The guitar always meant a lot to Machine Gun Kelly. Even as a solidly successful hip-hop star, he passed his time on the tour bus tripping on acid and watching classic Nirvana shows, noodling around on guitar.

Turning to guitar-based music may not seem like the best career move for a 30-year-old rapper, eking out a successful-enough hip-hop career to earn him a few solid acting roles. Safer to make the movies, cash the Hollywood checks, and release enough hip-hop singles to keep some street cred.

But then there’s his dad.

His dad who left him with an aunt, when he was just a teen. After his mom left, too, when he was only nine.

His dad who got him his first guitar.

An only child, Colson Baker’s parents were Christian missionaries who took him all over the world before he hit fifth grade: Egypt, Germany, Houston, Chicago.

In Denver, they split. He had no friends, but he had Jackass.

He’d watched Johnny Knoxville, Steve-O, Chris Pontius, Bam Margera and the rest of the squad doing idiotic stunts when he was in Denver. They taught him you didn’t have to be polished to be successful. You could just post a don’t-try-this-at-home warning and shoot your friends with a Taser on MTV.

Or shoot yourself with an actual gun, as Knoxville once did, in a bullet-proof vest.

“They were dressing like we were and they had cameras that looked like ours and it looked DIY,” Baker recalls. “And it had music that we liked so it was cool.”

His dad then took him to Cleveland, the Rust Belt, to be raised by an aunt.

Baker didn’t have much interest in attending Shaker Heights High School on the city’s leafy east side. His height and poverty made him a target. He was relentlessly picked on for most of high school.

“I didn’t have many friends until senior year of high school,” he says. “Those are the guys that are still with me now like Slim, Dub and my homie Little Mike.”

He would very briefly jam with friends, playing the guitar his father got him. And he listened to Cleveland-area mixtapes that he still listens to “all the time.”

He wanted to make music. In the late 2000s, Chip tha Ripper (now King Chip) and Kid Cudi were the dominant voices from Cleveland, which also had a vibrant battle-rap scene. He earned the name Machine Gun Kelly when he was 15 because he spit verses so fast. He rose fast, too.

“Back when white boys rapped/they getting they ass kicked/I was battlin’/puttin’ these rappers in caskets,” he said on his 2019 single “Hollywood Whore,” where he also rapped about going from “trailer trash to Saks Fifth.”

He actually was from the streets, in a sense: After his father (who battled depression) kicked him out of their house post-high school, MGK didn’t have a steady place to sleep, so he relied on “couch hopping,” he says. He would sling weed at the dorms at John Carroll University and work restaurant jobs.

He also learned to put on a show. He’d crowd surf, climb on anything in sight and bounce around on-and-off stage. He was a hit in his hometown, and then online.

MGK took on all-comers as a battle rapper and was an early adopter of video blogs. With a camera-ready look, a devious smile and a Tommy Lee-type body, he made KellyVision videos that gave a fun and goofy glimpse into his personality. Fans felt like they knew him.

He got his shot in 2009 at one of the most important stages in music, when he competed in Amateur Night at the Apollo. The Harlem audience is famously skeptical of white artists attempting to perform music built and nurtured by Black artists — and famously generous to those who can pull it off. He pulled off back-to-back wins.

But he wasn’t finished with Cleveland. One of the first places he got a boost from locally was the Grog Shop. Located in Cleveland Heights, the venue had become a hub for emerging artists. During a three-year stretch from 2008 through 2010, Cudi, Pittsburgh’s Wiz Khalifa and MGK all headlined on Thanksgiving night.

After seeing him perform, the Grog Shop’s Kathy Blackman saw firsthand that MGK wasn’t like his peers. On stage, he was a beast but at his core, he retained his Midwestern humbleness.

“I just remember that MGK played Thanksgiving night in 2010 to a packed house,” Blackman says. “He was always super gracious and respectful to me and the staff and down to earth, really seemed to love performing and had a great time doing it.”

A year later, he was signed by Sean Combs to Bad Boy after a strong showing at South by Southwest, and for the first time began to get the positive attention that had eluded him in his youth. His records sold well, with his first three albums (Lace Up, General Admission and Bloom) all certified gold. He played bigger and bigger theaters. He had a tour bus.

But he felt like something was missing. MGK was exploring different elements of music as far back as his days in Cleveland. After he was signed to Bad Boy, he brought his wild live show to a wider audience on the 2011 and 2012 Vans Warped Tour. Performing in front of “maybe 15-20 people” and people passing by on the Ernie Ball stage, which was a tiny side stage in the back of a truck, MGK knew he had to get theatrical to earn passerby’s attention.

“I would play [Blink-182’s] ’What’s My Age Again’ and I would just take my pants off and run around and throw water on everybody,” he says, sporting a sly grin. “You can’t walk by that and not wonder what’s going on.”

The Warped Tour shows introduced MGK to a vastly different audience than the battle rap crowds in Cleveland, but a scene he found himself down with.

“I pride myself on still being a fan,” he says. “Like when we watched Anti-Flag perform, I was in the pit, man. We went to watch our favorite bands play because those were the bands I liked and would listen to.”

Even so, he was hardly a critical favorite, and while his singles charted, only 2016’s “Bad Things,” featuring Camila Cabello, landed in the top 10.

“It was really frustrating being an anomaly because you can’t really understand those who don’t understand you,” he says, “because it would make me not understand myself.”

He was ready for a different direction, and the hints were already there for anyone who had paid close attention to his music. On “Hollywood Whore,” he had collaborated with producer Ramii, who described the track as “our interpretation of a Linkin Park song.” A track with Trippie Red, “Candy,” had an emo tinge. And he was hanging out with rock musicians, like Blink-182 vet Travis Barker, who he’d known for nearly a decade.

Machine Gun Kelly was playing guitar again. He had reconciled with his dad, and the guitar was one of the things they bonded over. “He got me my first guitar and I didn’t understand the power of that when I was a kid.”

When his father died in July, he coped in the only way he knew possible: his music.

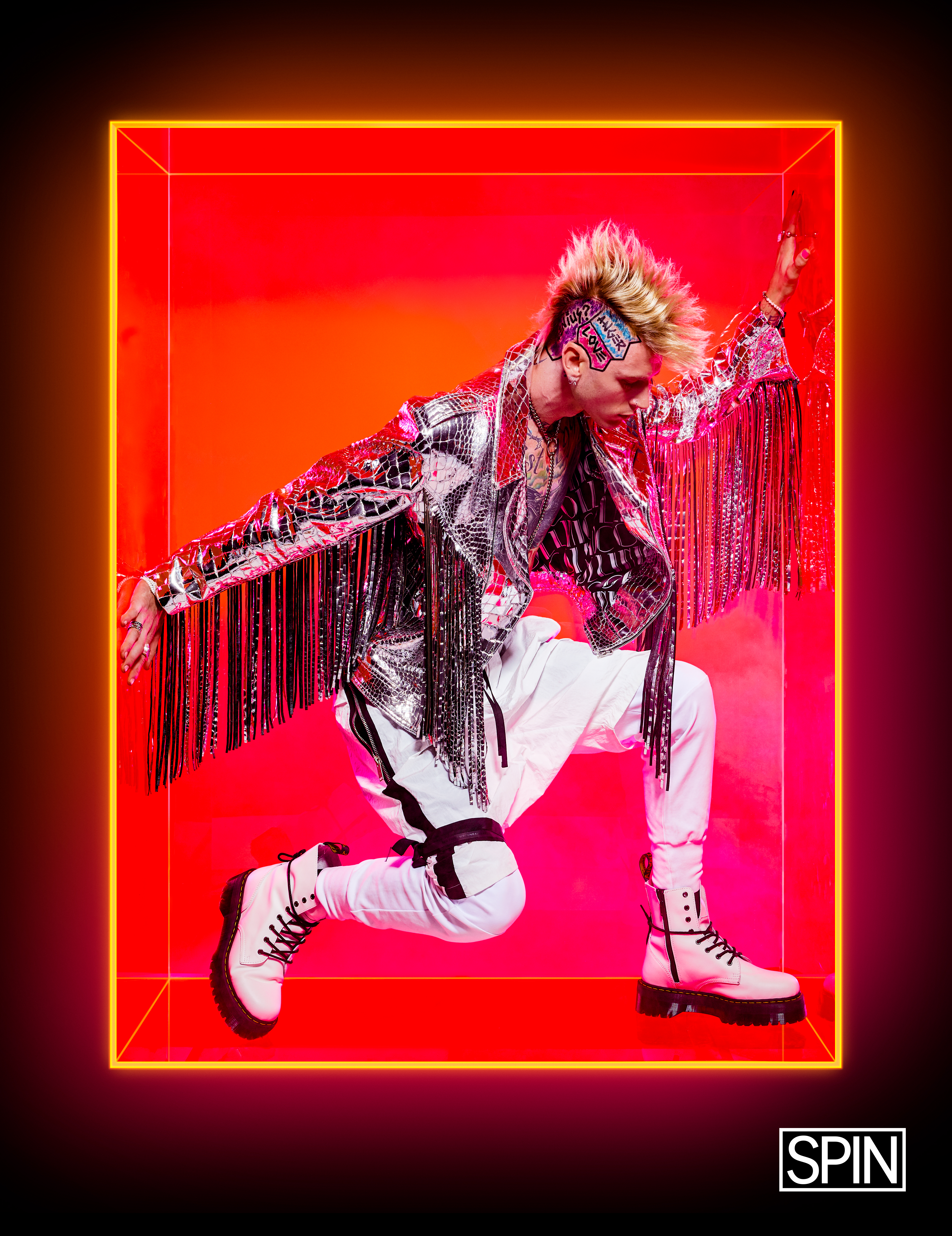

Taking a break from a photo and video shoot in downtown Los Angeles after just returning from a film shoot in Montana, Kelly, who is sporting an unbuttoned black-and-blue flannel get-up that exposes the wall of tattoos on his torso (including the phrase Tickets to My Downfall under his neck), leans back on a loveseat, takes a breath and looks down at the ground. He’s a bit weary, but not weary enough to resist taking a hit from a beautifully-rolled blunt. Thinking for a second, he remembers the moment that would plot out — at least he thought so at the time — the trajectory of his 2020.

“That meeting did exactly what I wanted it to do,” MGK says, “which was to have everybody, as soon as I left the room, say to each other ‘What the fuck is Machine Gun Kelly doing?’’’

The meeting he’s referring to took place at Interscope Records in January. He had already started working on a pop-punk album with Barker and had his first song ready to go. MGK was excited to show it off for his label, maybe a little too excited.

Kelly was captured on video by Barker jumping and thrusting himself recklessly on a conference table in a meeting at Interscope Records as execs listened to his latest song. Instead of winning over doubters, MGK’s enthusiasm was widely mocked online, becoming a meme and punchline in the process. He knew he was being laughed at, but it only strengthened his resolve.

“How shitty would it have been if I went in there and they were like, ‘It’s cool.’ I mean, a lot of things are cool. My breakfast was cool. I don’t want ‘cool’ I want unforgettable,” he says.

“He always had a clear vision for what he wanted to do,” producer Ramii, a longtime collaborator says. “He knew where he was going. He stood out because he made music people could feel and relate to.”

Tapping Barker to produce and armed with a pink guitar, MGK got to work on an album that would become Tickets to My Downfall. Coming into the studio “inebriated” forced him to come up with “unfiltered lyrics” that reflected how he felt at that moment. The spontaneity of the sessions allowed MGK to thrive and the sessions created organic moments — like the inclusion of Halsey on “Forget Me Too.”

“She was driving by the studio,” he remembers. “Unknowingly, I called her and she was in the area, and she came by and did the track.”

The free-flowing nature sessions helped him channel his emotions during his difficult times — like coming up with “Lonely.” The song was originally going to be about the aunt who raised him, but when his father died, it evolved into a tribute to both of them. Outside of his 11-year-old daughter, the two were his closest remaining blood relatives. Now he had neither.

“I called Travis after my father had passed and I already had that concept of a song for my aunt who was my closest family member, who passed too. Ironically, me and my father both lived with my aunt. That song is like the house, you know, they both were in the house, and they both are in that song. It was either take it [sharing his emotions of grief] in that song or I would have found some other way, which would have been much less friendly to myself to get my anger and pain and grief out. So I was grateful that Travis allowed me to come in and have that cathartic moment in the booth.”

The song, the album and even begrudging critical acceptance showed that MGK made the right decision by taking an enormous chance. Tickets to My Downfall was released in September. It was Kelly’s first No. 1 album.

But why pop-punk and why now?

“It needed a face again. It needed someone to walk up in the camera and go ‘fuck you.’”

Something he’s quite comfortable with doing.

Even though he’s mostly not raising hell and only startling record execs these days, MGK’s wild man image opened up other opportunities outside of music. His lanky 6’4” frame, Billy Idol-esque hair and a striking presence, once mocked, allowed him to break into something he’d been doing since his vlogs: acting.

After roles in 2014’s Beyond the Lights, Cameron Crowe’s short-lived Showtime series Roadies and the Netflix film Birdbox, MGK showed he could be as charismatic on the screen as on the mic. Then he got the audition of his career: to play Tommy Lee in the 2019 Motley Crue biopic The Dirt. And who directed the movie? Jackass co-creator Jeff Tremaine.

Auditioning for the role six times, when MGK finally got the part he reached out to Lee, who he’d known for a few years.

“One day I just got a call from fucking Colson and he’s like, ‘Dude, you’re not gonna believe this, I’m playing you in the movie.’ I had no idea,” Lee says. “There’s so many similarities [between us], that it’s almost frightening. Same build, same walk.”

What stood out to Lee was MGK’s dedication to the role. After landing the part, MGK went over to Lee’s house and went over the script with him line-by-line in order to capture the legendary drummer’s ethos.

“He took drum lessons for four months to capture mannerisms or fucking whatever you call my style — like to twirl on the sticks and bouncing sticks off the snare drum and shooting them up into the air and catching them and, you know, cymbal grabs and all these things that I do,” he says. “I was so blown away, man. I don’t think I’ve ever seen that much dedication to anything, actually. Whether it’s a movie or making a record.”

His film career blossomed. Roles were coming in quickly. He featured in fellow The Dirt star Pete Davidson’s The King of Staten Island and earlier this year right before COVID struck, filmed Midnight in the Switchgrass. There, he first met Megan Fox and a romance kindled. The duo quickly became a top subject for the tabloids, which hasn’t changed how Fox has positively influenced MGK’s life.

When they met, he was still working on Tickets for My Downfall. An album that is full of angst, sadness that captured an artist at a pivotal career point, also served as a personal diary of riding out the good and bad of 2020.

As much as “Lonely” was raw, “Banyan Tree” showed MGK vulnerable in a romantic fashion. The interlude is a sweet conversation between the two where he says how much he cherishes the times the two have together. He hasn’t been shy to showcase their relationship on his social media and how important she’s been to his happiness.

“We as musicians, just like showing off things in material form,” MGK says of “Banyan Tree.” “But on this, I wanted to kind of show the extravagance of attaining something in emotional form as well. I really don’t think people have given my layers much of a look. I think they see something on the surface and stop there. So, I mean, if anything, I hope this encourages people to look beyond the obvious.”

Fox also starred in MGK’s video for “Bloody Valentine,” which was a somewhat surprise winner of the MTV VMAs’ Best Alternative Video category, which had been dormant for 22 years — the previous winner was Green Day’s “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life).”

“That brought back dreaming to me,” he says, then pauses. He continues: “I made Tickets to My Downfall on my own accord, for only for the love of music. At that time, I was completely written off. My agents weren’t getting blown up, it wasn’t like an exponential time for my career. I approached the album already kind of as a failure, which is what gave it such a genuine angst.”

When Tickets to My Downfall was released in September, it debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 — the first rock album to do so in 2020.

For someone who once bounced from couch-to-couch, taking home that Moonman, a month before Tickets’ release no less, was a sign that the universe was finally giving back to a guy searching for meaning.

“If I had to stomach getting laughed at for the six months that that video was out without anyone having context of what was coming out of that video in exchange for a lifetime of that music being loved and enjoyed by people that is totally worth it.”

MGK is already back in the studio. He and Barker have already banged out new songs — though he’s not specific to what happens next.

“I’m not sure where they belong, but that’s always a good thing,” he admits.

While Tickets to My Downfall was his personal journey, the upcoming stage film of the album, Downfalls High, aims to take his experience and generalize it.

“It’s a story about finding and expressing freedom and pain and being lost and being found being lost again.”

Which is also the story of Machine Gun Kelly.

Following the shoot for this piece, MGK is tapped on his shoulder by first his manager, then his publicist. He takes a deep breath and looks over cautiously. It’s been a long day — especially when you factor in the copious amounts of tequila poured by Fox and his steady stream of blunts. But this is different: his label boss, Interscope CEO John Janick, has some news and wants to talk to him now. Shaking off whatever buzz he has, MGK calmly grabs his publicist’s phone and calls Janick and it’s worth it: MGK has been added to the lineup of the AMAs.

He pumps his fist in the air exuberantly.

After pacing around the room for a second, MGK sits on the floor and cracks a big smile before taking another hit from another blunt. Now, he’s sprawled out on the cold cement studio floor and gazes at the ceiling as a red sweatsuit-wearing Fox perched on a couch behind him beams with pride. She immediately hops on her phone, smiling and quiet. MGK looks back at Fox, smiles, takes a breath and glances back at me.

“This isn’t supposed to happen on your fifth album,” he says directly and quietly.

He’s right. But it did.

![Conor McGregor Calls Machine Gun Kelly A “Vanilla Boy Rapper” After VMA Drama [Video]](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/conor-mcgregor-calls-machine-gun-kelly-a-vanilla-boy-rapper-after-vma-drama-video-327x219.jpg)