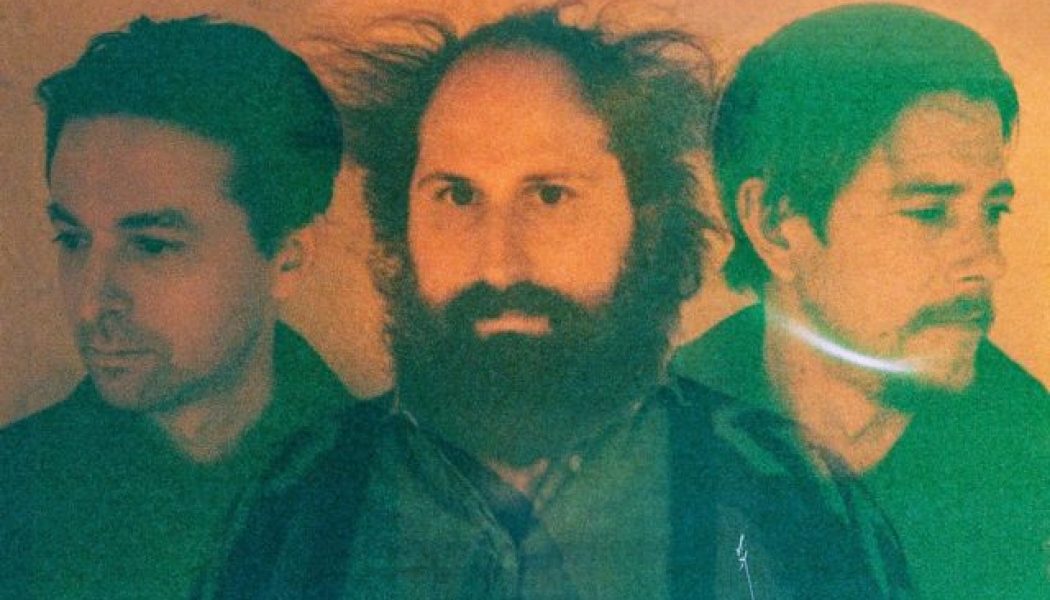

Paul Banks swears that he never intended to form another band. The singer-guitarist had a busy enough work schedule with his main outfit, Interpol, not to mention other diversions like Banks and Steelz — his side project with rapper-turned-film-director RZA — and solo albums as Julian Plenti and under his own name, like Banks in 2012. But he couldn’t help himself with his new trio Muzz — the chance to work with his childhood guitar-whiz chum Josh Kaufman (of Bonny Light Horseman renown) and their mutual percussionist pal Matt Barrick just proved too tempting.

And his instinct was on the money.

The eponymous Muzz debut is a moody, melodic masterpiece, falling somewhere between the delicate melancholy of the Blue Nile and the sinister atmospherics of vintage The The, which is held together by Banks’ ennui-steeped, Velvet Underground-chilled vocals.

There’s a windswept melancholy coursing through the record, as well, uniting disparate tracks like the delicate “Bad Feeling,” the machine-gun-rhythmic “Knuckle Duster,” a mournful “Broken Tambourine,” a light, uptempo “Chubby Checker,” the loping “Everything Like It Used to Be,” and the decidedly-Interpol-sinister processionals “Red Western Sky,” “How Many Days,” and “All is Dead to Me.” Nothing feels forced; the musicians seem to have instantly clicked and found their own synthetic voice.

Or, as Banks phrases it, “A lot of things have gotten simpler as I’ve gotten older, and one of those things is that I can I can identify creative chemistry pretty quickly now. And if it’s fun for me? I do it. And also, if I feel like my collaborators are immensely talented, and that I may well be the least talented person in the room, that also feels very safe for me. I just enjoy making music with super-talented people.”

From his sheltering-in-place hideout in Scotland, Banks checked in to discuss Muzz’s curious genesis, as did Barrick from his lockdown locale in Philadelphia.

SPIN: Paul, you were always a huge chess aficionado. Are you still playing online now?

Paul Banks: Yeah. Every day. I’ve got multiple games going with buddies, and then I’ll just play random people on chess.com, the app. It’s great. I play speed chess — I play three-minute games. And that’s the only way I’m good at chess, actually, is with the time clock.

Has your mastery of chess ever given you any new songwriting skills?

PB: I don’t know. If anything, it would give you the exercise of thinking harder, and that can always benefit you. But I also think that for me and music, I’ve learned more from things that I’ve deemed to be kind of instinctual. Like, I had an epiphany with the game of pool at one point, which is that you never have to line up a shot with your cue or the rail, because once you have a proper stroke with a pool cue, my belief is that our physical coordination is way, way expert, so the only time you’d be misjudging the shot angle is when you’re thinking too hard about it. But if you just tapped into the instinctual side of things that instantly processes geometry, then a pool-shot angle is very easy to see if you just awaken to that first instinct and follow through with it, without getting caught up in your own head. That applies to music maybe more than what chess has given me. It’s about obeying instinct and functioning whenever possible in that zone.

And lyrically, you were always an observational writer, sometimes sketching ideas in bars on cocktail napkins. But what do you do when there’s nowhere to go and observe in our post-pandemic era?

PB: Well, right now I’m writing mostly music stuff, so no lyrics. But actually, I wrote a song with lyrics recently, so I would say that the events happening certainly are factoring in to lyric writing, and I do think that — having such an observational bent — it does frustrate a part of my subconscious when you’re kind of in the same space, seeing the same things all the time. And I think that’s probably pretty universal. But I think that there are loads of weird psychological nuances that are going to happen across the world that people probably have only manifested on submarines and quarantines in the past. And then what degree of separation anxiety will develop? Will it be weird to not be attached by the hip to the person you’ve been quarantining with? I wonder about everything — How many relationships are doomed? How many are re-solidified? And how many people will just quit their jobs?

But the seeds for Muzz were planted a long time ago, right? When you and Josh first met in school overseas?

PB: Yeah. At the American School in Madrid when we were 15. He arrived in our sophomore year of high school, and we had English classes together. And then I learned that he played guitar, and I was a guitar player at that point. And he was one of the only people I knew who played, and he was preternaturally good at it. So we were drawn to each other’s sense of humor and tastes in music. And also, when you’re a 15-year-old aspiring musician, anybody else who’s kind of into what you’re into? It’s like, “What’s up with YOU?”

Then you both moved back to New York, but didn’t form a band right away?

PB: In the very early days — before Interpol took off — Josh played with me live when I was doing my solo stuff as Julian Plenti. So I have a folk-acoustic-guitar-open-mic kind of background. That’s where I started, with a lot of influence from artists like Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Neil Young and Buffalo Springfield. And that’s where Josh and I really bonded all those years ago. But then I was in Interpol, and Interpol just took off, while Josh was in upstate New York, learning composition. And I’ve thought about this — Why so long to collaborate in a formal capacity in Muzz? And I really think it’s kind of cosmic. We do have this history, where he was a guitar mentor to me since we were very young, and I just went in one direction, and he went in another direction. And in between Interpol records, if I was doing solo material, it was a point of pride for me to just do it alone. I was not open to — or looking for — collaboration. But Matt was helping me with what was going to be my next solo record, and we were working on a couple of songs. And when he said, “Why don’t we have Josh come in on these?,” it was at a moment in my life where I was suddenly ready for that type of collaboration.

So you were the linchpin, Matt?

Matt Barrick: Yeah. Paul and I had been playing together in Banks and Steelz, and at the end of that he would send me demos and we were starting to work on some things. And separately, I had been working with Josh for decades, and in 2015, Josh and I had gotten together here in Philly in my old practice space and we did a couple of demos. But nothing really came of it. And suddenly I just thought of that and suggested that we bring Josh in on what we were doing. He’s just an Uber-talented guy, but once all three of us got working, we had a chemistry that was really good. And we ended up bringing in all those old demos, and one of them, “Knuckle Duster,” made it onto the record. And “How Many Days” was one of our first songs, actually. I remember we were on the Banks and Steelz tour, and we were at soundcheck one day, and I started playing that beat. Then Paul said, “Hey!” And started playing these chords on top of it. So we already had that song, sitting around as a demo. A demo that became part of the album.

PB: And Josh sent me some songs that he had built up by himself in the studio, with no vocal treatment, so we had — in the very beginning — songs that I was bringing in, songs that Matt and Josh had done together, and songs that Josh was bringing in. So we had this pool. And I loved all the songs and I thought I had a role as a vocalist in all of them. I was like, “Cool. We’ve got a LOT to work with here.”

There’s an eerie prescience to the forlorn feeling of these songs, too. A record for — and of — its coronavirus time.

PB: Yeah. I’ve been hearing that. And a song like “Broken Tambourine,” which was written before lockdown — I was doing the video treatment for it, and I felt that it was really appropriate for the moment. But it wasn’t until I started thinking about lyrics to other songs that I realized, “Oh, shit — everything is NOT like it used to be, but this album certainly speaks to the moment. But I think that this was a record that was just filled with the right kind of inspiration. But basically, as this goes into the rear-view mirror, the world will return to normal more than we think, and maybe more than it should, in some ways. And I’ve heard that some nations are trying to restart their economies with a more sound and environmentally-conscious model. And that sounds really beautiful to me, like an incredible silver lining.

And Muzz can continue, right alongside Interpol.

MB: Yeah. I think we will definitely continue to make music together. And as a matter of fact, we’ve already started recording some new stuff in lockdown…

![John Digweed on the Intricacies of a VR Festival Performance and the Impact of COVID-19 on Dance Music [Interview]](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/john-digweed-on-the-intricacies-of-a-vr-festival-performance-and-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-dance-music-interview-327x219.jpg)