Like many in her age range, 97-year-old Sylvia McGregor of Sydney deals with her share of maladies — in her case, arthritis, osteoporosis, hearing loss, macular degeneration, lung disease, hypothyroidism, chronic kidney disease, heart disease and two total knee replacements. But unlike most nonagenarians, she does intensive strength training twice a week.

She credits the exercises, which she has been doing for 12 years, with allowing her to live independently. “I still live by myself, and I take care of myself,” she says. “It was only when I was in hospital [in 2021] that they said I had to have a walker to go back home alone. So I said, ‘That’s okay by me.’”

McGregor is in one of the fastest-growing age groups — individuals age 80 and older. By 2050, this “oldest old” group is expected to triple in number to 447 million worldwide.

Their longevity reflects improved management of chronic health conditions that lets older adults live longer even if they have serious health problems. But physical function deteriorates as people age, and many older adults become unable to take care of themselves — eroding the quality of those extra years and decades.

Exercise is the best prescription for maintaining independence, researchers say. But what is the right dose — in terms of frequency, intensity and duration? What type of exercise is best? At what age do you need to start — and how late is too late?

There are too few studies about exercise among the oldest old to offer definitive guidelines for that age group, says Erin Howden, a researcher and exercise physiologist at the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute and co-author of an overview of exercise in octogenarians in the 2022 Annual Review of Medicine. But evidence for the “younger older” — people ages 60 to 75 — is sufficient to provide good, basic advice to anyone who wants to still be working in their garden at 97.

Independent living requires the ability to perform the activities of daily life — bathing or showering, dressing, getting in and out of bed or a chair, walking, using the toilet and eating.

Doing these things takes four physical attributes: cardiorespiratory fitness (how well the cardiovascular system and breathing apparatus supply oxygen during physical exertion); muscle strength and power; flexibility; and dynamic balance, meaning the ability to remain stable while moving.

Biological aging takes a toll on each of these.

Cardiovascular fitness — the ability of heart and blood vessels to distribute and use oxygen during exertion — declines throughout adulthood as our circulatory capacity decreases. That decline speeds considerably late in life. Over 70, cardiovascular fitness falls by more than 21 percent per decade — and that’s for healthy people. Prolonged inactivity and common chronic conditions such as heart failure, diabetes and obesity make the situation worse. It is common for octogenarians to have cardiovascular function so low that it plays a part in preventing them from performing basic activities such as vacuuming and cooking.

Dynamic balance, essential for walking, stair-climbing and avoiding falls, declines also, thanks to deterioration of the musculoskeletal system and of neurologic function. And muscle mass decreases by about 3 to 8 percent per decade after 30, with decline accelerating after 60. That often reduces both muscular strength — the ability of muscles to exert force, allowing us to lift objects — and muscular power, the ability to do work quickly, which we need to climb stairs. The more immobile you are, the faster this wasting can proceed.

This muscle loss, known as sarcopenia, is why walking, one of the most popular forms of exercise, may not be enough to keep us operating independently.

“People think, ‘Oh, I walk,’ but walking will not help you build muscle,” says public health scientist Rebecca A. Seguin-Fowler, associate director of Healthy Living at the Texas A&M AgriLife Institute for Advancing Health Through Agriculture.

The federal government’s exercise guidelines for adults recommend at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (or 75 minutes of vigorous activity), along with muscle-strengthening exercises such as lifting weights or working with resistance bands — at least eight to 12 repetitions for each exercise — at least two days per week. To that, people 65 and older should add balance and flexibility training — think tai chi, Pilates or yoga — about three days a week.

There are lots of ways to tick the aerobic exercise box. An analysis of 41 clinical trials involving older people with an average age of 67 found that many regimens work, including walking, running, dancing and other activities, at different intensity levels and durations. In general, the more frequently a person exercised, the greater the benefit.

Aerobic training earlier in life is better to prevent — and at younger ages, even reverse — the normal age-related stiffening of the arteries that is a risk factor for hypertension and stroke. For example, a small study of 10 healthy but sedentary people 65 and older who over the course of a year worked up to 200 weekly minutes of vigorous aerobic exercise improved their cardiovascular fitness, but the training had no effect on their arterial stiffness. In contrast, a small study of adults ages 49 to 55 found that cardiovascular fitness improved and cardiac stiffness lessened through a combination of high-, moderate- and low-intensity aerobic exercise for 150 to 180 minutes per week for two years.

Howden, who led the second study, sees a clear takeaway: “Middle age and late middle age is when we need to get serious about incorporating a structured exercise program into our daily lives.”

And muscles? Two decades of research have shown that resistance training can prevent and even reverse the loss of muscle mass, power and strength that people typically experience as they age. Here is what works, according to an analysis of 25 studies involving people 60 and older, with an average age of 70: Exercisers should have two sessions of machine-weight training per week, with a training intensity of 70 to 79 percent of their “one-rep max” — the maximum load that they could fully lift if they were only doing it once. Each session includes two to three sets of each exercise and seven to nine repetitions per set.

As for fitness for the oldest old, the first study of this group was a clinical trial with 100 frail, elderly nursing home residents in Boston. The average age was just over 87, and more than a third of participants were 90 or older. The vast majority — 83 percent — used a cane, walker or wheelchair; half had arthritis; many had pulmonary disease, bone fractures, hypertension, cognitive impairment or depression.

Individuals assigned to the exercise group completed a regimen of high-intensity resistance training of hip and knee muscles three days per week for 10 weeks. For each of the muscle groups, resistance machines were set at 80 percent of the one-rep max. The training was progressive, meaning that the load was increased at each training session if the individual could tolerate it. Sessions lasted 45 minutes, and at each session, the exerciser completed three sets of eight lifts for each muscle group.

By the end of the trial, exercisers had significantly increased muscle strength and mobility in their hips and knees compared to a group of non-exercisers. Four participants no longer used walkers after the training, getting by with a cane instead.

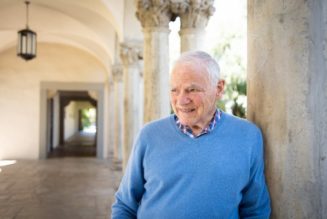

The lead investigator for that study was Maria A. Fiatarone Singh, now a geriatrician at the University of Sydney. For older people, she says, strength training, which helps with balance, is the top-priority exercise because it makes other forms of activity possible.

“Most people, including health-care professionals, still have this idea that the most important thing is to help people to walk around, but that is only important if they actually can walk around,” she says. “You have to have strength and balance first.”

Fiatarone Singh started the strength-training program in which McGregor and her elderly peers press weights twice a week, and nobody is getting off easy. “We actually increase the weight every time we see somebody when they’re first starting,” Singh says. “At some point, their gains are less steep, but they still gain muscle mass if you continue to increase the weight.”

When she looks at a graph of McGregor’s muscle mass over time — “Hers is rock solid” — Fiatarone Singh sees inspiration.

“When somebody who is in their 90s sees themselves getting stronger,” she says, “they will tell you how good it feels.”

This article was produced by Knowable magazine, where a longer version of it appeared.