_Moses%20Sumney.jpg)

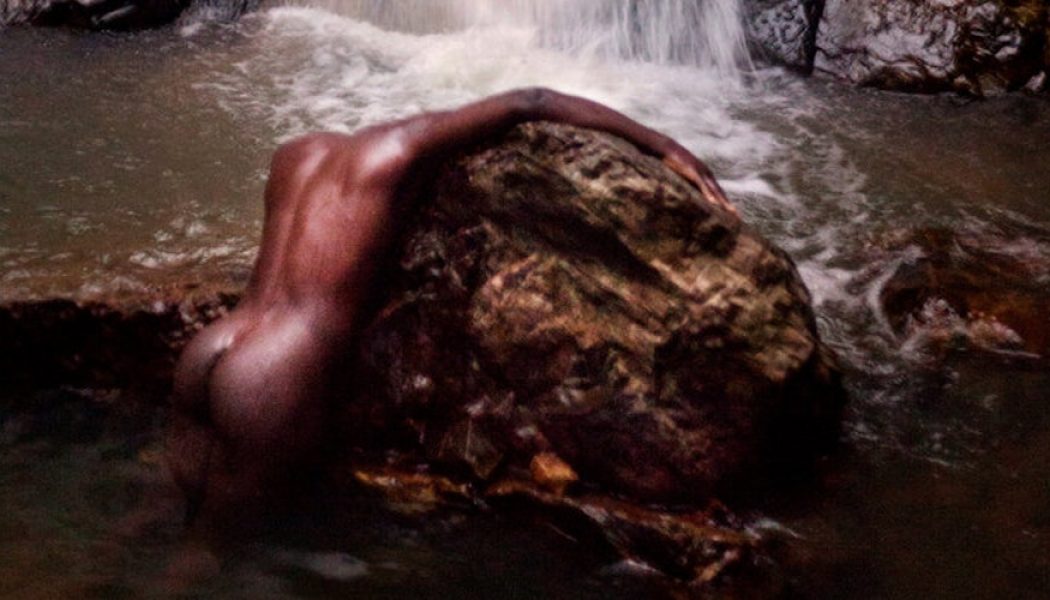

Last December, Moses Sumney debuted a video for a love song called “Polly” from his newly announced double album græ. It was about as unadorned a video treatment as possible: Sitting in front of his computer’s camera in a black t-shirt, framed by a white wall and some guitars, Sumney stared into our eyes while the song played. He did not lip sync as usual. Instead, he took a few deep breaths and began to weep, tears running down his cheeks. Every so often he gulped for air, but otherwise he remained still, and he never broke eye contact. Halfway through the song, he brushed his tears with his palm, a radiant smile escaping, his eyes warming. As the song played, its chorus stripping back longing to its pulsing root—”see see see see me”—he seemed to pass through something elemental and emerge on the other side, transfigured.

This facility for naked emotional connection is a kind of superpower, for good or ill, and Sumney has wielded his with grace. It’s the most significant of his many, many gifts, including his astonishing singing voice, which can plead like Prince or ascend to ANOHNI or Thom Yorke heights. He’s been overwhelming new converts ever since he opened for the R&B trio KING in 2013. He spent the next several years deciding what to do with the vast possibilities his talent afforded him. Sidestepping a cresting wave of industry attention better known for ruining careers than starting them, he waited until 2017 to release his starlit debut Aromanticism on the indie label Jagjaguwar.

That album, though decked in swirling string and horn arrangements, was quiet, intimate, and burned with the intensity of a few glowing embers. The most significant element in the mix, after his voice, was silence. He seemed at rest, drawing in one great breath and waiting for the moment to exhale. There was more to come, the album hinted, more to say, but not yet.

On græ, he lets out everything inside of him. The album is bigger, in every sense—longer, for starters, a 20-song double album that Sumney saw fit to release in two parts (the first half of the album appeared in February, the second arriving only this week.) Where Aromanticism was intimate and sleek, græ is rangy, sprawling, a riot of moods from lustful to angry to broken-hearted. He has summoned a battalion of collaborators, including production from Daniel Lopatin, basslines from Thundercat, saxophone from Shabaka Hutchings, horn parts from the English art-rock group Adult Jazz, writing credits from James Blake and author Michael Chabon. The camera lens zooms out from dewdrop to mountain range. Everything Sumney’s ever done or tried to do is here.

“Virile,” the single that preceded “Polly,” is in many ways more representative of the album’s omnivorous ambition. In the video, Sumney convulses across the fog-swirled floor of a meat locker, his body as flawless as a marble statue while carcasses swing behind him on hooks. The lyrics are a withering send-up of the pointlessness of toxic masculinity in a world where the body inevitably turns “to dust and matter.” “Cheers to the patriarchs,” he sings bitterly over bludgeoning stabs of guitar from Noah Kardos-Fein of the NYC noise-rock duo Yvette and string arrangements from Rob Moose. Like Perfume Genius’ Mike Hadreas, Sumney mingles the cerebral and the carnal, eroticism and disgust, until the sensations are indistinguishable.

He also shares Hadreas’ yearning to escape his own shell. On “Gagarin,” which interpolates a piece by the late Swedish pianist Esborn Svensson, Sumney sings in a pitched-down voice of wanting to “surrender my life to something bigger than me.” (The title is a likely reference to the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, the first man to travel to outer space.) Sumney’s voice pours like tar onto the sound of a jazz piano and eventually the whole track turns ectoplasmic. The final minute sounds like the birth of a universe, with synths streaking like stardust before melting down amid the formless cries of Sumney’s digitally altered voice. The HD sheen of the mix—you can practically see the air tremble around the cymbal splashes—is a bold contrast with the formless abstraction of the music, like a private-press 1970s new age record remastered by Dr. Dre.

Though he might not harbor their commercial aspirations, Sumney shares some of the precision and remove of auteur figures like Dre or Trent Reznor. He controls every aspect of his art, from his flyers to the art direction of his videos, and so his music arrives seemingly whole and untouched from a different universe. It also means his work can feel a little cool to the touch, even when his lyrics are strictly autobiographical (“I had two dogs in 2004” is a good representative lyric). His voice is an instrument of pure beauty, a falsetto so dazzling he could trace a cathedral with one syllable. It also tends to turn his words into color, mere vehicles for him to cast light and shadow against the wall. The music is gorgeous, an empty word that often points to the missing thing in Sumney’s work: The stray hair, the smudged line, the wrinkle on the outfit that proved somebody once wore it.

Running through the album are the sampled vocals of the Nigerian-Ghanaian author Taiye Selasi, whose ruminations on multiplicity and identity glue together the album’s edges. “I really do insist that others recognize my inherent multiplicity, Selasi says on “also also also and and and.” “What I no longer do is take pains to explain it or defend.” The dreamy piece culminates in a manifesto of sorts: “I am aware of my multiplicity, and anyone wishing to meaningfully engage with me or my work must be, too.”

These pieces probe the album’s underlying consideration: How to account for your whole self, not just the pieces that you feel comfortable offering to others. For Sumney, the most precious commodity is space—space to test out your voice when no one else hears it, space to struggle your way towards self-definition. Despite his emotional transparency, Sumney seems a little ambivalent about unbridled self-expression: “Bystander” is a wry ode to the wisdom of keeping your mouth shut. “Honesty is the most moral way/But morality is grey,” he observes, in one of the album’s most tenderly sung lines.

The most powerful moments on græ examine the distance between this wariness and the loneliness it produces. “I am not at peace with dying alone/But I am not at war either,” he sings on “Neither/Nor,” a negation that might be Sumney’s most resounding statement of self. His music is unique in the chilly way it yearns for warmth; he can often be coy, flirtatious, beseeching. “Sometimes I want to kiss my friends/You don’t want that…do ya?/You just want someone to listen to ya/Who ain’t tryna screw ya,” he croons on “In Bloom.” The stacked harmony vocals bear down on the line “Sometimes I want to kiss my friends,” and it proves as indelible, and maybe more meaningful, than his ideas about patriarchy or creative sovereignty.

For all of græ’s high points, for all the elasticity of its ambition, Sumney’s most exalted work still happens at the emotional distance of the “Polly” video. “Polly,” like all of Sumney’s most devastating and resonant music, exists only by the grace of his calloused hands fingerpicking a simple pattern and his voice, which does more to generate cosmos than all the prodigious talents on græ combined. The album highlights—lullabies like “Lucky Me” or “Me In 20 Years”— come from a place where Sumney often finds himself: his glittering voice, resplendent and alone, aching in solitude. This is the range of the coffeehouse whisper, his hand atop yours on the table. This is still where we feel him most.

Buy: Rough Trade

(Pitchfork earns a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)