Cassidy STEPHENS

Jul 7, 2023

Cassidy STEPHENS

Jul 7, 2023

The luxury goods industry is increasingly a question of scale. Particularly when it comes to retail. While the number of shops around the world has remained fairly stable since the pandemic, the shape and size of shops have changed dramatically. On the one hand, there is the rise of the industry giants, who maintain a stronghold on the best locations and huge spaces, and on the other, smaller or medium-sized players who have to make do with what’s left. This is the conclusion drawn by Bernstein in the ‘Luxury Retail Evolution’ study carried out for the Italian association of luxury companies Altagamma.

“In the four years since the Covid-19 crisis, the network of luxury shops around the world has changed very little, increasing by just 0.5%, especially in Asia-Pacific, Europe and the Middle East. If we exclude Michael Kors, which closed 132 shops over the period, mainly in the United States, the North American market has also proved attractive, with new destinations such as Saint-Louis, Detroit and Austin, previously shunned by the houses,” summarises Luca Solca, author of the report and senior luxury analyst at the firm.

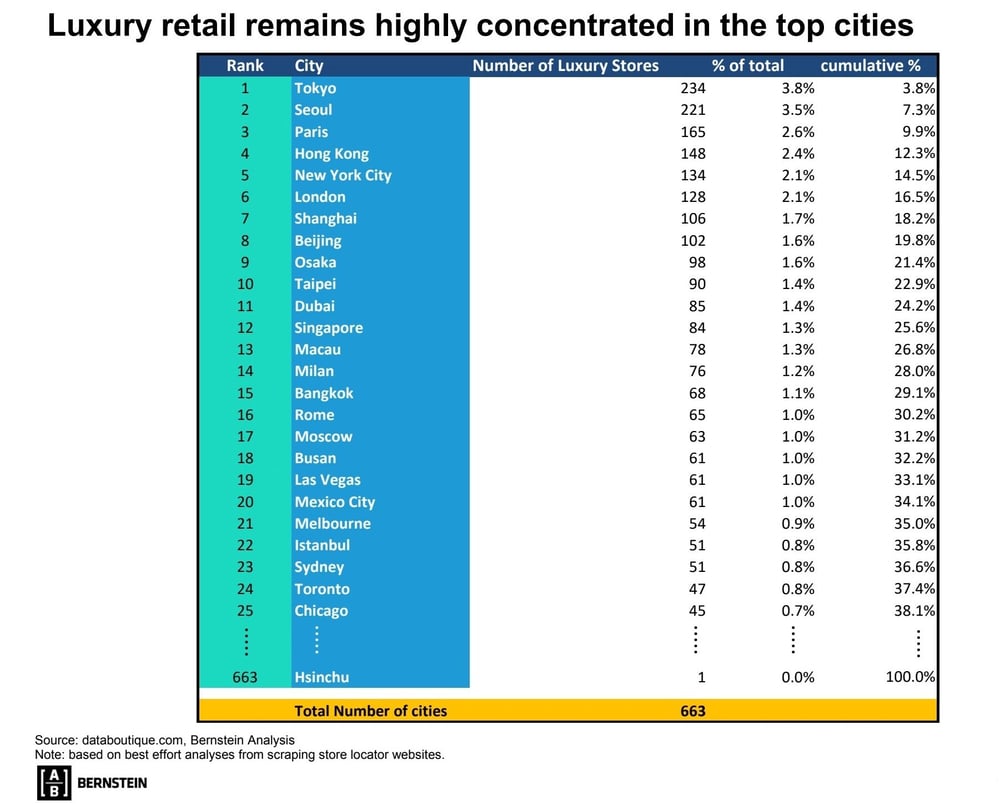

Luxury retail is concentrated in just 25 cities, with Tokyo, Seoul, Paris, Hong Kong, New York, London, Shanghai, Beijing, Osaka and Taipei topping the list. “Major investments have been concentrated in the French capital,” the analyst points out, highlighting the example of Christian Dior‘s flagship store at 30 avenue Montaigne in Paris, which was completely renovated and extended in 2022. The historic address, now spread over more than 10,000 square metres, has been expanded beyond its purely commercial space to include a café, a restaurant, three gardens, a museum housing, among other things, the models’ dressing room and the founder’s office, as well as a suite reserved for the most affluent customers who want to treat themselves to a night on the premises.

“It’s no longer just a question of using the most precious materials, such as marble and others, to impress visitors, but transforming the shop into a unique and meaningful place, linked to the brand’s roots. The idea is to make this space memorable and non-replicable, with distinctive and Instagrammable elements, to make it a destination in its own right in the same way as other must-see Parisian tourist sites,” explains Luca Solca.

“Dior’s flagship on avenue Montaigne is a multi-layered shop, designed to welcome everyone and retain consumers as long as possible. It caters just as much for the visitor who will spend a few euros on a coffee as for those who will treat themselves to the suite or exceptional items for much more,” he continues, describing these new types of shop as “cash machines”.

These new-generation points of sale require substantial investment, but on the scale of the major groups, these costs do not weigh very heavily, and these “megastores” are proving to be highly profitable, with sales of hundreds of millions of euros and high margins. The study, which was presented at a conference in Milan, concludes that these stores have gone beyond their role as retail spaces and image-boosters, becoming real attractions.

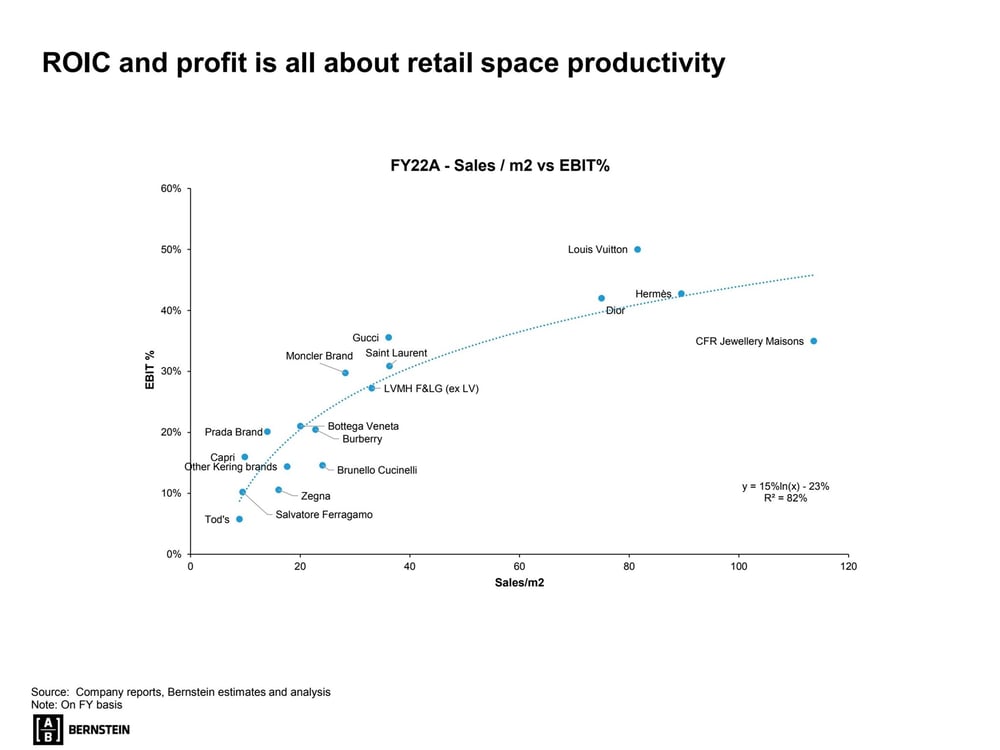

This role has increased tenfold with the multiplication of parallel initiatives, which have developed exponentially in recent years within shops. These include collaborations, pop-ups, events, artistic interventions in-store or on the facades, catering, travelling exhibitions, VIP lounges, fashion shows and more. They have enabled the luxury goods industry to increase its sales per square metre, “a key indicator that should guide luxury companies, enabling them to bear fixed costs (rents and salaries) and investments, while making a profit,” emphasises Luca Solca.

“These initiatives, which translated into competitive advantages, were gradually copied by everyone, but their accumulation and continuous increase on the part of the major houses ended up creating an insurmountable barrier for smaller brands. This is all the more true given that by directly managing a large part of their network, which allows them to control prices and the environment, the big names have ensured themselves a lead, which has only increased in recent years,” notes the analyst, for whom “the scale factor has become a fundamental asset.”

“An average company with sales of a few hundred million euros, or even 1 or 2 billion euros, will never be able to compete with a company that injects 500 million euros into a single boutique, as LVMH did for the Tiffany flagship in New York,” he says.

But the race for gigantism continues, as illustrated by the layout of brands in China’s major new shopping centres, such as Plaza 66 or the IFC Mall in Shanghai. “Two or four years ago, if a brand had two floors, it was considered a great success. Today, you need to have at least four floors,” says the Bernstein analyst. As a result, due to a lack of space or good locations, several labels have had to leave these large complexes, like Zegna, a pioneer in China.

“Under these conditions, we can’t play on the same field. It’s clear that Louis Vuitton, Dior, Chanel and Hermès are in a league of their own,” commented Etro CEO Fabrizio Cardinali, who attended the Altagamma conference. “We are faced with a luxury market that is increasingly oligopolistic,” he concludes.

With fewer resources, medium-sized luxury companies can nevertheless act on other levers, such as creativity, without trying to copy the big brands, which often proves counter-productive. “You need pragmatism to find less expensive locations and a certain amount of humility and realism to use originality and inventiveness to differentiate yourself,” says Luca Solca.

Copyright © 2023 FashionNetwork.com All rights reserved.