LVMH pioneered the concept of a luxury group in the 1980s and is largely credited with having saved the French fashion and leather goods industry from oblivion. For years, it looked like LVMH might be the sole consolidator in fashion and leather goods, with Swatch and Richemont carving out dominant positions in hard luxury (saving the Swiss mechanical watch industry from destitution). The entry of PPR (now Kering) into the game with the 1999 acquisitions of Gucci and Sanofi Beauté (which owned YSL and YSL Beauty) changed the game, validating LVMH’s strategy and opening the door for other, albeit smaller, consolidators such as Capri Holdings, Tapestry and Prada Group. What’s driving this race to the top? Who has benefitted? And who has lost out?

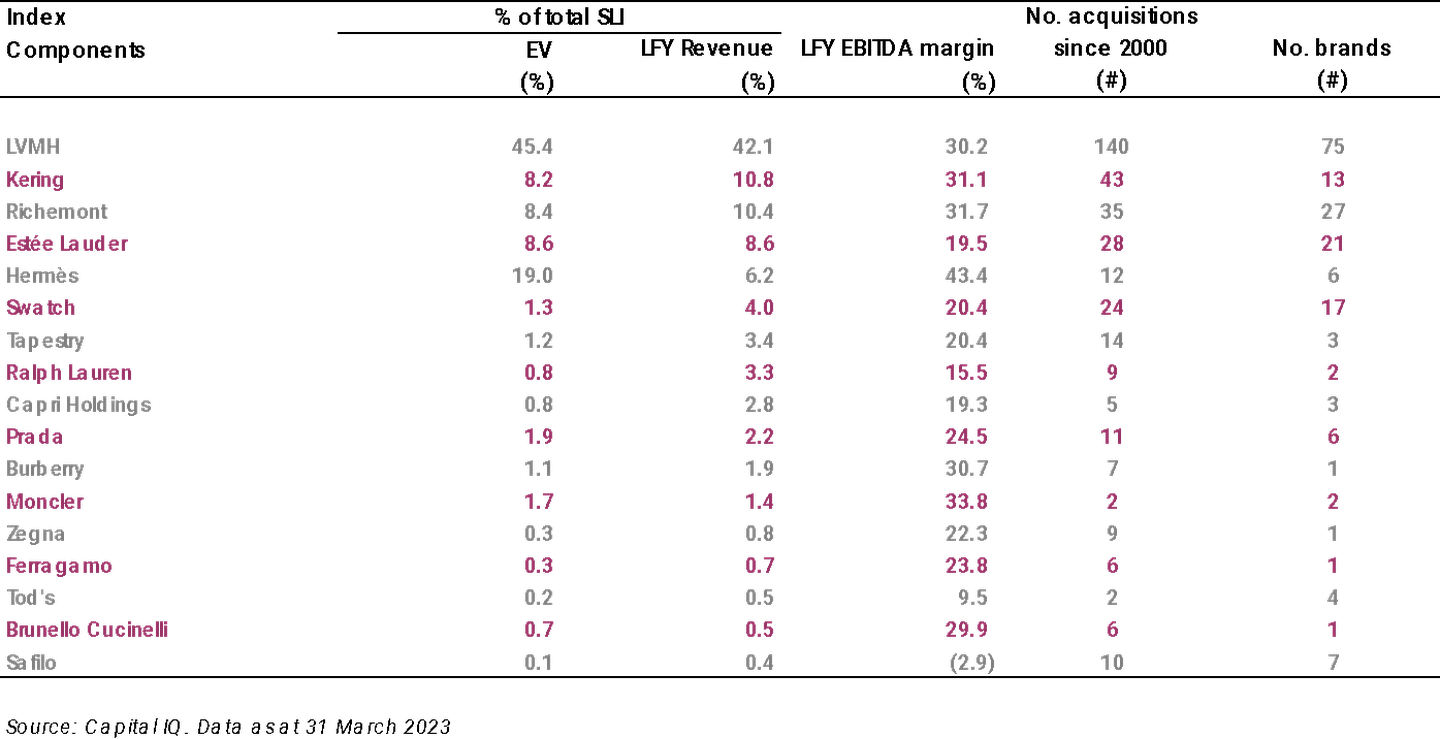

The top 5 companies in the Savigny Luxury Index account for close to 80 percent of the total sales generated by the 17 companies which populate the SLI and they own 142 out of the 190 brands covered by the index. LVMH is in a league of its own, accounting for 42 percent of SLI revenue, 45 percent of SLI enterprise value, and 75 of the 190 brands within the index. LVMH has also made by far the most acquisitions of SLI players, making 140 deals since 2000, more than triple that of its closest competitor, Kering.

Profitability is a key driver behind the race for scale in luxury. The top five companies in the SLI, which all have a turnover in excess of €10 billion, had an average EBITDA margin of 31.2 percent last year. That compares with an average EBITDA margin of 20.6 percent for the rest of the SLI. Some of the smaller companies score well in terms of profitability but this is most likely driven by the fact that they have a strong hero product, such as the trench coat for Burberry, or are specialised in a particular segment such as winter jackets for Moncler or cashmere/high end apparel for Brunello Cucinelli.

The correlation between size and profitability stems from the virtuous cycle of lower unit production costs (as the size of production runs increase), the power of heft when negotiating terms with retailers, landlords and advertising outlets and, as long as the brand does not become too ubiquitous, increased pricing power.

On this last point, Hermès is a master class, with waiting lists for its Birkin bags having stretched up to six years in the past, allowing the brand to charge a significant premium for its so-called “quota” bags (the Kelly, Birkin and Constance). The legendary leather goods company posted yet another record EBITDA margin of over 40 percent last year.

Kering and LVMH have also demonstrated the benefits of multiple brand ownership, whether it is LVMH leveraging on the power of Christian Dior to negotiate better placement in beauty stores for Guerlain or Givenchy or Kering shifting management resources from brand to brand where needed, such as Marco Bizzarri, previously CEO of Bottega Venetta and head of Kering’s luxury couture and leather goods unit, being appointed CEO of Gucci in 2015.

There is also an element of diversification of risk that comes into play, combined with the ability to push a hotter/fresher brand when brand fatigue emerges at a stablemate, although the reality is that the two groups are still reliant on their flagship brands, Louis Vuitton and Gucci, for the bulk of their profits (particularly so in the case of Kering and Gucci).

LVMH’s ambitions in the watches and jewellery sector date back to the late 1990′s when the group started by buying Zenith, Ebel, Chaumet and Tag Heuer and setting up a jewellery joint venture with De Beers. The group also engaged in a fierce duel with Richemont to acquire Jaeger-LeCoultre, IWC and Lange & Soehne but ending up losing due to Richemont’s strategic imperative to deliver what was then a landmark deal, leading the Swiss-based group to pay well over the odds at the time.

LVMH was also thought to have paid too much when it acquired Bulgari in 2011 at a premium of almost 60 percent on the Italian jeweller’s share price, valuing the company at €3.7 billion. Or did they? With hindsight, perhaps not. And that is the point. These groups had the scale, the vision, the management and financial resources to vastly improve the trajectory of the brands they acquired. This has played out again more recently with LVMH’s acquisition of Tiffany for $15.8 billion, a deal which propelled the group’s watches and jewellery division to the number two position in the industry, with €10.5 billion in sales (behind only Richemont with €14.5 billion sales).

While LVMH seemed to have a case of pandemic-induced buyer’s remorse before closing the Tiffany deal, managing to renegotiate a slightly lower price, that feels like a distant memory now with the brand performing extremely well, fuelled by impactful campaigns featuring Beyonce and Jay Z, the successful launch of its Lock jewellery collection, solid growth in its high jewellery business and, now, the relaunch of its legendary Fifth Avenue store.

No doubt this relatively rapid closing of the gap with Richemont has fuelled the speculation that Richemont and Kering could merge and thus give LVMH a run for its money. Worth pointing out is the fact that a combined Richemont/Kering would still only be half the size of LVMH in terms of turnover and that the merger would do nothing to change the relative market positions of the groups in fashion/leather goods or in watches/jewellery.

A killer blow would be for either LVMH to acquire Richemont to become the number one luxury watches/jewellery group in the world (it is already the number one luxury fashion and leather goods group by a mile) or to acquire Estée Lauder in order to become the number one luxury beauty group in the world. Anything less, except for perhaps a bid for Chanel, would do little to change the broad dynamics that already exist in the luxury stratosphere.

Tapestry embarked on a multi-brand strategy in 2015 with the acquisition of Stuart Weitzman followed by the 2017 acquisition of Kate Spade, but the group made no moves since, focussing on cleaning up its distribution. (Two of the group’s former CEO’s joined forces to set up a SPAC in 2021, which currently has a market value of $350 million, which does not give them much firepower considering that the latest luxury SPAC to provide a home for a brand was Zegna, which listed at a valuation of $2.4 billion).

Capri threw its hat in the ring in 2017 with the acquisition of Jimmy Choo followed by the 2018 acquisition of Versace. The lack of strategic overlap between its core Michael Kors brand and Jimmy Choo and Versace, the lack of scale of all three brands and the persistently low relative stock market valuation of the group and its relatively high leverage means Capri’s ambitions to build a luxury conglomerate seems to have been put on hold.

In Italy, both Prada and Moncler have been touted as consolidators. Prada successfully launched sister brand Miu Miu and has acquired two shoe brands (Church’s and Car Shoe) as well as a café (Marchesi). But the group’s ambitions to scale were somewhat thwarted by the unlucky timing of its IPO, which saddled Prada with a lot of debt.

Whether it’s Tapestry and Coach in the US or Prada and Moncler in Italy, the issue with the next tier of players is that there is such a significant gap between these contenders, which individually account for between 2 and 3 percent of the SLI’s revenue and between 1 and 2 percent of the SLI’s enterprise value, and the SLI’s top five companies. This means that they are more likely to be acquisition opportunities for the likes of LVMH and Kering than consolidators themselves.

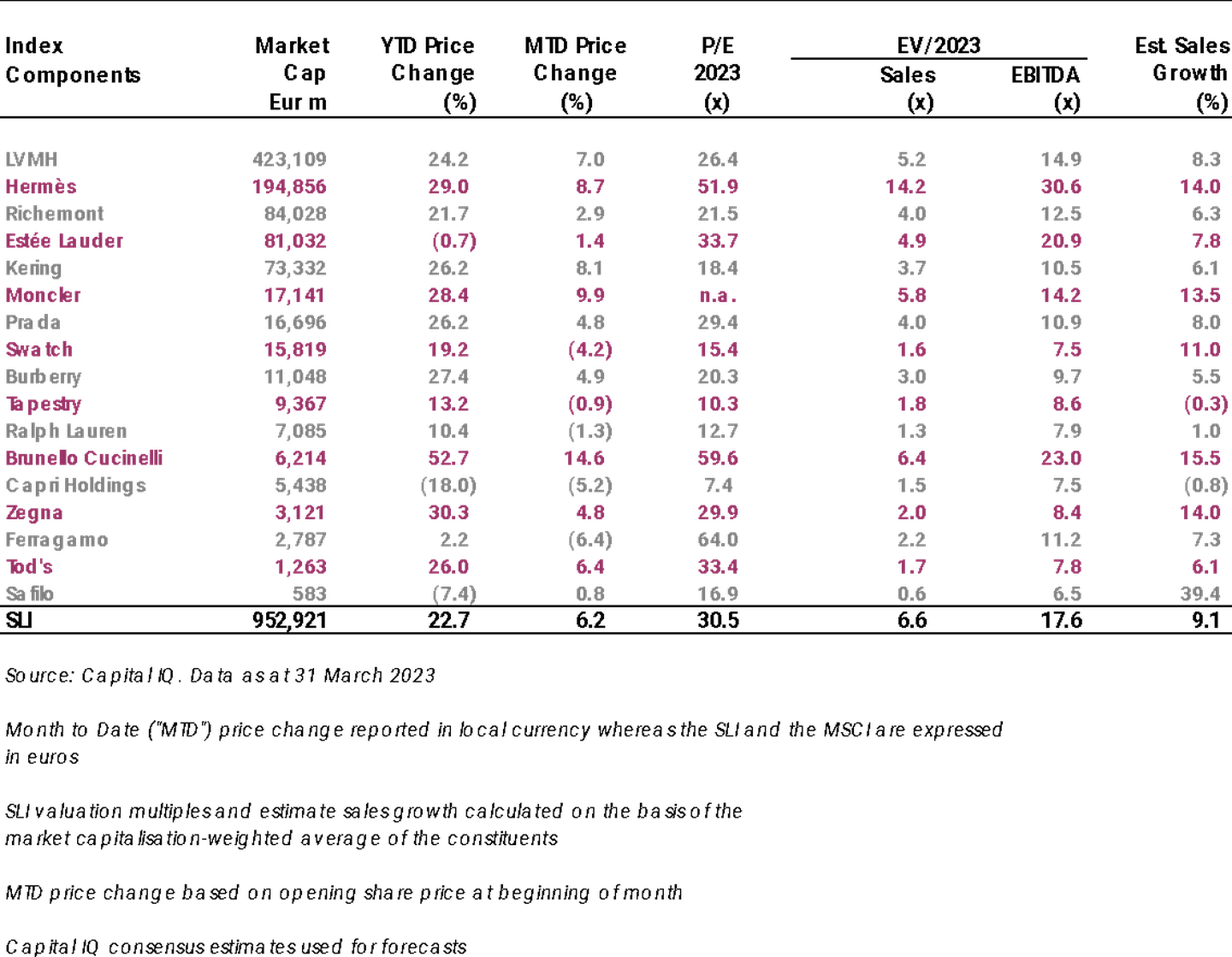

The Savigny Luxury Index (“SLI”) gained almost 6 percent in March, driven by improved sentiment around the first quarter performance of the sector. Conversely the MSCI declined by almost 5 percentage points due to continued prospects of further interest rate hikes worldwide.

SLI vs. MSCI

Going up

- Brunello Cucinelli published its 2022 annual report showing revenue growth of 29.1 percent and EBIT growth of 74.5 percent. The luxury apparel and cashmere group’s shares ended the month 14.6 percent up.

- Moncler’s 2022 revenue and EBIT came in ahead of expectations, with strong performance in China despite continuing lockdowns. The company is optimistic about 2023. Moncler’s share price rose by 9.9 percent in March.

- Hermès’ share price rose 8.7 percent in March in anticipation of strong first quarter revenue growth (on which it over-delivered), despite tougher comps than the rest of the sector given that Hermès’ performance was not as badly affected by lockdowns in China in the first quarter of 2022, and thanks to the perceived strength of the brand’s pricing power vs its peers.

Going down

- Ferragamo’s share price fell 6.4 percent in March on the back of 2022′s annual results showing progression in revenue but a further decline in operating margin to 10.2 percent (the group’s EBITDA margin for 2022 was 23.8 percent, down from 26.8 percent in 2021). Analysts estimate a further decline in margins for 2023 as Ferragamo continues its lengthy turnaround.

- Capri Holdings lost 5.2 percent in March. The struggling US group’s shares dropped 28.2 percent on 8 February on the back of disappointing third quarter results in which declines in sales and profits were reported partly due to price increases at Michael Kors dampening demand.

What to watch

As the top groups consolidate their power, do small deals and small brands have no hope? Not necessarily. While scale offers an overwhelming advantage and big brands have gained market share through the pandemic, the overall luxury market is growing — just as the world is growing. That means there’s still space for new entrants.

This is particularly true in beauty, where wholesaling to multi-brand retailers remains the norm, allowing for faster growth in a sector where creativity and image can trump craftsmanship and heritage (see: Byredo, Drunk Elephant and Aesop).

And yet, while heritage can be overcome by creativity, it is effectively a barrier to entry given the length of time it takes to develop. The good news is that it can be acquired and successfully relaunched, for example at Moynat (LVMH), Schiaparelli (Tod’s) or Paul Poiret, which is now being revived as a premium beauty brand by Korean retailer Shinsegae. Last but not least there’s Gerald Genta, the namesake brand of the legendary Swiss watch designer behind Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak and Patek Philippe’s Nautilus, which was acquired by LVMH as part of the Bulgari deal in 2011 and has been relaunched this year.

Sector valuation

Pierre Mallevays is a partner and co-head of merchant banking at Stanhope Capital Group.