Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Fashion myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The trend towards the casualisation of fancy clothes is very old. The American economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen noted at the turn of the 20th century that, at the same time the clothing of the leisure classes must display wealth and taste, the wearer must never be seen to be working at this display, or else risk undermining its impact. The message must always be ease. This tension has worked itself out, by fits and starts, over the decades since.

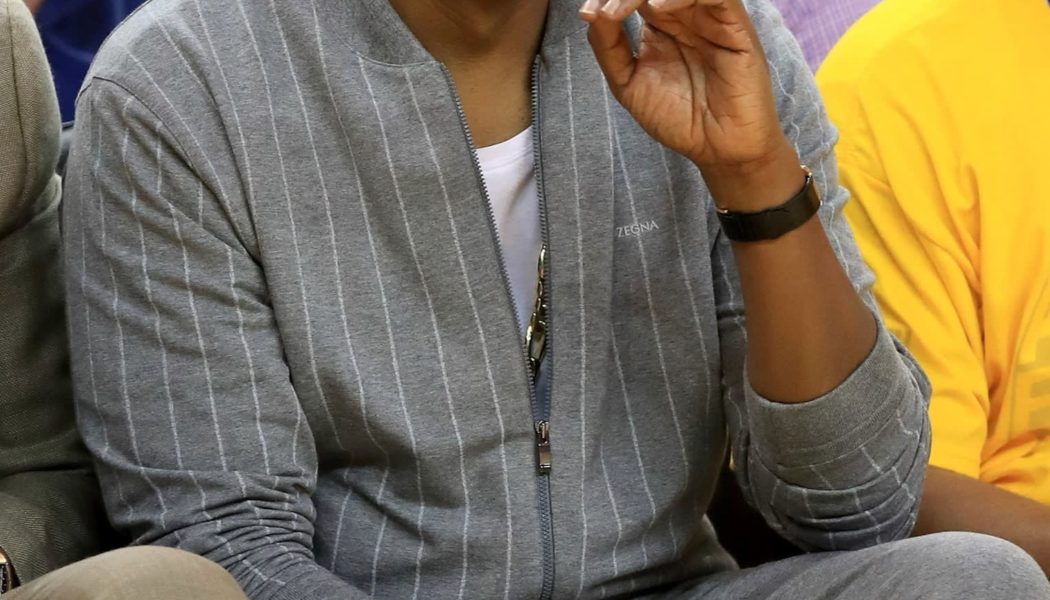

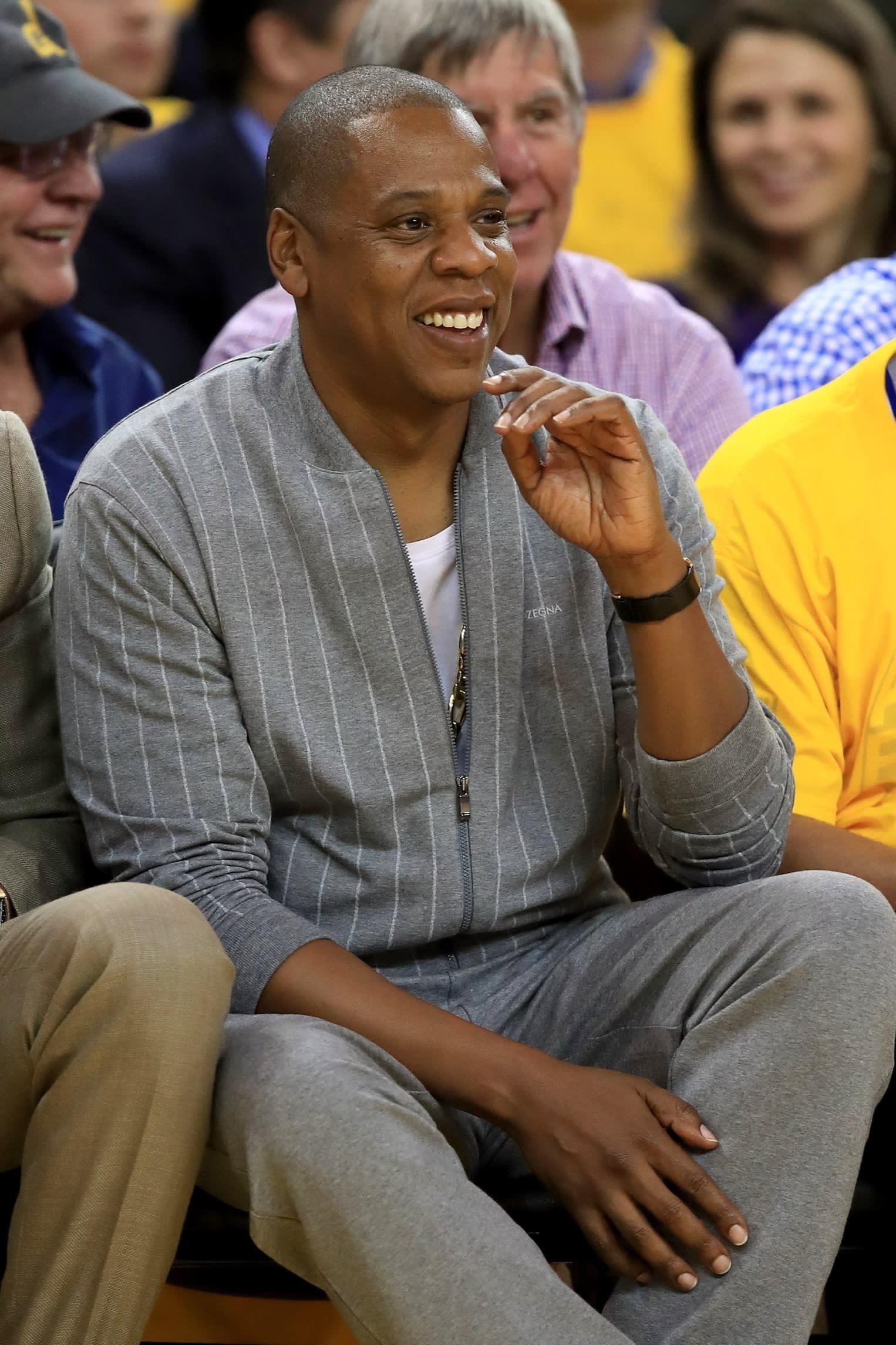

But casualisation may now be reaching an apotheosis, or possibly just a dead end. Increasingly, luxury clothes are all but indistinguishable from the casual clothes they imitate — sportswear and workwear, mostly. Luxury items still serve their core purpose of separating the rich from the poor, the upper from the lower, and the discerning from the vulgar. But to achieve this, they increasingly have to depend on price alone.

Witness, for example, the leisure sneaker phenomenon: you can buy a $1,000-ish pair from Loro Piana, or Louis Vuitton, or The Row, or Brunello Cucinelli, or Zegna. Beside their prices, what they all have in common is that they are not better looking, more refined, more comfortable or sturdier than a nice pair of Nike’s that will set you back less than $100 (manufacturing technology has driven the real cost of good sneakers down dramatically in recent years). The luxury sneakers do, however, successfully signal to a select group of people that you are rich.

The problem is that to a different select group of people, they signal that you are an idiot. The imperative to go casual has been taken as far as it can go, to the point where it makes a laughable contrast with the imperative to differentiate with price.

It is not just the sneakers. You have a wide field of choice among $500 cotton T-shirts, $1,000 sweatshirts, and so on. The industry’s best effort to justify these prices is to make athleisure — puffer coats, joggers, whatever — out of cashmere and vicuña. And maybe vicuña keeps its shape a little longer, looks a little nicer, or is softer to the touch. But this is not the point. The expensive materials are there to resolve a contradiction that is becoming a bit too obvious for intelligent people, however vain, to bear.

I’m not asserting that all very expensive clothes are laughable. Things that are handmade or handfinished entail a lot of expensive skilled labour. A bespoke suit or dress at $5,000 has much more economic logic to it than a $500 T-shirt. Whether bespoke is worth the price is another question (a question that I, living on a journalist’s salary, will never be able to answer). In general, good construction costs a lot. At the same time, good design is beautiful, and good designers deserve to be paid a premium for their work. But the prices of luxury goods have, quite obviously, shot beyond what the brands’ chatter about look and quality can justify.

I am not saying that we should just simply stop worrying about status and its display. One might as well argue that we should give up on walking on two legs and revert to scampering on all fours. Status seeking is wired into us in the same way language is. Those who insist (as several will in the comments section below) that they care nothing for status and its symbols invariably suffer the most from class anxiety, and are left the most indignant by the little slights and power plays that make up everyday life. I’d go further: clothes and other matters of taste are a relatively benign way to signal and celebrate status, much to be preferred to snobbery based on, say, political party or ancestry.

What I am saying is that, as a move in the status game, casualisation may be played only so many times over so many years; like Marx’s capitalism, its contradictions must become fatal eventually. Eventually, one becomes what one is imitating — a person who is dressed indifferently — and the show loses its point, if not its price tag.

What would it mean if that were so? It would mean that goofy pretensions of “elevated athleisure” and “quiet luxury” are, as business models, living on borrowed time. It would also mean that sending social messages through casual clothes will become harder and riskier, because one could no longer depend on just paying up for certain brands to do the work. And it may be that we just have to find a new medium for showing off.

The more likely outcome is that anyone who was ever willing to pay $1,000 for a pair of sneakers will just keep on paying. If they had the imagination to spend their money elsewhere, they would have done so already. Judgements of taste are subtle and changeable and evolve with history. Vanity, on the other hand, is muscular and stupid, and smashes its way ahead.

Robert Armstrong is the FT’s US financial commentator

Follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen