam would return at some later date, and Bill Graham Presents announcer Jerry Pompili asked the crowd to thank Young and Pearl Jam, boos far outnumbered cheers.

No one was demanding an encore—far from it—but Neil Young is always at his surreal best when you’re just about to throw up your hands and declare that rock is dead. He led the band back onstage and apologized halfheartedly for doing so many new tunes: “Sometimes I feel like a broken record doing all the old ones.” The next song was “Peace and Love.” In Seattle, Vedder, who’d been crouching invisibly in front of the stage for half the show, came onstage to reenact his only appearance on Mirror Ball. (“He knows when he’s involved it changes things,” Young told me.) In San Francisco, it was Young trying to recall and sing Vedder’s lines before an audience that didn’t exactly deserve a lyric such as “found love in the people.”

Young wasn’t through yet. “Here’s one I know you’ve heard before,” he said, and he and Pearl Jam burst into “Rockin’ In the Free World” for a second time. There’s always been an uncertainty about the song: Is Young making fun of rock or saluting it? On Freedom, he does two versions, one live before an uncomprehending audience, which only reinforces the doubts. Would the second San Francisco “Rockin’ in the Free World” be ironic, a sham lesson in concert etiquette? Of course not: It was the fiercest moment of either show, though scarcely anyone had remained to hear. Pearl Jam’s musicians looked dazed, and could barely keep up, but Young kept on rocking. That sounds corny—Young ought to be corny by now—but it wasn’t, and he isn’t. Corniness is just one side of what he has to avoid; a sulking hermeticism is the other. There’s a line in between, only sometimes it’s more like a fault line, a widening crevice. And that’s where Neil Young answers every question you might have. He plants one foot on either side, ignores the deeper complications, and holds everything together by blowing us away. •