“Rap is more than just a blessing. It’s mandatory that our generation have this music. Pain is a lot easier to deal with when it’s ours—not just yours.” – DMX, The Source January 1999

DMX fell on Good Friday. In the late hours of April 2, 2021, he was hospitalized following a reported overdose. He wasn’t a deity sacrificed for humanity’s sins, but he was the barking, growling, and God-fearing prophet of Yonkers. Every album was a prayer for deliverance from his pain and redemption for his sins. He shared it all as a sacrifice for the similarly afflicted. The temporal coincidence of an overdose, like much of X’s unfathomable and often tragic life, almost seems divinely ordained.

In the following days, we learned DMX suffered cardiac arrest. The 50-year-old rapper, actor, and father who once dominated both the charts and a stacked Def Jam roster was virtually brain dead, but the rap community hoped his endlessly tormented soul was still fighting off eternity. We prayed for a full recovery — the borderline resurrection of a most religious man on a most religious weekend. Easter came and went. When Dark Man X did not rise on the third day, the New York Post ran a reprehensible story cataloging how many homes he’d lost in his lifetime.

Then, on April 8, following a misleading Instagram story and a plague of premature social media eulogies, we learned X’s organs were failing. The confirmation of what we’d known but didn’t want to accept came the next morning. The Dog had slipped, fallen forever.

“We are deeply saddened to announce today that our loved one, DMX, birth name of Earl Simmons, passed away at 50-years-old at White Plains Hospital with his family by his side after being placed on life support for the past few days,” his team said in a statement on April 9. “Earl was a warrior who fought till the very end. He loved his family with all of his heart and we cherish the times we spent with him. Earl’s music inspired countless fans across the world and his iconic legacy will live on forever.”

Search social media mentions for rappers who’ve released a handful of albums in the last decade. You’ll see “icon” and “legacy” used with such abandon that future generations may have difficulty discerning history from nostalgia-driven hagiography. DMX actually was an icon. You can illustrate his legacy in so many ways.

That legacy was inextricable from the biography that began in Yonkers, the physical and psychological wounds he sustained, overcame, and to which he ultimately succumbed. To truly understand the gravity of it all, reading X’s 2002 autobiography, E. A. R. L, is highly recommended. What follows is a truncated and incomplete summary of the first two and half decades of his life.

As a child — in addition to suffering from chronic asthma that landed him in the hospital — X was physically and emotionally abused by his mother. He stole to eat before he reached his teens and fought with students and teachers until his mother abandoned him at a reform school. When hip hop became his creative outlet, he began beatboxing and adopted the name DMX after the Oberheim DMX drum machine. But that idyllic period of discovery quickly grew dark. Without a word, an older friend and rap mentor passed him the cocaine-laced blunt that sparked X’s lifelong addiction. Even among stints in juvenile detention and jail, robbing to support his drug habit, and becoming a father, X made a name for himself as a fierce battle rapper. Despite landing in The Source’s Unsigned Hype column, it took seven years before Ruff Ryders management landed him a record deal. The rest is rap lore. Irv Gotti brought Lyor Cohen to Yonkers, and X ripped shit with his jaw wired shut — the result of a brutal assault by several men for something he allegedly didn’t do. The wires were practically breaking, and Cohen was elated.

Between 1998 and 2003, he had five consecutive No. 1 albums. The first three were multi-platinum. Two of those three were released in the same year (1998), a feat that no artist may ever match. His debut, It’s Dark and Hell is Hot, was still selling 50,000 physical copies a week eight months after it dropped. Rap is rife with sports analogies, but no player or team comparison seems apt. DMX went undefeated in the regular season and the playoffs for five straight years. He might’ve been signed to Def Jam, but he was a dynasty unto himself.

The singles didn’t hit the same commercial highs as the albums, but that’s largely because they were too raw for radio. “Get at Me Dog,” “Ruff Ryders Anthem,” “What’s My Name?” and “Party Up (Up in Here)” all distilled anger, aggression, and adrenaline while becoming ride or die anthems. Each one rang out from the most impoverished ghettos to gated communities. They were soundtracks to heated park basketball games and skull-fracturing brawls in grimy clubs that searched for weapons at the door, but they also hyped up high school locker rooms before games and terrified neighbors at parties in moneyed suburbs. Play the songs above in succession, and you might wake to find holes punched in your wall, a baseball bat lodged in your TV, and blood-stained Timbs on your feet. Or maybe you’ll just dust off your PS2 and put in Def Jam Vendetta.

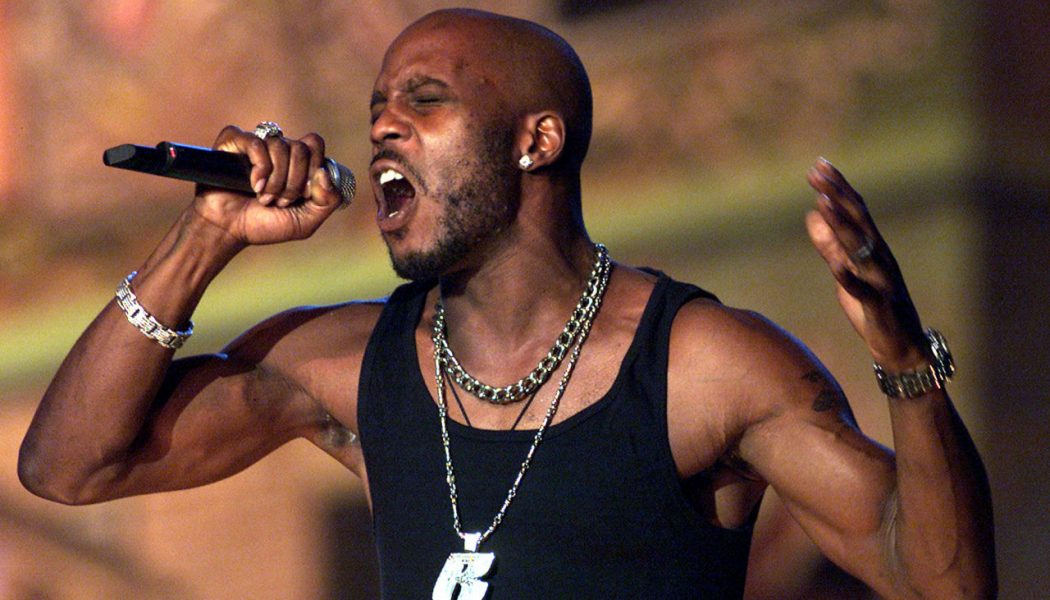

If authenticity is the fifth element of hip hop, DMX is the poster child. For better or worse, you could trust every rhyme, threat, and cry for help. You heard the truth in his lean, unsparing writing and gruff voice. He narrated every life-enduring trauma, prison sentence, and personal trial — both before and during his ascent — in a graveled, lacerated rasp. It inspired excitement, violence, fear, and most importantly, recognition from those enduring the struggles he temporarily transcended. He forever sounded pissed off and in pain, as if he just finished his last Newport and needed to hug or hit someone immediately. His voice could boom above ATV’s roaring through the hood just as easily as it could command a sea of fans at Woodstock ‘99 to cross their arms in reverence of a defining performance. The studio and stage were the pulpit. From both, he delivered sermons on the evil he’d endured and the evil he would perpetrate out of necessity or provocation. He didn’t tell you to sin, but he understood most of the reasons why you might. His legacy was connecting with the dispossessed, the mentally scarred, the victims of tragedies in governmentally targeted and neglected communities of color. You couldn’t bark in everyday life, but you could put on DMX and exorcise all of your rage and anguish. DMX knew. That was by design.

“I want Flesh of My Flesh to be like my connection to the community. I want to say what’s on their minds, soak up all their pain,” he told The Source for a January 1999 feature centered around Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood, his second album to debut at number one in 1998. “I’ve learned that when I take it all in, I can make one brotha’s pain be understood by the world.”

Reflecting the pain of his community meant rejecting — or at least not flaunting — the extravagances his success afforded. There was always more to a song “than jewelry and clothes,” more to his life “than money and hoes” (“More 2 a Song”). Even on “Ruff Ryders Anthem,” he battled his demons: “All I know is pain, all I feel is rain / How can I maintain with that shit on my brain?” He devoted entire songs to unpacking his battle with addiction: “Wasn’t long before I hit rock bottom / Like damn look how that rock got him” (“Slippin’”). And is there a better demonstration of his destructive commitment to radical transparency than “Look Thru My Eyes”? At the peak of the bottle-popping, Rollie-waving, patent-leather-suit-rocking era of the late ‘90s, DMX came in without a shirt, figuratively snatching chains and watches while ripping patent-leather to shreds. The flashy facades helped no one.

“A thug will do anything to get his, but he wants to help his people,” he told SPIN in 2000. “I don’t want to see any kid that reminds me of me or my family when I was younger — all hungry or needing shit. When fake thugs talk, the pretty bitch shit comes out: I get my nails done, I got jewels, look at my shoes. Fuck that.”

None of this was performative. DMX matched what he said on record and interviews with real action. Watch the video for “Where the Hood At?” from 2003’s Grand Champ. With four platinum albums behind him and millions in the bank, he went back to the School Street Projects in Yonkers. The video is less about X and more of a visual love letter to the people still living, loving, laughing, and struggling in that neighborhood. You see their joy, pride, and literal scars. X was the icon, but the people were always close behind him.

In less than a decade, DMX went from a couch-surfing addict to a multi-platinum superstar without compromising a single lyric, capitulating to trends or conceding to any label. He acted in movies that spoke to the culture (Belly) and those that topped the box office (Romeo Must Die, Cradle 2 the Grave). Unfortunately, in his post-Def Jam era, DMX still struggled with addiction and continued to get arrested. With nearly 30 arrests in his lifetime, he averaged more than one every other year.

Instead of conversations about therapy, the criminalization of addiction, and carceral recidivism, there were jokes. The dominant attitude for much of the late ’00s and early 2010s seemed to be “There goes crazy X again.” In Chris Rock’s movie Top Five (2014), DMX played himself. Of course, he was in prison. X was poking fun at himself, but so were Rock and the audience. He became the sad clown, singing Nat King Cole’s “Smile” and throwing in a “WHAT?!” ad-lib for effect. It’s funny only for a moment. The cameras were rolling, but this wasn’t fiction. DMX would return to prison in the following years.

Fortunately, X lived just long enough to be a free man once again. He saw the beginning of his final act, the shift from punchline to revered pillar, his return to becoming an icon. Anniversary pieces acknowledged the impact of his albums. BET ran a series on the impact of Ruff Ryders’ success, which was indisputably built on X’s back. During last year’s Verzuz event with Snoop Dogg, hundreds of thousands remembered the strength of his singles, the depth of his catalog, and the enormity of his being in real-time. X deserved to grace festival stages and sold out arenas once again, but the pandemic prevented that.

The official statement on DMX’s passing is correct in that “his iconic legacy will live on forever.” The music. The struggle. The sacrifice. But given the circumstances and announcement of his death, his legacy should continue in other ways. At an industry level, labels should be discussing mental health assistance and long-term healthcare for their artists — whether those artists put their pain on record or not. After seeing how quickly people rushed to commemorate DMX’s death after the inaccurate announcement the night prior, we should reevaluate our relationship with music icons. We should think about them as humans, treat them with greater empathy rather than rushing for clicks. It’s one thing to commemorate someone for what they meant to you, but it’s another thing entirely to make their impact about you. DMX made many songs about himself, but he was always barking, growling, and yelling while thinking of his audience.

“If anyone can look back on their life and know that they changed one person’s life for the better, then their life means something,” he told VH1 for Behind the Music. “And I’ve done that a hundred-fold. I’m alright. I say that with a smile in my eyes and a smile in my heart. I’m alright.”