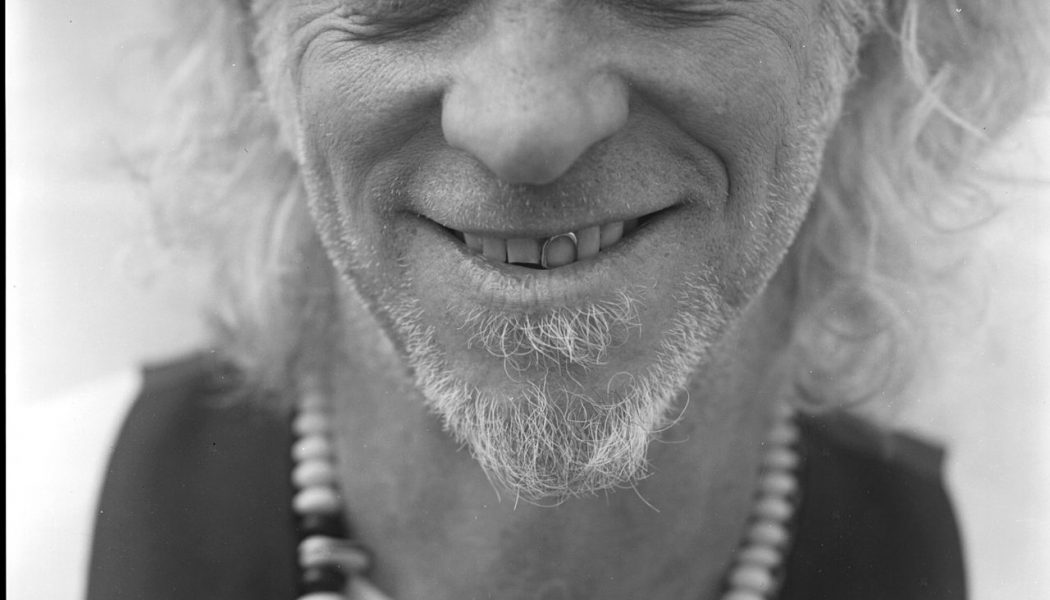

Only Mississippian Jimbo Mathus and Chicagoan Andrew Bird could compose an album so different from their platinum-selling Squirrel Nut Zippers’ roots, yet with the same sense of tender nostalgia that will endure until the end of time.

Co-written and performed exclusively by the two of them, their new record, These 13, is undoubtedly American folk, an homage to tradition, songwriting, and a sound embodying an endless optimism, even in its most sentimental songs. This is the kind of album you’ll listen to over and over, because it adapts to every phase, every mood, each lyric laced with heart-wrenching and, sometimes, lighthearted simplicity. It’s a museum-worthy, American-quilt-apple-pie comfort, perfect for our times right now. “I’ve never made a record that was more fun to make and as easy and gratifying than this one,” Andrew says.

In speaking with these two old friends of 25 years, their mutual respect and devotion to their craft is at the forefront. They’d parted ways amicably to do their own thing around 2000, but came together nearly two decades later to make the album that would eventually turn out to be These 13. As Jimbo describes in his signature southern drawl: “I went onto my path and [Andrew] went onto [his] path, and all the great records [he] made. It’s not like we were estranged, but we just didn’t talk anymore until fairly recently.” They started the new album in 2018 and completed it just before quarantine 2020, and filmed a documentary (via Thirty Tigers) about the process. The album is being released today.

In light of Squirrel Nut Zippers’ swinging, dance-ready beats, when asked how they achieved such a beautiful, melodic, heart-wrenching collection with These 13, with the folksy air of hopeful melancholy, Jimbo says: “As one of my mentors taught me…fun sticks to tape.” He laughs. “So does misery.”

What was your first impression when you met each other?

Jimbo Mathus: I just thought he was a brilliant musician, and there was obviously a lot there. He was a bit younger than me and I had an established group going, but I immediately just recognized in him some incredible talent and immediately tried to bring him into my family, into my band at that time. That was my first impression.

Andrew Bird: I was pretty fresh out of music school at Northwestern. It’s slightly more like a cerebral buttoned-up kind of atmosphere. I saw the difference in Black Mountain and Jimbo. I was already into this early jazz stuff and I thought, “Here’s a living example of what I thought was lost art.” He’s like a mentor to me, a living musician that I really looked up to and he really set me on a course.

JM: We talked yesterday. Andrew said, “I wonder what would happen if we hadn’t met.” That would be interesting to postulate.

What do you think would have happened if you hadn’t met?

JM: We met each other at the perfect times. We really did. We did so much work together. We were just tabulating yesterday, seven records in four years. A lot of them are iconic records, and most of them were down in New Orleans.

AB: Up in Chicago, there was a lot of talk about music. It just got kind of frustrating. I was just so ready to jump in and participate. Then meeting Jimbo is just like, there wasn’t much talk. We just got right to it. Hanging with these eccentric Southern characters and I’m 23 years old, I’m in New Orleans and music just everywhere, part of everyday life. I was really glad I got exposed to that.

What made you reconnect?

JM: We kind of forged each other’s future at that time. We went off on the trail and then Andrew reached out to me starting about two years ago and said, “Hey, let’s get together and just do some duo performing and writing.”

AB: I always had back of my mind, I wanted to do a super stripped-down duo fiddle guitar thing with Jimbo I had been following what Jimbo was doing. I saw a need for people to really hear some of the nuance and this lost vernacular that he still has, is keeping alive that I want to expose that in a particular way without any other musicians. You can really hear — just some of the things that he does with his feel and his phrasing.

When you reconnected, did you know what sound you were going for? It’s so different from Squirrel Nut Zippers.

JM: It was just a reconnection on folk music, the rich music we both learned and appreciated such as Charley Patton, for example. You can go listen to him in the ’30s. The rural Mississippi musician that I had close ties to. Just hear the gears of American music being forged. You can hear the whole future of everything that you hear now in his recordings. Andrew and I both shared that then. It wasn’t a thing we brought to recordings per se.

AB: Jimbo kept sending me songs. There were probably 20 to 30 bits and pieces you’d send me, and I was trying to steer it towards more in the Charley Patton direction. It was full of range from traditional country type to early country. I was trying to get a good balance of the country blues and then the country churchy stuff. I didn’t know when we started this project that we were going to write so much together. Eighty percent of the record is Jimbo firing off a couple verses, and then if I really heard it, I’d go with my first response. Neither of us have really done anything like that before.

How do you guys describe the music?

JM: It’s American folk music, I would say. What do you think, Bird?

AB: Yes. It’s original, but the feet are firmly planted in particular era, I would say pre-war and post-war American music. Post-black and white. I’d say my first template for this was Mississippi Sheiks, which is a group that made sense to reference because it’s fiddle and guitar. They were a group in the ’30s. I’d say Charley Patton, Mississippi Sheiks, Carter Family. Besides “Sweet Oblivion,” “Beat Still My Heart,” and “Bell Witch” everything is a collaborative writing process.

“Three White Horses” is an old song of mine, and it’s been for years. I had Jimbo sing that, and then he spontaneously while recording it, drew in a new verse about laying me down with a golden chain. “Beat Still My Heart” which is a beautiful song of Jimbo’s that I took the singing duties on. It has always been that agrarian-urban conflict in American life. It’s especially raw and laid bare in the last four, five years. I think the songs are addressing that. The “Red Velvet Rope”, “Poor Lost Souls”. There’s some dialogue going on between those two worlds.

The album was finished in early 2020. Did you finish before quarantine?

AB: Just before. Late January, early February we did our last session. We did about half the songs in ’18 and the other half in 2020. We just squeezed in that session before it all…

JM: In the interim, we were sending songs back and forth. We saw how the record was shaping up, I think. We had more of a goal to write and to contribute the titles, the themes, as Andrew was saying. We tightened it up.

The album is These 13. Is 13 lucky for you guys?

JM: Yes. [Chuckles.] Not for Craps games though. [Laughs.] Not for dice.

Were you going for 13 tracks?

AB: I said to Jimbo, because he has this Faulkner connection, living around Oxford…and he’s written songs based on Faulkner characters. I thought, since this album has this deep Southern connection that, “Is there a Faulkner reference that would make a good title?” There’s a rare collection of short stories, early collection of Faulkner short stories called These 13. Yes, and we happen to have 13 songs so…

JM: The lightbulb went off in my head. Andrew suggesting that Faulkner reference brought up These 13, which is the perfect title. I love titles. It’s a great title. It’s the perfect title. Even the title was a collaboration.

AB: The working title was Pretty Rough.

Do you have a favorite song on the album?

JM: I really like “Jack O’ Diamonds.” That’s my favorite.

AB: I like that too, and I like “Burn the Honky Tonk” because it’s a classic country crooner thing…I can’t write songs that let me sing like that. It brought some kind of resonance out of my voice, like a Marty Robbins thing almost, which I love, but I myself can never seem to write a song for myself to sing that well, that can access that part of my voice. That sense of joy, every time I play that song, I feel the resonance. “Dig Up the Hatchet” was nice…I guess that one came together.

There’s a beautiful simplicity to the whole album.

JM: My favorite songwriters are not the complex ones. I like the simple ones. I like the Carter Family. I’d rather listen to Waylon Jennings than Bob Dylan or The Rolling Stones. I like simple songs.

AB: In Americana music there is a player, hotshot instrumentalist tradition, bluegrass or just the Nashville thing of all these guys that can just shred. Every time there’d be a room for a fiddle solo I was just like, “I don’t want to win any awards here, I just want to play.” It just distinguishes itself by not trying to win in what you play, and that’s something I value more and more as a songwriter as I get older is just, it’s in the performance, it’s in the phrasing. It’s not in the impressive chord progression or tricky little turnaround.

JM: I think we just both sing with our natural voices on this, which is quite a thing for a recording singer to say because usually you’re most critical of your own voice. I think Andrew and I can both listen to this, and people close to me, my wife and close friends go, “That’s your best voice I’ve ever heard you sing in.” It’s most honest. Even though we may be doing some characters on the record, the honest moments are the real tear-jerkers.

Do you consider yourself storytellers?

AB: It’s not a simple answer for me because narrative has never been a huge goal for me in songwriting. I want you to know what this song is about when it’s over, but…you only have three minutes, and that’s just not enough for character development [Chuckles] sometimes. It’s just enough for an impression or a little tip of the iceberg of sure you could write a novel about what’s being introduced in a song. I think balladry is a whole different art form…

JM: You got short stories and then you got novels. I guess when I say yes for that, it’s a short story. Like These 13, okay, we could go more, but that feels like that’s a part of the deep South thing, you are a storyteller, even if you leave a lot to the imagination of your listener. No, I’m not going to do 13 verses of like a bardic recitation, but people look to us, I think, to be storytellers, even if it’s a story they tell themselves too, in that regard.