On July 30th, a six-wheeled NASA rover the size of an SUV will embark on its journey to Mars — the beginning of a quest to decode the secrets of the Red Planet’s past. Equipped with a suite of instruments and a sophisticated drilling system, the rover is tasked with answering a question that has confounded scientists for centuries: has Mars ever hosted life?

The rover, named Perseverance, is one of NASA’s most ambitious planetary missions to date. Not only is the bot designed to analyze Martian rocks for signs of past life, but the rover will also cache dozens of samples to leave somewhere on the Martian surface. These samples will weather the next decade on Mars, awaiting the day that another robotic spacecraft arrives, picks them up, and blasts off. The samples will then travel back to our planet, where eager scientists will be waiting to receive them.

It’s all part of a herculean operation known as Mars Sample Return. The goal is to bring pristine pieces of Martian material back to Earth where we can study them in sophisticated labs. “If you want to confirm that life exists beyond the Earth, you probably cannot do it with any instruments that can be flown today,” Kenneth Farley, the project scientist for Perseverance and a professor at the California Institute of Technology, tells The Verge. “You really have to bring samples back to the lab.”

Perseverance is just the first — extremely complicated — step in that sample return process. If successful, Perseverance will neatly package dozens of samples of the Martian surface that may one day see Earth. They may tell us if life existed on Mars or if it’s always been a barren planet. “This is really a unique — really a once-in-a-lifetime — opportunity to get samples from a known location on Mars,” Tanja Bosak, a professor of geobiology at MIT who is a participating scientist on the mission, tells The Verge.

The search for life on Mars

In 1976, NASA sent two landers, called Viking 1 and Viking 2, to the Martian surface to actively look for signs of life. While the pair learned a great deal about Mars, they didn’t turn up any compelling evidence that life had ever existed on the planet, putting a damper on the search for a while. But in hindsight, the Viking landers were not well-equipped to answer that ultimate question. “Compared to what we know today, they did not have a very sophisticated understanding of how to actually look for life,” says Farley.

NASA followed up the Viking landers with orbiters that studied Mars from above as well as rovers that crawled across the planet’s surface. Over time, a new portrait of Mars’ past emerged. Thanks to data from these spacecraft, scientists realized that 3.5 billion years ago, liquid water lakes and rivers dotted the planet’s surface. Flowing water on Earth is perhaps the single most important ingredient for life on our planet; many scientists wondered if this lush Mars of the past hosted organisms, too.

Data from NASA’s most recent rover, Curiosity, reinvigorated the search for life. Dropped into a basin called Gale Crater in 2012, Curiosity’s instruments quickly determined that the region was once a giant lake. “At the same time as that environment existed, on Earth a similar environment would not only be habitable, it would have been inhabited,” Farley says. “There would have been living organisms in a very similar environment at a very similar time on Earth.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20534143/pia23239.jpg)

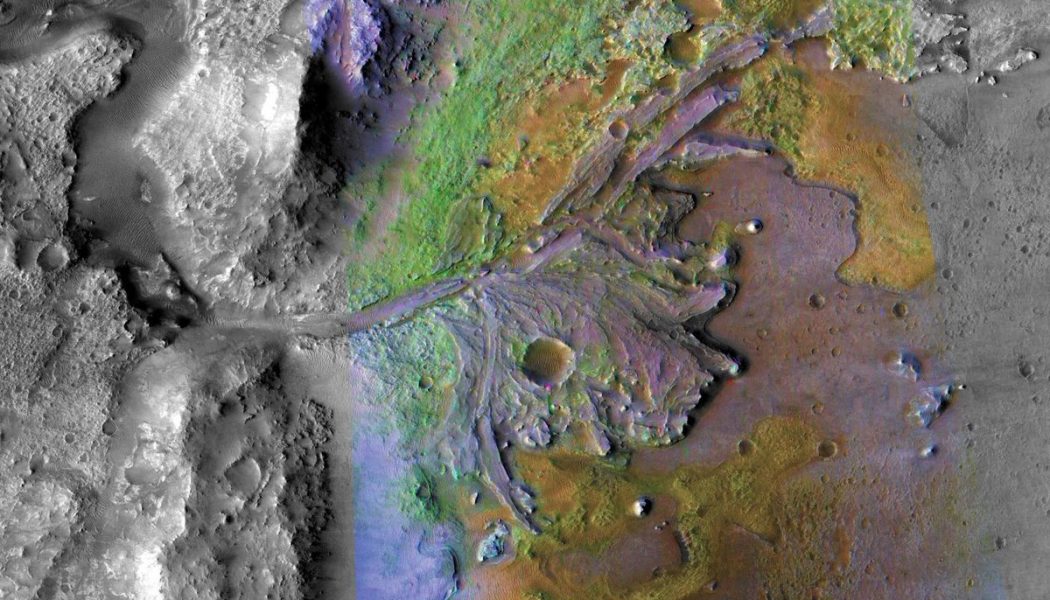

Fast-forward to today, and NASA picked perhaps the most tantalizing place for Perseverance to explore: a region on Mars called Jezero Crater. Scientists are fairly certain that the crater was once home to a flowing river that poured into a lake. That flowing water may have brought sediments and other minerals into the lake, providing the right chemical recipe needed for tiny lifeforms to thrive.

“We are going to see what looks to us from orbit as a very, very habitable environment,” Ken Williford, the deputy project scientist for Perseverance at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, tells The Verge. “If there were microbes in that lake, they had every opportunity to colonize, especially, say, on the edge of the lake where you often find pond scum on Earth or this sort of just green goo at the edge of a pond or a lake. That’s like our holy grail.”

The Martian dig

Once Perseverance makes it to Jezero, the hunt will be on for so-called “biosignatures.” A biosignature could be a rock, mineral, or structure that is formed by living things. It could be chemicals that are produced by biological processes or organic matter — molecules made of carbon and hydrogen that comprise all of Earth life. Finding one biosignature would be incredible, while finding multiple types in one location would be a jackpot.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20534168/24759_pia23491_web.jpg)

Perseverance is decked out with seven instruments, most of which will look for biosignatures as the rover surveys the Martian terrain. They include cameras, radar, a laser, and more. Perseverance has a few side projects, too. One instrument called MOXIE will attempt to turn carbon dioxide in the Martian atmosphere into oxygen — a technique that may be useful for future human explorers of Mars. The glitziest addition is a tiny helicopter, which will attempt to fly through the thin Martian atmosphere.

The real pièce de résistance of Perseverance is its sampling system. “The sample return aspect is really sort of the biggest motivating objective of Mars 2020,” Williford says. “It’s our reason for being.” A robotic arm will extend outward from the front of the rover and drill into the surface with one of nine drill bits. The drilled material will be shuffled into one of the 43 titanium sample tubes that Perseverance brought to Mars. Once filled, a tube is brought into the belly of the rover, where another robotic arm takes pictures of the sample, hermetically seals it, and then stores it for later.

Entire teams of scientists and engineers will determine where and when Perseverance drills. They’re trying to plan as much as they can now, but it all depends on exactly where Perseverance lands within Jezero Crater. Once it’s on the ground, the rover can analyze its surroundings and highlight key areas of interest. The teams are on the hunt for certain types of rocks like carbonates, which have been seen from orbit surrounding the rim of Jezero Crater. They’re also hoping to spot bumpy mounds of layered dirt, known as stromatolites. Stromatolites form in shallow water environments on Earth when mats of cyanobacteria trap tiny bits of sediment, creating layered rock formations. Similar structures on Mars would provide enticing spots to drill.

[embedded content]

Ultimately, a decision to drill will take days to weeks of discussion, with scientists weighing thousands of different factors. “Each sample will be incredibly valuable, and really one of its kind,” says Bosak, who is part of the team of scientists making the decision on where to drill. “But while valuable, we can be paralyzed also by: ‘Oh is this as valuable as something around the corner could be?’ We’re still working out what exactly is good enough, because maybe around the corner is worse.”

Weathering Mars

The goal is to get at least 20 samples of diverse material that can be returned to Earth one day, though the option is there to fill all 43 tubes. “If you ask all the engineers, it’s 43,” Eric Aguilar, a system testbed manager and assistant product delivery manager for the sample caching system on Perseverance at NASA JPL, tells The Verge. “We want every single one taken and working and have a sample, and then make it really hard for the scientists to decide which ones to come back.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20534171/pia23919_1041.jpg)

At some point, scientists will make the decision to drop the sample tubes somewhere on the Martian surface. It’s possible they’ll decide to dump the tubes in ones and twos, or most likely in one big grouping on a flat surface somewhere. Since they’re made of titanium, the sample containers should be able to withstand the cold Martian environment — as well as any potential dust storms — without losing the precious contents inside them. They’ve also been painted white in case things heat up on Mars, too. “We don’t want these things to get overheated on the surface of Mars, even though it’s still pretty cold up there,” Aguilar says. “But in direct sunlight it can get fairly hot, too.” All in all, NASA claims the tubes will be able to last for up to 20 years without degrading.

That’ll be key since it’s going to be a long wait until the follow-up mission. NASA and the European Space Agency are working together to help speed things up. The mission will likely send another rover to Mars to collect the samples and then take them to a rocket, which might meet up with another spacecraft in orbit. That spacecraft will then start the journey back to Earth with the samples. It’s going to be incredibly complicated, and scientists are looking at a wait that could last up to a decade.

[embedded content]

But if it all pans out, the results could be tremendous. Once on Earth, scientists would be able to take the samples and slice them down into thin sheets of rock. “We ultimately polish it down until it’s thinner than a sheet of paper, so you can shine light through it,” says Williford. “And this then allows you to see very, very tiny things the size of individual microbial cells. We can’t really do that quite yet with the instruments that we can fly on a Mars mission. But if we get the samples back, we can do that.”

Getting to the launchpad

There is still quite a lot of work left to do, but just getting to this point is an achievement for the Perseverance team. The idea of a Mars sample return mission has been on the minds of scientists for decades. “People would laugh and say we’re always 10 years away from Mars sample return,” says Williford. “That was the joke, because this is something people have wanted to do at least since the Apollo era.”

Because of the nature of Perseverance’s mission, many extra precautions had to be taken. Above all, the rover has to be incredibly clean to avoid any contamination of Mars. Engineers baked the rover at more than 300 degrees Fahrenheit (150 degrees Celsius), to completely sterilize it. “When we collect that sample, we have to make sure when we open it up and we interrogate it for possible ancient microbial life, that we don’t say, ‘Hey, big newsflash, we found life on Mars!’ And come to find out, it’s actually something that hitched a ride from Earth,” Moogega Stricker, the lead for planetary protection on Perseverance at NASA JPL, tells The Verge.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20534277/20200726144657_460452.jpeg)

During the final stretch of launch preparations, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, forcing engineers to completely rework their plans. The team worked in shifts to enforce social distancing and added extra cleaning and disinfection precautions to make sure they didn’t spread the virus to their colleagues. There were struggles with the rover’s ride to Mars, too. The Atlas V rocket slated to launch the mission experienced some issues during a test in June, forcing the team to push back the launch by a few weeks. There’s only a small window of time this summer for Perseverance to launch when Mars and Earth come closest together on their orbits. If the rover can’t launch before late August, NASA may have to wait another two years to try again.

Perseverance is now days away from its scheduled launch on July 30th at 7:50AM ET. The vehicle will take off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, putting Perseverance en route to Mars with a scheduled arrival date sometime in February 2021. It’s the same month that two other spacecraft will arrive at Mars: an orbiter built by the UAE called Hope and China’s Tianwen-1 mission, which also includes a rover.

Next February, Perseverance will descend to Mars, a daring feat that only eight missions have successfully pulled off. It’ll be the most harrowing part of the journey, often described as seven minutes of terror. But if Perseverance can get down to the ground in one piece, the real work can begin. Whether or not Perseverance finds life, it could give us important insights into the nature of our Solar System — and the Universe.

“The central question of ‘Is there life on other planets?’ — it really comes down to: is the origination of life some kind of magic spark that happens only incredibly rarely, or alternatively, is it the kind of thing that is inevitable?” says Farley. “What we can do is we can go to such place in our own solar system on Mars and ask the question, ‘Is life ubiquitous?’”