“I feel as though I’ve had a really blessed run with some great people. I wouldn’t ask for anything more than I’ve had.”

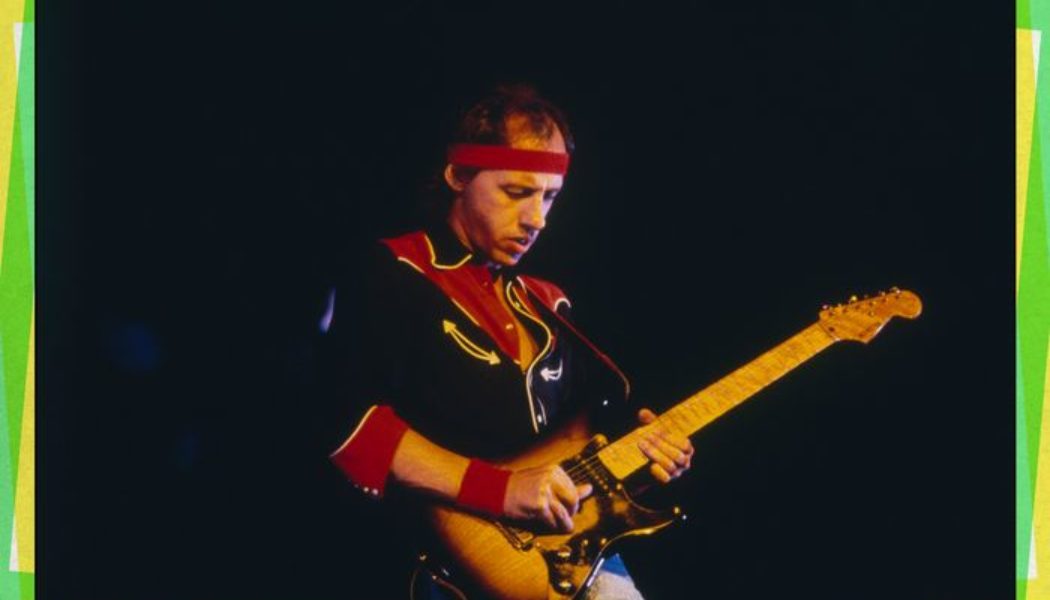

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Bill Marino/Sygma via Getty Images

Mark Knopfler is a tough guy to pin down. A reluctant sultan of swing, if you will. Fame? He can’t think of anything good about it; in fact, he eschews it instinctively. But he’s been in its shadow since Dire Straits debuted their self-titled album of lyrical portraits in 1978 — he was their sole songwriter and de facto leader until their breakup in the early ’90s — cementing it further with 1985’s epochal Brothers in Arms and a steady collection of solo outings in the subsequent decades.

Knopfler’s lineage now includes One Deep River (out April 12), an elegant record that’s a culmination of everything we know and admire about his style. “I’m always thinking about another crowd, another arena, another place, another time,” he tells me, “and another reality.” This type of geographical osmosis is at the core of Knopfler’s work, which has reverence for the past as much as the future. His rich, fluid guitar playing is just an added bonus. But if you try to compliment him on it, you might be met with a laugh: “I didn’t know what I was doing. At least I was there.”

If you were to look at the last tour set, it would be anything that was still part of the picture. “Brothers in Arms” or “Romeo and Juliet” perhaps. “Sailing to Philadelphia.” They survived the trip. It’s quite nice to be able to go on playing those songs because you’ve written them and they mean a lot to people. So I don’t just skate over them; I try to find something in there that’s new and interesting. You try to get the most out of songs and they take a lot of playing. If you try, the song will try, too. Surely you never know if you will survive the trip. When you set out to write something, you never say to yourself, “Oh, this is going to be good all the way.” Nobody knows that. It’s like a love affair. You don’t know, for sure, where it’s going. I’ve been lucky a few times and had some things that stuck.

Another part of the fun is touring, which I’ve got to contemplate now as being something that’s over and done with. But I’m not scared of that, I’m quite happy about it, because what it means is that I’ll have more time to write. The first stage was getting used to having a guitar and then getting used to the idea that maybe I could play a little bit as a guitarist. And then, getting used to the idea that maybe I could write a song. And then thinking of myself as a songwriter is probably the last thing. I’m still adjusting to that and what I’m hoping to be able to do is write a couple of good songs before I quit.

There are definitely some that hang around in the junkyard out the back in bits, and before you can make them into a finished thing, they take their old time. One song took 16 years. Other songs can take 16 minutes. It took a long time for “Rüdiger” to arrive because I wrote the lyrics without changing a word right after John Lennon was assassinated. I wrote about an autograph hunter, “Rüdiger stands in the rain and the snow.” We went to Germany and that’s where I saw him, met him, and I was obviously thinking about the shooting in New York City. But for the music to arrive good and ready, it took years. In my case, there doesn’t seem to be a hard-and-fast rule about that stuff, and I never panic about it because I know it’ll turn up eventually.

That’s what it’s like, certainly, for a boy who’s got the scrapyard of a mind that I have. You find that you know certain things about boy things — like bicycle badges, just useless information. You have things in your head that stay there until you need them. And then you come out with this useless stuff occasionally. It’s kind of general knowledge, I suppose. I have a friend and we just sit and quiz each other on music and rock-and-roll records. We take enormous winnings off each other, which are all forgotten about as soon as we start playing. We give each other clues if someone’s struggling, but it’s great fun. It’s amazing how much rubbish a mind can retain, isn’t it?

I think we’d probably be making up a spoof song about somebody or just having a laugh and taking ideas from the floor. It wouldn’t have been anything serious. Writing, for me, is a solo affair and I never could write in a recording studio. Now I’ve got a studio of my own and I can’t write in it either. Go figure. I like recording studios for recording purposes only. I would write on the road and I would write in hotel rooms. What I’m looking forward to is having more time to write at home and seeing what happens there, just trying to write like a writer instead of snatching the moments here and there or late at night. It feels more civilized to me. In a hotel, you might see me walking down a corridor carrying a chair with no arms because there’s not one in my room, so I’ve found a dining chair somewhere and I’m bringing it back so I can put it at the desk and work on a song.

I haven’t had the chance to think about it, so I’m sure I’ll be wrong. But I quite like the optimist in Jeremiah Dixon from “Sailing to Philadelphia,” as opposed to Mason’s pessimism and apprehensiveness. Mason seemed to have this fear about the enormity of where they were in this vast unknown wilderness of savages and what was going to happen to them. Whereas, Jeremiah would have a glass of wine with the ladies quite happily and just get on with the business of mapping out the Mason-Dixon Line. You identify with certain characters more than others — you just like them more. I think that happens to authors, because things you create do tend to start going their own way. Certainly a song does. When you’ve written a song, the song just says, “Well, see you,” and goes off down the road, just like a little figure you’ve created. When you have children, you realize it’s quite similar to that in some ways. There’s something enormous about it.

I find that I don’t have to love these characters. In fact, sometimes it can be the opposite. They can kind of scare you as well. They can be somebody whom you actively disagree with, or they can be somebody different from how you think you are. I’m not saying I’m in that Randy Newman bag. I mean, I’ve worked with Randy, adore him, and love his songs, but I’ve become much more interested in his direct, soulful style rather than identifying with some horrible individual. It’s great the way Randy could do that — you could identify with a war criminal, write about a war criminal, and try to understand what it’s like to be that. I wrote about a character like that for Dire Straits in “The Man’s Too Strong.” That’s the only time I’ve done it. I don’t think I could write a song as an executioner now. I don’t think it would interest me. I’d rather be able to write a song like “You Are My Sunshine.” To me, it would be in many ways superior. Take “Nobody’s Darling but Mine,” by Merle Haggard. I’m busy, unsuccessfully, trying to create something like that.

In certain places you feel the ghosts. When I’m in Edinburgh, say, it’s a historic town, and a lot of my ancestors are Scottish so you feel them. The songs you sang when you were a kid, the scraps of those come back to life in your soul. History is in the cobblestones. When I’m in Rome playing at an arena, I feel it, like I’m playing the part of the gladiator. You connect with the place in a real geographical sense. I’m there from centuries before. Sometimes I’ll think of what places were, like with “Telegraph Road.” I’m thinking about what it was like when it was a little path going along the lake shore in Michigan, once upon a time. And now it’s 12 lanes of Texaco.

So it’s a different reality, but I like thinking of all of those realities at once, together. When “Sailing to Philadelphia,” came to me, I was reading Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon, but I was looking down on this modern accommodation of massive highways, chemical refineries, and big ships in the canals — thinking only in the blink of an eye, a few years ago, Mason and Dixon were getting barges out from the United Kingdom to this deserted place. There was hardly anything there. Now, it’s Philadelphia, and that all seems to have happened in a very short space of time. Then you start wondering what it’s going to be like in another 100 years. I’m always imagining a place in another time — either the way it used to be, the way it is now, or where it’s going and what it’s going to. I don’t know whether I can help it. I’m sure a lot of people do it. Because, also, America is such an evocative country. The language of it, the biblical references, the places, and the names. I get enchanted just reading lists of kids’ names from the South. It’s the promise of those names. The promise is always there, isn’t it?

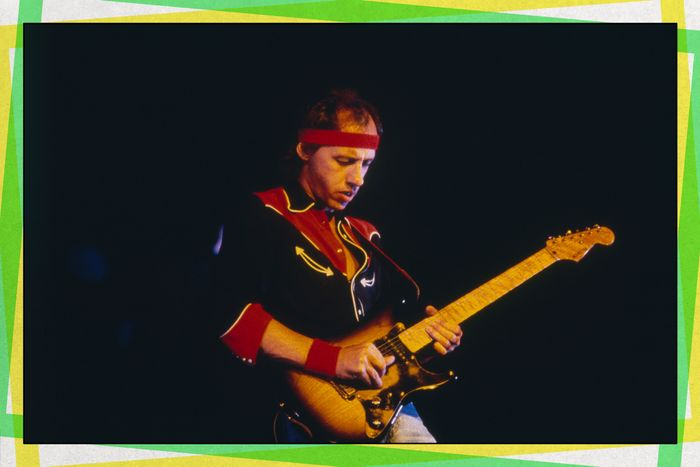

The sultan of swing with the band over the years. Clockwise from left: Photo: Rob Verhorst/RedfernsPhoto: Rob Verhorst/RedfernsPhoto: Rob Verhorst/Redferns

The sultan of swing with the band over the years. From top: Photo: Rob Verhorst/RedfernsPhoto: Rob Verhorst/RedfernsPhoto: Rob Verhorst/Redferns

There are certain songs that go with playing live. Playing “Going Home” at the end of a set, to a crowd anywhere in the world, people go bananas. It’s a fun thing for a band to experience. I suppose you get used to that happening, the big audience reactions and massive noises. It’s a thrill. “Wow, this is Madison Square Garden and people are going nuts.” Surely, that’s what you’re doing here. Otherwise, go home. It doesn’t mean anything to you. You’re in the wrong place. You got to want to be there and you’ve got to go looking for the source of it. So you become this little dragon slayer who’s got a nerve. Who do you think you are? You’re just a kid who doesn’t know anything, but without that, where would we be? I’m perfectly well aware that a lot of it is just blowing smoke. But you’re trying to figure out a way through. You stick around for long enough and after a while you get a bit more of an idea. I feel as though I’ve had a really blessed run with some great people. I wouldn’t ask for anything more than I’ve had.

Some of the guitars are pretty hard to play. Playing the beginning of “Telegraph Road” always seems hard when you’re going from a spiffy electric to that old war horse. You’ve just got to brace your hands for an old guitar from the 1930s. So that’s all part of the challenge of that song, when the guitar itself doesn’t want to play pretty.

Learning to play those longer songs in different conditions — or shorter songs we extended for a live setting — before the modern lights came in was difficult. They got rid of the big old heavy lights, because if one of those dropped and hit you, you’re a dead person. And the new lights seem as though they don’t generate any heat at all. The old lights generated so much heat. We were always drenched when we came off-stage, literally soaked to the skin. Sweat would be stinging your eyes, so you learn to play with your eyes squeezed shut. I’m pretty sure I played a lot of that stuff without looking. That’s all part of the fun of it: figuring out ways around things. I remember someone putting a little note up at the front row that said, “More liquid gumption, please.” I was spraying the audience with so much sweat that it was stinging them. I always used to think, Only rock and roll could do this.

It was very different from the way that I work. I was really pleased to have gotten to be there in the first place. I certainly wasn’t expecting to walk out at the end of that day and have anything on the record that they would keep. The story that I got from Gaucho’s engineer was something like, “Man, you ought to see the guys crawling out of this place,” so I didn’t expect to emerge victorious at all. I’d gone through this period of loving Steely Dan records. I just heard “Any Major Dude Will Tell You” the other day. What a beautiful, beautiful thing. The music ends up affecting you and becomes part of what you are.

I think it’s easy to forget what that little chord sequence in “Time Out of Mind” means to so many people. You know, what living they’ve done with it or how they’ve used it to live. I must have played those chords a thousand times in the studio. What’s important is to try to get into the mind-set where you’re not thinking of that — you’re thinking of what it means. If you’re, for example, playing “Brothers in Arms” in a great big stadium in Munich where Adolf Hitler spoke, it invests it with something. So you’re thinking about history and where we are now, where we’re going, and where we’ve been. You get that historical perspective and it gives you all of these other perspectives, which I don’t think you can put a price on.

One sample stanza for reference: “I have legalized robbery, called it belief. I have run with the money

I have a-hid like a thief.”

Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, impressed by Knopfler’s unique guitar sound on Dire Straits’ debut album, recruited him to play on the Gaucho track “Time Out of Mind.” The opening and mid-song solos are all him.