The Madison Symphony Orchestra wraps up its 2022-’23 season this weekend with an ambitious program that features two exciting works: Florence Price’s Symphony no. 3, a symphonic masterpiece, and Carl Orff’s “Carmina Burana,” a grandiose showstopper that demands a large ensemble.

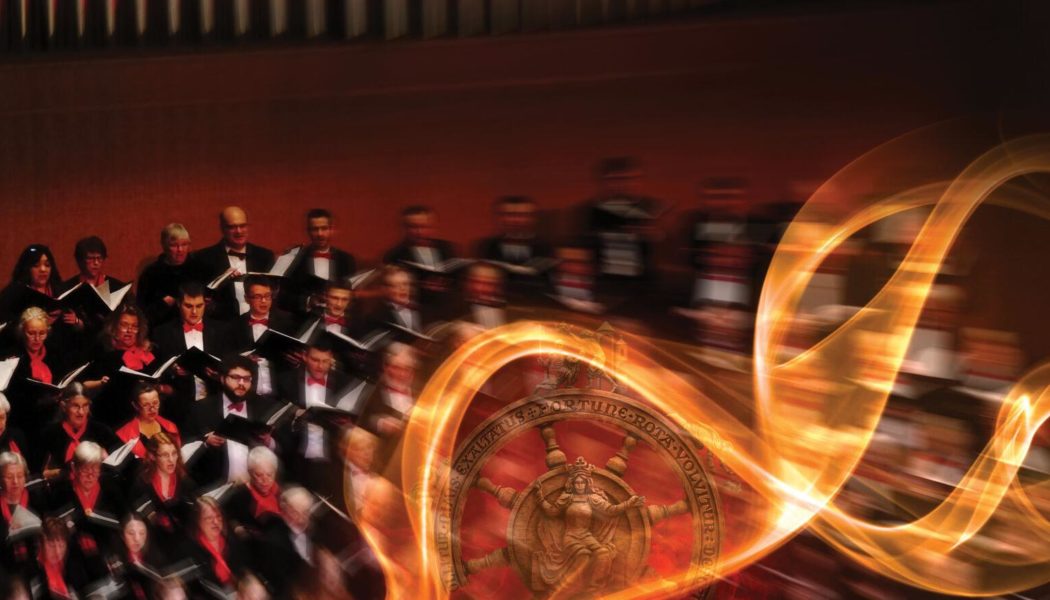

On Friday night, the MSO invited to Overture Hall the Madison Symphony Chorus, the Madison Youth Choirs, and the Madison West High School Choirs, along with soloists Ben Edquist, Jeni Houser, and Justin Kroll. The sheer power of the many musicians performing together was felt from the famous opening “O Fortuna!” to the very end.

Orff considered the work a “secular cantata.” It is a collection of 25 movements, divided into three large sections, “Spring,” “In the Tavern,” and “Court of Love.” All of the work’s text come from the Codex Buranus, a collection of 12th and 13th century poetry that was uncovered in the 19th century.

The MSO performed the piece’s quick tempo changes and dynamic shifts with varied success. During long stretches of repeated eighth notes, the choir often sped up ahead of the orchestra, and during some accelerando sections, the orchestra became loose. Still the MSO established a great balance with the singers and came together for the most dramatic moments of the piece.

Entering for the third “Court of Love” section, soprano Jeni Houser took the stage in a striking red dress, perfectly appropriate for her song texts that included mention of a girl in red and a red rose. During no. 15 “Amor volat undique,” Houser unveiled a gorgeous vibrato that carried beautifully in Overture Hall and in no 21 “In truitina,” Houser mesmerized the audience with her angelic high register.

Although the soprano soloist sang arguably the most beautiful music, the baritone soloist part was the most demanding, but Ben Edquist performed expertly. He displayed great vocal range, especially in no. 16, “Dies, nox et omnia,” and proved a wonderful performer beyond his singing.

More than marking the end of the MSO’s season, this weekend’s concerts mark the final appearances of retiring principle French horn player Linda Kimball after 36 years with the ensemble. Before the second act on Friday night, Maestro John DeMain shared his appreciation for Kimball’s tenure, calling her a “positive force” and a “passionate advocate of the instrument she played.”

Though not as grand a production as the closing piece, the opening work, Price’s Third Symphony, holds a special place in orchestral repertoire. Price was famously the first African American woman composer to have her work—her Symphony no. 1—performed by a major American symphony orchestra. But her career involved many more successes of which her Symphony no. 3 is a highpoint, one that gained acclaim from first lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

Taking part in the great migration, Price moved from Little Rock, Arkansas to Chicago. There, Price participated in a thriving Black musical scene, where she interacted with major musical figures such as Margarette Bonds and Nora Holt, and further developed her craft. (For more on Price’s truly astounding life and career, I recommend WPR host Stephanie Elkin’s talk “On the Life and Music of Florence Price.”)

After having fallen out from public eye, Price’s music has seen a resurgence in the 21st century, prompted in large part by the unexpected discovery of many of her unpublished compositions in 2009. In addition, recent efforts in diversity, equity, and inclusion in the classical music world have led many to Price. But to reduce Price to simply an example of an outstanding female composer of African, European, and Native American descent would overlook her unique compositional voice.

Describing her Symphony no. 3, the composer called the work “a not too deliberate attempt to picture a cross-section of present-day Negro life and thought with its heritage of that which is past, paralleled, or influenced by concepts of present day.” While the piece was clearly influenced by African American musical forms, Price developed her musical themes in a manner similar to Romantic era composers and did so with a modern twist.

At the start of the symphony, the MSO’s brass section had trouble locking in some of the opening chords, but they quickly recovered in the second phrase. Yet, at the closing of the first movement, the MSO altogether fell short of the grandeur of the climactic moment. In the second movement, on the other hand, the MSO developed wonderful textures and flowed together through the many orchestral swells.

The percussion section featured prominently in this piece, especially in the third movement, where the bass drum and cymbals generate a palpable momentum. I was most pleased by the MSO’s performance of the final movement. Unlike the first movement, the final one reached a satisfying climax befitting the end of the exciting work.

Before the concert began, Robert Reed, the executive director of the MSO, addressed the audience, thanking them for a successful season. After the previous season, Reed said that he “never takes things for granted,” and that he was delighted that the full season went on interrupted, so much so that he was doing a mental “happy dance” to celebrate the season’s conclusion.

It has been a season worth celebrating. The MSO performed varied repertoire, invited fantastic soloists to share the stage, and sounded as good as it ever has. This weekend’s concert ended the season on a high note and left me excited for next season.