A quarter of the deep links in The New York Times’ articles are now rotten, leading to completely inaccessible pages, according to a team of researchers from Harvard Law School, who worked with the Times’ digital team. They found that this problem affected over half of the articles containing links in the NYT’s catalog going back to 1996, illustrating the problem of link rot and how difficult it is for context to survive on the web.

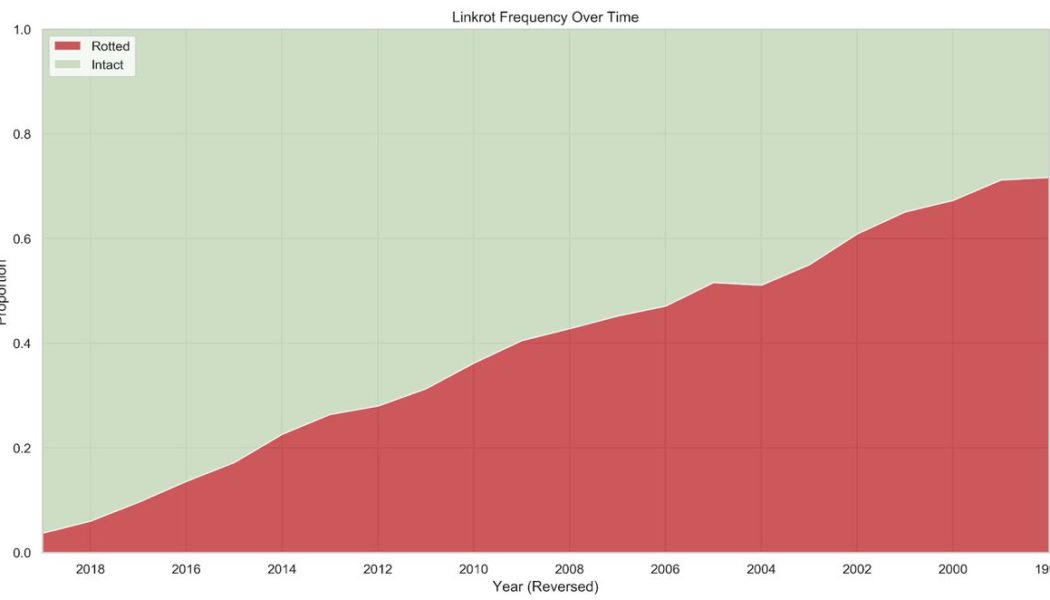

The study looked at over 550,000 articles, which contained over 2.2 million links to external websites. It found that 72 percent of those links were “deep,” or pointing to a specific page rather than a general website. Predictably, it found that, as time went on, links were more likely to be dead: 6 percent of links in 2018 articles were inaccessible, while a whopping 72 percent of links from 1998 were dead. For a recent, widespread example of link rot in practice, just look at what happened when Twitter banned Donald Trump: all of the articles that were embedded in his tweets were littered with gray boxes.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22531243/Linkrot_frequency_over_time.jpg)

The team chose The New York Times in part because the paper is known for its archiving practices, but it’s not suggesting the Times is all that unusual in its link rot problems. Rather, it’s using the paper of record as an example of a phenomenon that happens all across the internet. As time goes by, the websites that once provided valuable insight, important context, or proof of contentious claims through links will be bought and sold, or simply just stop existing, leaving the link to lead to an empty page — or worse.

BuzzFeed News reported in 2019 on the underground industry that exists where customers can pay marketers to find dead links in big outlets like the Times or the BBC and buy the domain for themselves. Then, they can do whatever they want with the link, like using it to advertise products or to host a message making fun of the article’s subject matter.

Link rot doesn’t just affect journalism, either. Imagine if Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up” video was deleted and reuploaded. There would be countless Reddit threads and tweet replies that would no longer make sense to future readers. Or imagine if you’re trying to display your NFT, and you discover that the source link now points to nowhere. What a nightmare!

There has been some work done in trying to preserve links. Wikipedia, for example, asks that contributors writing citations provide a link to a page’s archive on sites like the Wayback Machine if they think an article is likely to change. There’s also the Perma.cc project, which attempts to fix the issue of link rot in legal citations and academic journals by providing an archived version of the page, along with a link to the original source.

It’s unlikely, though, that the smattering of similar projects out there would be able to solve the issue for the entire internet, including social networks, or even just for journalists. Until we find a solution, articles will continue to lose more and more context as time goes on. As a perfect example: our article on link rot from 2012 has a source link to The Chesapeake Digital Preservation Group, which now leads to a 404 page.