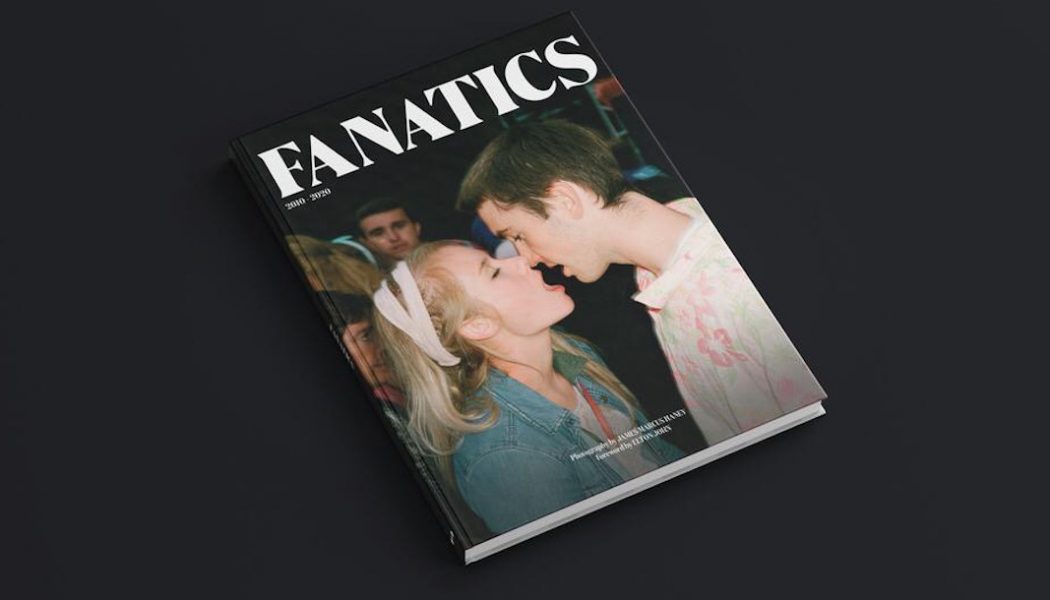

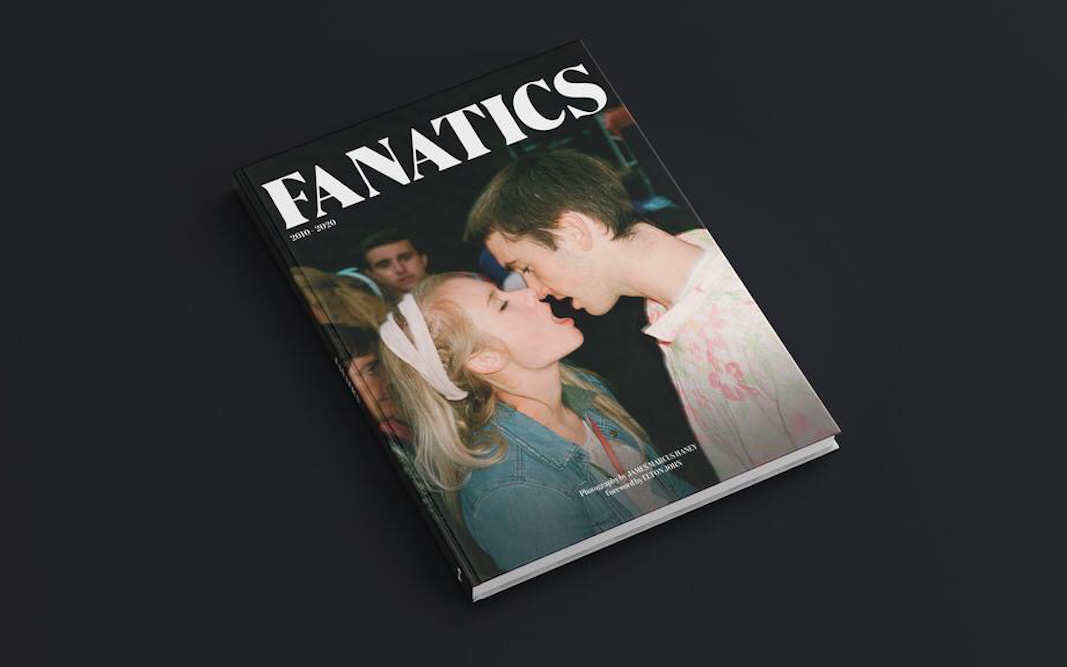

The cover of James Marcus Haney’s new photo book, Fantatics, doesn’t feature a massive arena crowd or rowdy mosh pit — any of the obvious concert imagery one might expect. Instead, it shows two people mid-kiss: eyes largely closed, mouths agape, seemingly transfixed amid a sea of strangers.

Haney has “no idea” who they are.

“I took one photograph of them, and I don’t think they even registered that a photograph was taken,” he tells SPIN with a laugh. “I hope they are together and married with kids or something. If they see themselves on a bookshelf somewhere, I hope that’s a good thing.”

In this case, the image illuminated Haney’s purpose for the book: documenting the personal — and often intimate — side of the concert experience from 2010 through the early pandemic. “Right from the bat, I wanted to get across that we’re tapping into the personal journey of a fan, that it’s not just photographs of crowds,” he says. “At the heart of it, it’s a really human book. It’s kind of a like a time capsule of the last decade through a music filter.”

Fanatics weaves in personal reflections from artists he’s toured with during that time, including Coldplay’s Chris Martin, Metallica’s Lars Ulrich, the Strokes’ Albert Hammond Jr. and Mumford & Sons’ Marcus Mumford, all of whom contributed to Haney’s own profound, illogical and hilariously wild ride to a photography and filmmaking career.

While attending USC film school in Los Angeles, Haney often posed as a press photographer — using one of the college’s cameras — and snuck into music festivals. He made a short documentary of his experiences at Coachella and Bonnaroo, and he later handed a burned DVD of that film to a Mumford & Sons roadie, who then passed it to the band. They liked what they saw. And with two weeks until his final exams, he took a liberating leap: leaving school to join that group on the Railroad Revival Tour with Edward Sharpe & the Magnetic Zeros and Old Crow Medicine Show.

But Fanatics is bigger than Haney’s own story, examining the transformative experience of live music from multiple angles: the photographer, the band and the fan. And it also, sadly, serves as an obituary for the concert as we once knew it, before face masks, COVID-19 tests, drive-in experiments and living room livestreams.

“It touches on something we took for granted,” Haney says. “Music is such a big part of my life, as a fan and in a working capacity. And going to a show was such a normal thing — getting stuck in the middle of a crowd was such a normal thing. It’s only when something so normal is taken away that you realize how formative and special and now seemingly unique it was. I look at the photos, and it’s like, ‘Oh, my goodness. I can’t believe we were [that close], mixing sweat with people we’ve never met in the middle of a mosh pit and making out with strangers.’ That sounds ludicrous now. It sounds crazy! I hope people see it as something to look forward to when we do get back to live music.”

Haney spoke to SPIN about his winding career, the eventual return of live music and the bittersweet beauty of waiting for a festival port-a-potty in the blazing sun.

SPIN: Obviously the timing of this book is crazy — we don’t have concerts, and you’re releasing a book that glorifies the entire concert experience. It actually makes me sad looking at some of these images.

James Marcus Haney: It’s definitely crazy timing, and it’s not something like, “Oh, now’s the time to put it out.” I’ve been trying to get the book out for the past couple years, but it’s always been on the back burner. I’d work on it a little bit here and there. It wasn’t until the end of last year before we knew we’d be in a pandemic, that we started finalizing the design and moving to printing. For a long time, I was bummed that I was never getting around to putting this book out. But the timing worked out really nice because it’s such a weird turning of chapters, obviously. Because this book spans the last decade — the decade ends with the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic — the [final] bookend is the complete lack of what this book is about.

It really hit me looking at these photos: I miss everything about shows — even things I once considered mundane or even frustrating. I look back nostalgically on overpriced food and long bathroom lines. Do you feel that way?

Absolutely. Especially at music festivals — half the time you’re miserable. It’s too hot or the bathroom line is long, and you get in there and it reeks and you don’t want to touch anything. You’re 10 miles away from your car, and you’re exhausted and hungover. Half the time you’re like, “Why the hell did we pay money to do this?” But two days later, all you remember are the incredible highlights: those moments with your friends and seeing your favorite band, the culmination of these songs and what they mean to you in a place with 80,000 [strangers] who will never be together again. In the book, I tried to celebrate both sides of that experience. But yes, I would absolutely go sit in a stinky port-a-potty right now if I could go out and crowd-surf right after.

One amazing shot from the book is your friend crowdsurfing in a wheelchair. Tell us the context of that one.

That was at Outside Lands, and I believe it was in 2013. That guy is my best friend, Ryan Chen. He and I went to high school together, and he snuck into shows with me all over the world. At that particular show, I was on stage with Young the Giant, shooting for them. I look out, and there’s motherfucking Ryan doing his thing, crowdsurfing. I’ve been in the crowd him at Kendrick Lamar shows where we’ll crowd surf him. [At one show], Kendrick stopped in the middle of “Alright’” and shouted out Ryan: “This kid right here is showing us all…” And then went right back into “We gonna be alright.” The whole place just lost it. It was so powerful.

In the book, Sameer [Gadhia], the lead singer of Young the Giant, writes about the moment he saw Ryan crowdsurfing for the first time, which was back when they were had their first record and that single “My Body.” Ryan was crowdsurfing during that song. The lyrics are, “My body tells me no / But I won’t quit; ’cause I want more.” Sameer writes about how, for the first time, he knew what that song — that he wrote — was about, when he saw Ryan crowdsurfing at that show.

It’s super powerful for me because Ryan is one of my dearest friends. He was our cross-country star in high school — he took us to nationals and was an all-around athlete. In college, he had a snowboarding accident and broke his back. But he snuck into all the concerts with me. He’s an amazing dude. I put a film out in 2014 called No Cameras Allowed, which is all the footage I shot while sneaking into music festivals. Ryan’s a big part of that film. It documents our journey, and those photos were taken all along that adventure.

Do you ever think about the other version of your life — the one where you didn’t drop out of school and embark on this insane adventure?

It’s definitely something I’ve thought about. It came down to two weeks left at USC. Had I stayed there, taken the finals, walked at graduation, got my degree and not gone on this train tour across the country, what would life be like? I would hope I’d be doing film and photography, but I certainly wouldn’t have the insane, rich, wild experience of the last 10 years, touring the world many times over with these incredible artists. Professionally it’s been incredible. But on a personal level, it taught me way more than I ever learned at USC film school.

Do you think we’ll ever get to a place where we can feel this free again at a concert? I wonder if we’ll ever feel that sense of community and freedom, where we actually don’t mind bumping up against each other.

To get back to 100% [of that] freedom, no. I don’t think so. I hope we’ll get close. This has been such a gnarly thing for people with such drastic results that I think there will always be reservations. You’re never going to see a crowd without some people with masks on. I think we’ll have moshing again. I think we’ll have arena shows eventually. I do think it’s gonna be a long time before it feels like what it felt like this time last year. I think masks are going to be a part of any crowd shot going forward.

That’s weird to think about — the mask era of concert photography.

The very last photos in the book are of the Palladium and the Satellite, two venues in L.A. They’re both boarded up with marquees that are COVID-related and someone walking by with a mask on. It’s the final bookend to the 2010 decade: the complete lack of what the book is. That is the fan experience now: no one there.