Bottles of Chanel perfume on display at Saks Fifth Avenue.

Photo: Sarah Blesener/Bloomberg News

Hermès sells $50 packs of cardboard nail files and $105 hand cream. Luxury brands shift millions of these kinds of small treats each year to shoppers who may not be able to afford a $10,000 handbag.

It is this more affordable part of the luxury goods industry that is now shaping up to be a weak spot.

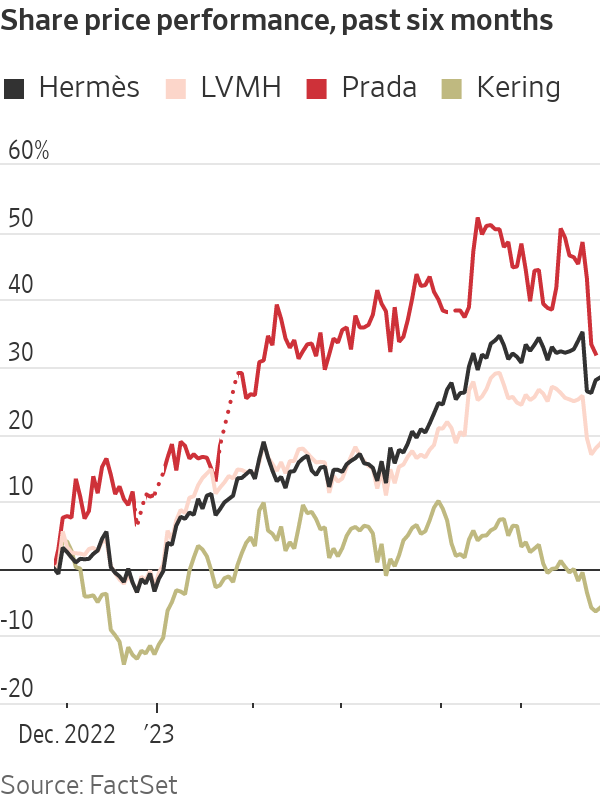

European luxury stocks lost billions of euros in value this week. Prada fell 11%, while Hermès and LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, which are considered the two safest bets in the industry, dipped 5%. Investors seem to have been spooked by comments at an industry conference that demand for entry-priced designer goods like sneakers or wallets that target so-called aspirational shoppers is falling in the U.S.

The trend isn’t new, but it is gaining steam. Credit-card data shows U.S. luxury spending has been cooling for at least five months, especially among younger shoppers who have been squeezed by inflation. In April, Americans spent 18% less than they did in the same month of last year, according to Citi luxury analyst Thomas Chauvet, whose data tracks U.S. spending both at home and overseas. On Wednesday, Chanel, which is privately owned but reports annual sales, became the latest brand to say it has noticed a change in its American stores.

Expensive brands have a reputation for selling to the superrich, but they rely heavily on shoppers further down the income scale too. Luxury sales are driven by “millions of people buying small things and a handful of people spending gigantic amounts of money,” according to Luca Solca, luxury goods analyst at Bernstein.

The top 5% of wealthiest shoppers drive around 40% of global luxury sales, according to a report from Boston Consulting Group. The rest comes from affluent consumers who spend up to €2,000 a year on luxury goods, equivalent to $2,147 at current exchange rates.

The top end of the market is growing much faster—by 2025, the richest shoppers will be responsible for 60% of luxury sales, based on BCG’s forecasts. But the industry still needs aspirational spenders for a big chunk of business.

If these shoppers are tightening their belts, luxury stocks may not be as defensive as investors hoped. And as trends in Europe tend to lag the U.S. market by a few months, a slowdown may be on the way in that market too.

Companies like Burberry that have younger and more price-sensitive customers would be hit harder by a slowdown than higher-end competitors. Hermès made 11% of group sales from entry-level products like cosmetics, perfumes and silk scarves in the first quarter of 2023—a significant chunk of its business but probably lower than the industry average.

LVMH made almost one-third of its overall sales from divisions that sell goods like lipsticks, blushers and perfumes. These businesses are still performing very well, but the Paris-based company warned on its first-quarter results call that its Hennessy cognac brand is under pressure in the U.S., as inflation has forced some drinkers to cut back.

Even after this week’s falls, European luxury shares have gained around 16% on average since January, ahead of the 11% increase in the MSCI Europe Index. At the same time, some luxury shoppers have been forced to trim their spending.

Investors may soon find out how reliant some ritzy brands are on small-ticket buyers.

Write to Carol Ryan at carol.ryan@wsj.com