This article originally appeared in the April 1986 issue of SPIN.

A battered motel room in Watts, the Glen-Dora Motor Lodge. When you come in, John Lee Hooker is standing at the stove in the cramped kitchenette. He’s cooking him up some red beans and rice, some biscuits and gravy, some neck-bones. Battered neckbones.

Or no, better—it’s a woman at the stove. A middle-aged black woman, thick at the hips, wearing puffy bedroom slippers. And John Lee Hooker’s settled in at the yellow linoleum dinette table with the rusty chrome legs. He has an old undershirt on, and as you come in, he looks up and says (nigh-perfect ZZ Top–imitation growl), “How how how how…”

No. John Lee Hooker is in bed. On the eighth floor of Santa Monica’s Bay View Plaza Holiday Inn. Half under the covers and half out, half dressed and half not, he’s watching the Dodgers and the Mets duke it out on the Game of the Week, his Robitussin cough syrup and his Tylenols and his prescription bottles all gathered right close at hand there on the bedstand. “Son,” he says kindly, warmly, mournfully, with a pitiful but resonant sob in his throat, “The blues ain’t nothin’ but a good man feelin’ bad.”

No. He says “Er-um. OK if I leave the game on?”

Now not only is this no Glen-Dora Motor Lodge, it’s also about the sharpest, slickest, sleekest Holiday Inn you’ve ever seen. It’s a scaled-up upscale postmodernish protomodel Holiday Inn, pink, with beach-gazing balconies enameled Kicky Green. This is a Holiday Inn with Ritz-Carlton envy, with leanings toward twice-a-day linen turn-down service, with hand-milled soap and high amenities, and maybe even the mystery chocolates—those bittersweet little bars of high-gloss chocolate that make their miraculous nightly appearance atop the fresh-plumped pillows. And John Lee Hooker’s holed up here at the Bay View Plaza—the Glen-Dora Motor Court can go straight to hell. Serves somebody else right to suffer.

In the interest of keeping this afternoon’s interview quick and concise and brief and businesslike, and in hopes of keeping an eye on the Dodgers—”I was a Dodgers fan ever since I was a kid”—Hooker goes right directly into the Standard All-Purpose Rap. Er-um. because by the time a guy gets around to becoming a sho-nuff Elderly Black Bluesman, he’s most likely been interviewed umpteen million times by urgent reverent blues scholars and indulgent reverent radio hosts and indigent reverent music journalists and tolerant reverent newspaper reporters, and by reverent reverent record-collecting nitwits too. And by the time a guy gets to be John Lee Hooker, Last of the Delta Blues Greats (the subhead over the newspaper story reads either “Mourns Death or the Blues” or “Says Blues Will Never Die“), the living link between country blues and uptown R&B, between the juke joint and the jukebox… well, long before John Lee Hooker got to be 68 years old, he polished him up a nice seamless Standard Rap, an all-purpose, all-comers set of stock answers to the Ten Most Deadly Obvious Questions: “Son, the blues ain’t nothin’ but a good man interviewed bad.

The Standard Rap is nearly as pure an artistic form as, say, the twelve-bar blues (although, as it happens, twelve-bar blues is a pattern that Hooker never much follows), a somewhat newer form, but steeped in deep traditions of its own. All the elder blues statesmen use it, and like the venerable blues itself, it was born of oppressive circumstance. Namely, the unending stream of white blues aficionados with interviews in mind, each one wearing all the predictable requisite beliefs strung together like rosary beads, each one thrilled to death to be hearing the straight skinny from the soulful source, each one dead set and determined to get the true scoop on How Did You First Get Started? and Who Were Your Major Influences? and What Do You Think of the Rock Bands Of Today? and especially, most especially, the one they always ask, all of ‘em, the archivists and the reporters and the radio hosts and the liner-note writers and the record-collecting numbskulls, the one they all want to know: What IS the Blues?

Elderly Bluesman interviewing Little Stevie Spielberg: “So tell me, man—What IS the Movies?”

John Lee Hooker’s own rote version of the standard recitation begins in the farmlands near Clarksdale, Mississippi, where Highway 49 and Highway 61 meet, the very heart of the upper Delta region, sometime around 1929. ‘Well, er-um. really I got started… er-um my stepfather, Will Moore, taught me when I was about 12 years old.” He starts slowly, but warms up and gets rolling good as soon as he hits a key word—drifting. “Er-um, I drifted up, get me a old guitar, I left there when I was fo-teen and I come into Memphis first, stayed there a couple months, went on to Cincinnati, stayed there about three years—I wa’nt lookin’ to get involved, you know. Driftin’. I played around streets, house parties, bars, gettin’ better and better at a young age. Then finally I drifts into Detroit when I was about close to 20. I played around there a long time, and when I got to be 21 I could play in the bars. And I got to be the talk of the town.”

And that comprises the first very concentric chorus of Hooker’s version of the very very Standard Rap—How I Got Started, How I Struggled, and How I Got Over, four bars of each. It’s a neat package, reinforced at the corners, suitable for framing, ready for more detailed embellishment should an especially diligent blueshound be on the case. And the details are worth knowing, too—Hooker’s life has been full. That step-father of his, Will Moore, played with Blind Lemon Jefferson and Charley Patton both, two of the truly primary patriarchs of the blues, two of those shadowy blue legends who make blues research such a tantalizing, prickly quest. And by digging a little deeper, by pushing Hooker toward even earlier choruses, the researcher discovers that little John Lee’s first singing took place in the local church choir—consider the choir that could incorporate John Lee Hooker’s pre-pubescent rumble-grumble!—and that his first electric guitar was given to him by yet another Legend of the Blues, the founding father of electric blues guitar, T-Bone Walker. The urbane T-Bone, a big-band man from Texas, a real showman with a soupçon of Kansas City swing salting his blues, dug John Lee Hooker, the roughest, rawest, rudest of guitar players, dug him enough to present him with a pawnshop prize—and this at a time when electric guitars were a good deal scarcer than ’48 Studebakers are today.

Ah, but the problem with the Standard Rap, advance-chewed and predigested and yet interesting all the same, Is that it interferes with the possibility of getting on down to the real questions, the revealing questions. The ones (What IS the Blues?) that ache to be asked. Like, for instance: How come the young guys in white blues bands never wear nylon pimp sox?

And they don’t either. It’s weird. And totally undocumented in the scholarly journals. Because white guys in blues bands will do anything—anything—to be just like their blues-hootin’, blues hollerin’ blues heroes. They’ll quit school and get regular jobs and even quit callin’ their parents long-distance for money lust so’s they’ll have really paid some dues. They’ll scrimp and scrape and suffer, they’ll smoke way too many Lucky Strikes—filterless ones, even!—and they’ll swig out of passed-around half-pint bottles without wiping off the top. They’ll commence to chewing on matchsticks. They’ll take to beating their wives and kicking their dogs and borrowing money from all their old friends and then ditching them—anything to achieve that elusive urban blues authenticity… but they just won’t—just can’t—put on the pimp sox, the nylon/ polyblend socks with 3 percent genuine Ban-Lon and the hi-contrast textured ribs stretching over the ankle knobs like a Bareback Pleasure Stretch condom on Soul Fiesta colors of maroon or lemon or midnite blue, the stylin’ and smilin’ sox that three generations of pimps and players and pushers and preachers alike have sworn by, one and all.

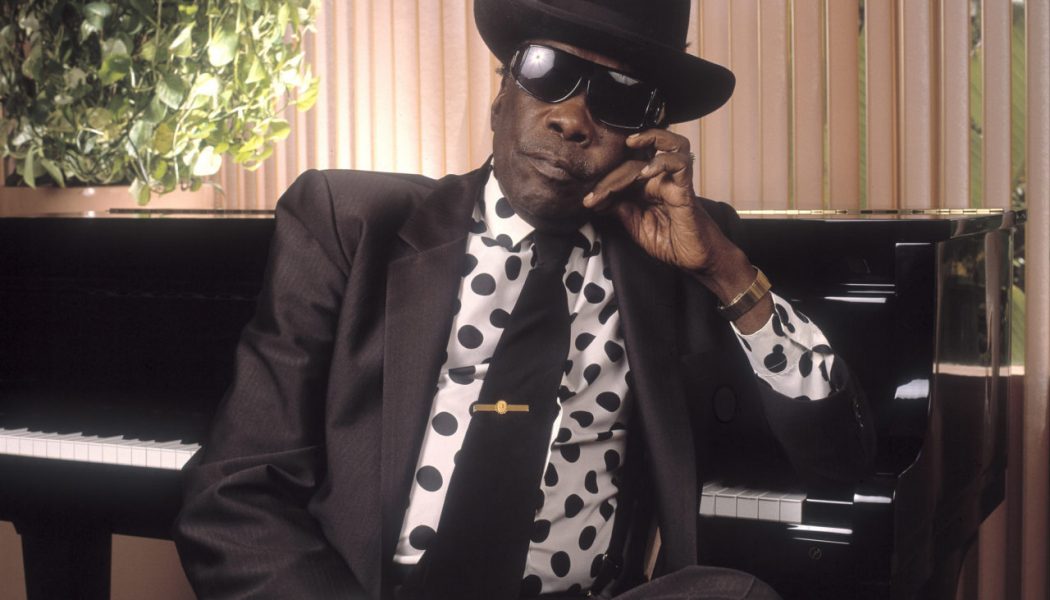

You’ll see them sometimes, the young white blues guys, up on the stage backing some touring semi-legendary blues notable or seminotable touring blues hopeful. (In Phoenix, Arizona for example, some of the local indefatigable enthusiasts, lacking a whole lot in the way of an authentic regional bluesman suitable for installation as their band’s hood ornament, went out and rounded them up an African fellow who was working at Motorola or someplace; big and black and middle-aged, he fit the specs almost perfectly, hollering out the appropriate Delta-thickened syllables, Dtahp dah-hown mawmahw, toin yo’ lamp da-hown luh-ow… until he came offstage, where he carried on his conversations in one of those charming African colonial accents. He came up to me once at an Otis Rush show and said, “Sounds a good deal like Albert King, wouldn’t you say?”) You can see ‘em, the young white blues guys, up onstage backing some middle-aged blues notable, and he’ll be dressed pretty much the way John Lee Hooker is here at the Holiday Inn, if not quite so expensively. Because Hooker is sharp. The bedcovers are pushed back so you can see he’s wearing a pair of pimp sox, red ones that go nicely with his red polyester slacks and the red suspenders that set off the fine silky black undershirt beneath his half-buttoned red dress shirt with the wide, wide wingspan collar scheduled for takeoff across the lapels of the red jacket he’s draped over the chair by the dresser.

A pretty slick ensemble onstage, topped off with a white felt fedora—the prosperous look the older black bluesmen unanimously prefer. And back behind the older gentleman in the polyester-blend suit will be three or four or five white boys in their 20s and 30s, and as far as technique goes, they can probably play flashy 12-bar rings around the old black guy… but they just can’t do it— they can’t slip on a stretchy pair of those pimp sox or wear one of those polyester suits. The older of the white boys will wear vintage thrift-shop zoot suits, adding a hand-painted palm-tree tie to demonstrate what blues-boppin’ sports they really are and the younger ones all go for slick, shiny shark-skin suits with the continental cut, the kind Elvis Costello and Huey Lewis wear, and maybe a pair of Blues Brothers shades, Ray-Bans or something, to pay tribute to their roots…but as far as the long, broad, wide, wi-i-i-de polyester collar with the points spread-eagled outward for maximum aerodynamic lift—or the pimp sox either—they just can’t bring themselves to do it. There are sacrifices, and then there’s suffering—real suffering. Serves somebody else right to suffer.

Hooker may have been the toast of Detroit when he drifted in during the mid-40s, but he supported his celebrity by sweeping factory floors and swabbing urinals. A fellow named Elmer Barbara caught his act in one of Hastings Street’s jumping little clubs and set about managing him, taking him into a little half-ass studio in back of the record store Barbara and his partner, Joe Von Battle, owned. Over the next few years—three years at least, and maybe as many as five– they had Hooker cut everything he knew and anything else he could fake. They knew they had something, but what they didn’t have was the ways and means to put any of it out.

“And one day,” Hooker says, and then says it again with all the emphasis a significant moment deserves: “Then… one… day… he took me over to meet Bernie Besman.” Besman was another local operator, with a small-time record distribution business and an even smaller-time label of his own. “When he heard me, he said ‘I never heard anything like it before.’ He said ‘You got a ahnusual style, nobody got a style like you.’ ” And nearly 40 years later, Hooker can’t help but agree: “Well, it ain’t nobody got a style like John Lee Hooker. I got my style all to myself.” No brag, just fact—Hooker’s style is style, the blood essence of style, a style so strong and so fiercely established in the self that there’s no more chance of another man copying his sound than there is of trying to steal his heartbeat. And nobody knows that better than John Lee Hooker himself.

Besman knew it too, and he took Hooker into his studio. “My first record, which Elmer Barbara already had down, was a big, big hit.” “Boogie Chillen” was an earth-moving stomp, raw and reckless, recalling the unleashed exultation of the night Johnny Lee was in bed and heard Papa tell Mama:

Let that boy boogie-woogie

It’s in him and it got to come out!

“Which Bernie Besman tried to claim, you know, he helped me do that. He didn’t. He got his name on all my stuff, everything that he did, he had his name on my stuff, said that he helped write it. Which was untrue. He couldn’t write the first line of blues—not a Jew can’t! He’s a Jew—a Jew can’t write no blues!”

Turned loose at last, “Boogie Chillen” marked the beginning of Hooker’s recording career. It carved John Lee Hooker’s first notch on the history of the blues, provided a place for him at the table in the Valhalla of blues immortals. More important, it made him a living. It was a solid sender, a jukebox essential in every black bar—down-home and antiquated and uptown, electrified modern in the same moment. It made him a living by making his name. He set his broom aside. “And the next one that came out was ‘In the Mood,’ and it was a big, big hit. ‘Hobo Blues’— it was a big, big hit. ‘Crawling King Snake—it hit off for me. You might remember some of those numbers,” he says with something like modesty. “You wa’n’t around then, but you know.”

A young man in his early 30s, he’d made his name and he was hot. So hot, in fact, that just one John Lee Hooker wasn’t enough to go around. And since his sound was so dead simple and dose to the bone that nobody could seem to steal it, his own voice became his only competitor. Barbara and Von Battle had their stockpile of unreleased tunes, and Besman had connections to a lot of little labels that were paying cash money for a steady jukebox hit. Under contract already to Besman’s Sensation label and licensed to L.A.’s Modern, Hooker’s material began showing up on other companies’ records, featuring rough approximations of his name: John Lee Booker, John Lee Cooker, John Lee, Johnny Lee, Sir John Lee Hooker, Delta John, Texas Slim, The Boogie Man, even Birmingham Sam & His Magic Guitar. The authors of scholarly liner notes used to scold him for the intolerable inconsistencies this created in their alphabetized record collections, but he was shortsightedly intent on eating, and failed to consider the longer historical view.

By the late ’50s, the blues business shriveled as record labels and dub owners reaped the more munificent rewards of rock ‘n’ roll and R&B. Times toughened for bluesmen everywhere, and even from the top of the blues heap it looked like a short step back to pushing the broom. Then, first in England and Europe and finally in the United States, the “folk music” boom occurred.

Gathered together near college campuses, with their tastes formed around a prim, puritan disdain for pop, folk music aficionados were desperate for authenticity, a commodity found in its purest form in the country blues on records made 30 years before. Authenticity could also be squeezed from recently rediscovered antique rural bluesmen who were found not in dusty thrift shops like the treasured records but on daring scholarly search-and-employ missions to the segregated South. Blues researchers would return to Cambridge like triumphant archaeologists just back from crypt-kicking amongst the withered mummies of Egypt, bearing contracts autographed by elderly black gentlemen who might not have actually played any music, authentic or otherwise, in the last decade or two but who were only too willing to throw down the harness traces for a three-figure folk festival paycheck that was more than they’d net from a couple of successful years of sharecropping. And unlike folk music, a check’s authenticity can be confirmed by a bank.

Real folk authenticity was not found, it goes without saying, coming out of an electric guitar amp. When Muddy Waters first went to England in the late ’50s, blues fans were simply appalled at his amplified sound and at the lack of venerable blues standards in his repertoire as well. Hooker’s label at the time, a black-owned company which had the temerity to try him with such folk-curdling abominations as saxophones and the very young Vandellas; made a brief trade with an uptown jazz label, and Hooker was at last recorded as the authentic folk artiste the aficionados were sure was buried inside him. “All commercial restrictions were lifted,” quoth one set of liner notes, and, just to make sure, his electric guitar was too. Hooker, in no economic position to quibble, dutifully took up the acoustic guitar again and combed his memory for suitable old folk-blues favorites such as Charlie Patton’s “Pony Blues” or “Pea Vine Blues” or Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Match Box Blues” or Sonny Boy Williamson’s “Good Morning, Little School Girl”—all those orderly 12-bar rarities that drove the folkies into ecstatic bursts of authentic academic footnotes. Didn’t matter if Hooker hadn’t actually seen one in 25 years or so—if that’s what the audiences wanted to pay for, he could sing about the back half of an old gray mule too. He made sure he got one of those “arrangements of traditional material by John Lee Hooker” copyrights on any recordings he did of any tunes that weren’t nailed down tight, and he managed to slip a few current songs of his own in when nobody was watching too closely. He also had, in live performances down at the old coffeehouse, an unfortunate tendency to backslide toward his electric guitar—though, as a family man with bills to pay, he usually kept the volume turned tastefully down in deference to the delicate sensibilities of his authentic overseers.

“Nothing but the best and later for the garbage.” It’s a fairly famous little motto, the kind of uncompromising slogan guys in white blues bands like to mumble manfully into the microphone between songs, or put on the back of their debut albums. John Lee Hooker said it first, on an album he made with the white blues band Canned Heat in 1970 called Hooker ‘n Heat. Much of Canned Heat’s career had been formed around the irresistible “Boogie Chillen” riff—one of their albums had featured a tune called “Boogie Music” and a 40-minute-long “Refried Boogie,” not to mention a 20-minute psychedelic spectacular entitled “Parthenogenesis.” In the wake of their appearance at Woodstock, they decided to share their success—either that, or to gather some desperately needed credibility—by introducing John Lee Hooker to yet another generation of white kids.

There were two singers in Canned Heat, a curious set of bookends. Alan “Blind Owl” Wilson (they all gave themselves real blues guy nicknames, although, it being the hippie era, one of them chose “Sunflower”) was a nearsighted young man with Coke-bottle glasses and an inclination toward scholarly pursuits in the blues field; Bob “The Bear” Hite was big and sloppy, and he had a truly heavyweight record collection. When Hite sang, he lost all control over the pronunciation of the letter R: “Sun gonna shine, lawd, in mah back do’ someday.” Wilson, on the other hand, was so determined not to act the shoe polish–smeared fool that he sang his blues with nearly all the usual rollin’ and tumblin’ Gs completely restored—he even filled in a fair share of Hite’s missing Rs.

By the time Hooker ‘n Heat was released Wilson was dead—blues-riddled victim of a scholarly inclination toward heroin. He had played remarkably acute harmonica and piano and guitar behind Hooker at the recording session—the whole band, in fact, had out-done themselves in decorous behavior, leaving Hooker almost half the album to himself, something almost unheard of on these sons-fathers occasions so beloved of the white blues boys. (A decade later, when Canned Heat had nearly been forgotten, a second volume of Hooker ‘n Heat had trouble finding any room for Hooker at all.) In Wilson’s dearly departed absence, Hite handled the liner notes. “He arrived for the session,” Hite wrote of Hooker, “wearing a plaid cap, leather jacket, black satin shirt and some old dress slacks and carrying the Epiphone guitar that had been around the world more than once. Once at the studio we tried out about eight really ancient amps before finding the one that had that real ‘Hooker’ sound—a sound we hadn’t heard on John’s records for a long, long time. We built a plywood platform for John to sit on while he played. An old Silvertone amp rested a few feet away.” For Hite, the key word wasn’t “drifting” but “old”; amplification was authentic now, although it helped it the amp was, like the bluesman, ancient.

Hite was Hooker ‘n Heat’s co-producer and the little scrap of studio chatter that includes Hooker’s now-famous motto sheds something like light on the ways of white blues scholar-producer-entrepreneur-fans and the ways John Lee Hooker had learned to deal around them. Hooker is saying:

“We got about 10 [songs] there now. You know, like I told you, don’t take me no three days to do no album, er-um…”

Hite: “We’ll go for a triple album!”

Hooker: “You go for a triple album, you gonna go for triple money.” (Laughs.)

Hite: “We got lots of money. This is a hit album—don’t worry about that money, it’ll come rollin’ in.” It’s a carefree phrase that echoes through the ages, spoken who knows how many million white times, etched into how many million black minds: “Don’t worry about that money…”

Hooker (no longer laughing but serious as death): “You got to worry about that now. Nothin’ but the best and later for the garbage.”

Hite: “What’s that?”

Hooker: “Natural facts.”

The song that follows is “Burning Hell,” and it’s attributed to the songwriting team of John Lee Hooker and Bernard Besman, although it was recorded by the wayward preacher, bluesman, and murderer Son House long before Hooker and Besman ever linked up. Little matter—if Hooker didn’t write it, he’s long since made its terrible defiance his own, all his own. “Ain’t no heaven,” he declares, “Ain’t no burnin’ hell / When I die / Where I go / Nobody know.” He went down to the churchhouse to see the preacher, and he got down on his bendin’ knees, and he prayed, he prayed, he prayed all night. He begged the preacher to pray for him but no—ain’t no heaven, ain’t no burnin’ hell. The song has stopped being anything like a song and turned into a furious stomping rant, a screed against all chance of salvation: “Ain’t no heaven,” he spits, “Ain’t no burnin’ hell.”

“Burning Hell” is a life-or-death burst of existentialism from someone who’d most likely never heard that word, a desperate and cold-blooded denial of even the remotest possibility of comfort for any of us, in this world or the next. It came not from a walleyed French philosopher but from a black man who’d painted himself into a terrifying corner. The line between the blues and gospel may have been thin, but it was indelible. A bluesman had surely surrendered himself to the music of the devil, and there was no place for him among the saved. “Ain’t no heaven,” Hooker insists frantically, angrily, scornfully, fearfully, “Ain’t no heaven / knit no burnin’ hell/ Hey, hey / Hey, hey/ Hey, hey/ Pray for me / I don’t believe / I don’t believe.” He’s smacking his guitar, his foot pounds like hollow doom. He knows his own prayers aren’t worth a damn, and his soul—if he even has one—is as good as lost. And behind him on harmonica, eyes closed behind thick lenses, Alan Wilson, not long for this world, is scrambling to keep up.

John Lee Hooker has two sons—two real sons of his own. Junior, John Lee Hooker, Jr., is a singer too, and sometimes opens his father’s shows. “He’s a good MC—he’s a talker, a good singer.” But it’s his other son who brings the light to his eyes. “Yeah, I got a son, he’s one of the best organ players in the world—Robert, he’s younger than Junior. Man, he can sound just like Jimmy Smith or anybody he want to. And just as good on piano. He never got spoiled like, er-uh, Junior was. He used to go with me on tour and be my organ player. Robert was about seventeen or eighteen—he couldn’t drink, but they would let him come in and play. He was go-o-od!” There’s a pause. “But now he in the church now.” Hooker goes silent, goes back to looking at the ball game on TV, buttoning another button of his red dress shirt.

In the dead silence, oddly enough, the polyester problem rises again. Because when you think about it, about the obsessive urge the white blues guys have to ape every riff and lick and gesture their black blues elders lay down, to duplicate all the degradations and to follow their soulful idols right down to the very depths of hell—just so long as it doesn’t mean wearing a polyester suit with a wide collar—well, it starts to make some sorrowful sense. Because with most all of the white blues guys, if they were really and truly willing to go all the way, why, somewhere back deep in their dad’s own suburban closet is a polyester suit, still hanging there nice and fresh and preserved—this stuff lasts forever, with no biodegradation taking the snappy crease out of your cuff—that’s practically the spittin’ image, the precise spiritual twin of, say, Muddy Waters’s own stage and street wardrobe. But what white blues guy wants to dress like his dad? Hey, the whole reason that white guys get into the blues is for the sake of the rebellion that the blues represents. Or at least the tradition-smashing rebellion it represents to white guys, who do their best not to see their heroes’ polyester suits and pimp sox and F-15 shirt collars as an expression of a desperate need to be accepted, who do their best not to see any of that at all.

On the television in the room high above the beach at Santa Monica, one of the Dodgers has just hit a home run with one man on, and John Lee Hooker is in an expansive mood. He’s laid down a few choruses of the Standard Rap, and in the absence of questions aimed at clearing up his muddled discography once and for all, he gets going on a subject that’s very near and dear to his heart—money.

“I makes pretty good money and I keeps my overhead down. And I’m always tryin’ to come along with my earnings. Year after year, I been buildin’ it, my income. I ain’t aimin’ to blow it with women, whiskey, cocaine. I own four houses. I own two in Oakland—one, two, three in Oakland—and the house I’m livin’ in in Redwood City. I budgets myself. I got myself a real nice home and two real nice cars. I got myself a 380 SL Mercedes, a ’82, and I got a Seville, a ’81 Seville.” He’s proud of himself, and even prouder when he says, “I ain’t had a day job since I got a hit with ‘Boogie Chillen.’”

It’s sad to hear Hooker’s rendition of the way his life is lived these days, and if word of it ever gets out there’ll almost certainly be a radical reappraisal and an inevitable downgrading of his aesthetic importance among the more tough-minded of the blues journals. First of all, he failed to die a mysterious or painful or illicit or degrading death at a young age, and thus leave his promise sadly unfulfilled. It was a major mistake, historically speaking, and he’s compounded that error by the utterly unromantic bourgeois banality of his unbecoming, prosperous survival. The legend-making process that brings the blues to vicarious life for its white audience has been short-circuited entirely by Hooker’s hard-headed refusal to cooperate. The best he can do is describe his social life off the road, which starts off as something of an improvement but rapidly turns repulsively upscale.

“I go into these little bars, the down-home bars—I don’t need to spend a lot of dough, show off, go to these places where a bottle of beer costs you a couple of dollars. That’s just the way I am.” He hesitates. “When I go to some of these places, you know what I do? Maybe this sounds silly to you, but I get some guy, you know, give him ten or fifteen bucks when I’m driving my Mercedes, and I says, ‘Watch my car, keep an eye on my car till I get ready to go.’ Oh, I got a burglar alarm on it, but some of these places, a burglar ‘larm don’t mean nothin’. I’d rather be out $15 than be out a whole car—oh, I can get it back, the insurance gonna have to fix it, but I gotta pay the first $500—I got a high reduction. With everything on that car, I paid $46,000 for it just like it was. Then I had the telephone put in there—that was five thousand. That $51,000 right there. Then I took off the wheels that come with it and got those steel wire wheels? Put those wires on it—might as well go all the way, you know?”

It’s almost too depressing to go on. Cadillacs, Mercedes, wire wheels, mobile phones—surely Blind Lemon Jefferson and Charlie Patton would never… or would they? It’s enough to cause a blues fan to go find some other kind of music to patronize. But Hooker’s too busy to consider the dreadful blow it might provide to his authenticity if word should leak out. “It’s kind of expensive to use. I don’t use it all the time, just once in a while, like when I want to kind of show off—see some ladies, you know.” He laughs. “Sometimes you can fake with it. You drivin’ along, ‘tend you talkin’ on it while some pretty lady’s drivin’ along by. You pass somewhere where a lot of ladies is at, ride all along in that area. They see the phone, they see your mouth—you talkin’ your mouth. They don’t know whether you talkin’ or not.” He laughs. “They say [falsetto], ‘Ooooh, looka that! Looka that!’ ” He’s slapping his knees now. “Yes sir! Yeah, it’s a lotta ways you can do that, you know. Yeah, it’s a lotta ways you can do that.”

There’s another story that John Lee Hooker tells, strung loosely through the song he sings. It drifts, it rambles, it stumbles and stutters and shouts, it walks a bad, bad walk—it talks that talk. A boy comes up from the country. Drifting. He goes from corner to corner, bar to bar, town to town, woman to woman. Drifting and drifting, like a ship out on the sea. Words fall out of him—strong words—and he piles them up into songs that are stories, and stories that are songs. Some of those words and some of those songs come from someone else, someone who came along before him, but they belong to him now, because he makes them his own. He doesn’t sound much like anyone else, and that’s not necessarily the way a young and hungry man would want it, but that’s the way it is. The songs he sings are his, but they belong to anyone who flips a coin at him too.

Sometimes he feels so good, so fine. The style he’s got, ain’t nobody else in the world has got it, and can’t nobody take it away. It’s his because it comes from him, and because he knows who he is. His songs piss and moan, slam the door, kiss your ass goodbye. They wheedle and needle, they feel sorry for themselves, they laugh right in your face. They hold you ‘neath the black water till the little bubbles stop coming up. They rave and plead and beg forgiveness, they set back and watch. He knows who he is.

“There ain’t no coffeehouses anymore,” Hooker says, but the place he’ll play this evening is about as much of one as you’re going to be able to find these days—it serves fruit juice. The audience is mostly white and mostly reverent. Mostly. He comes out adorably, a small man getting smaller with age—and stiffer in the joints—wearing his white fedora and his sharp red suit. He’s making a solo appearance tonight, but his guitar is plugged into an amp and the air fills with ragged, jagged riffs, rough, raw, lumpy, coagulated clots of rhythm. He does a few of his hits and a few other things, and the audience feels called upon to demand the boogie, to offer John Lee Hooker yet another piece of artistic advice.

“I’m’na dedicate myself a number,” he says ever so slowly, his voice so rich it must make God jealous. “And I hope you like it.” It doesn’t sound like he much cares one way or the other. “It’s called ‘I Cover the Waterfront.’ It’s a easygoin’ ballad, easy on the ears. Slow.” He pauses. “But true.” He’s thumbing the strings of his guitar as slowly as he talks. “Take a listen.”

The song is full of space, empty space, and his voice. It’s blank, unrhymed imagery, as so many of his most personal songs are, and no song has ever been lonelier. He’s walking the waterfront, watching for the ship that brings her back. Watching. He sees other people meeting their loved ones, hugging and kissing, but he doesn’t see the one he’s waiting for. “And the ships / Headed out / For their next destination / I still sit there / Coverin’ the waterfront.” And then the guitar speaks—and as it does, a drunk white kid up front gives out with a good-time party holler, too antsy to wait for the boogie any longer.

“Be quiet,” John Lee Hooker says softly.