Columnists

Making Kenya’s sugar competitive

Friday December 22 2023

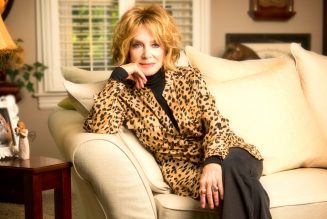

Workers arrange bags of sugar at Mumias Sugar Company’s store. FILE PHOTO | NMG

The sugar sector has a multiplier effect on other industries such as food — -confectionary and beverages. The sector is also a significant contributor to Kenya’s economic growth in terms of employment creation and facilitation of investment.

According the to State Department for Trade, as of 2023, about 8.0 million Kenyans depend on the sugar sector as a source of livelihood. No wonder talking about the operations of the sugar sector in Kenya is emotive.

Before Kenya subscribed to the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) principles and regulations between the 1970s and early 1980s, the country was producing enough sugar for domestic consumption and had a surplus. Kenya had an allocation to export sugar to the European Union (EU) countries.

The government through the Kenya National Trading Cooperation (KNTC) purchased all sugar produced in the country and was responsible for the distribution of sugar.

A sugar section in the Department of Internal Trade was responsible for analysing the sugar markets and would advise when to export sugar and when not to export, to ensure that there was adequate sugar for domestic consumption. There was a high level of order in the sugar sector.

I am not in any way advocating the return of retrogressive trade controls and regulations. Economic liberalisation is healthy for economic development, especially when implemented cautiously. Liberalisation contributes to competition that encourages innovation and creativity which are among key drivers of expansion of trade, investment and enhancement of enterprises’ competitiveness.

The performance of Kenya’s sugar sector started dwindling in the late 1980s and come the year 2002, Kenya had to apply for safeguards from the Common Market for Eastern Southern and Africa (Comesa) member states to protect the industry from cheap sugar imports from the regional trading bloc.

Subsequently, Kenya has been applying for an extension of the sugar safeguard after every expiry of the other — the latest being the one granted in 2023 for a period of two years. At the approval of Kenya’s first application for the safeguard, Comesa member states pronounced directives for improving Kenya’s sugar sector.

Among the directives were the privatisation of the ailing sugar millers, a new method of cane payment based on sucrose content and diversification of cane varieties to increase production and reduce the cost of production. The safeguard measures were intended to enable the country to restructure its domestic sugar sector to attain competitiveness in the region and beyond and be profitable. Some performance improvement has been registered.

According to the Sugar Directorate, the sugar industry in Kenya steadily expanded in 2020. The area under cane increased by 24 percent from 159,288 hectares in 2010 to 197,438 hectares in 2019, in an effort to meet the expanding mill crushing capacities.

During the period from January to June 2020, total sugar production was 298,636 tonnes compared to 244,826 tonnes in the same period in 2019, a 22 percent increase.

The concern is that the seventh extension of sugar safeguard is the last one granted to Kenya. Will the sector be strong enough to compete with the cheap sugar imports from Comesa member states in the next two years from December 2023? I contend that it is possible as long as all the relevant institutions work in a coordinated approach to implement strategies for enhancing competitiveness in the sector.

I share the sentiment of Dr Christopher Onyango, the Director of Trade, Comesa who averred that “there is an emerging shift of consumer preferences, towards healthier diets which has boosted consumer spending on healthy food, more so in leading producers in developed economies.

The excess sugar is likely to be dumped into the region and this should worry all of us given the projected increase in world sugar production in the coming years.”

Dr Onyango listed the following as among the strategies to address emerging uncertainties: the adoption of environmentally sustainable production, infrastructure, trade policy, research and development and unlocking the potential for the production of energy.

This is in addition to addressing productivity and diversifying sources and usage of sugar to help improve the position of small-scale sugar cane growers and their dependent communities, which are undervalued by the global sugar market.

Dr Ogundo (PhD) is a former Secretary of Trade, in the State Department for Trade. She is currently a part-time lecturer at the Co-operative University of Kenya.