Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love, 2019, 1 hour 42 minutes.

Directed by Nick Broomfield.

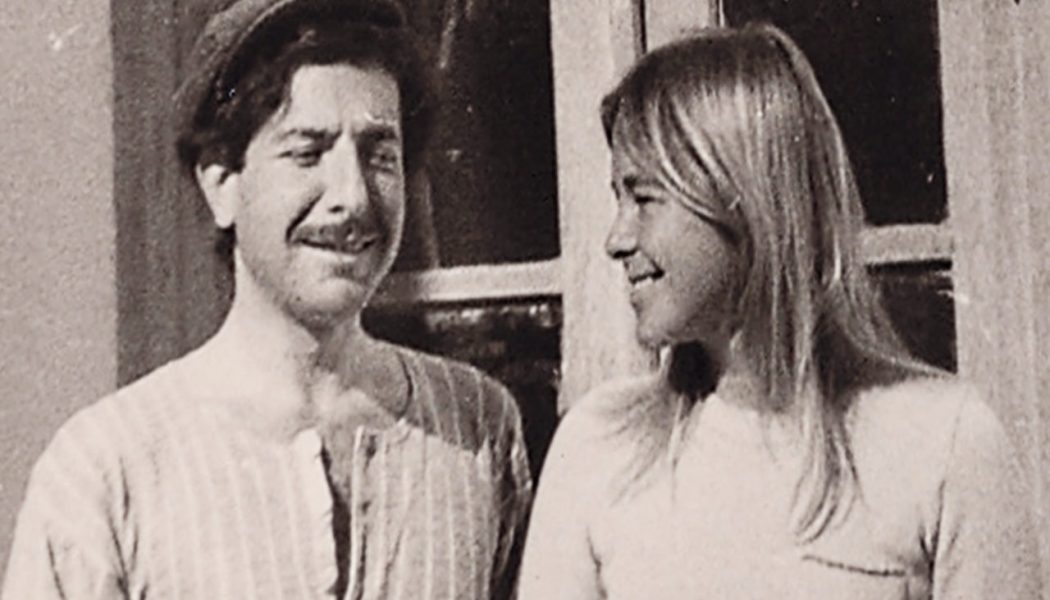

“Dearest Marianne,” Leonard Cohen writes to Marianne as she’s dying in a hospital bed, “I’m just a little behind you, close enough to take your hand.” And so begins the elegiac and hauntingly beautiful 2019 documentary, Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love. The film is a jagged sort of love story about Leonard and his Norwegian muse. Because Broomfield was Marianne Ihlen’s lifelong friend (and he adds, her lover on Hydra) the documentary is a magical memory tour that includes personal archival film, photos, and voiceovers of Marianne, Leonard, and the director too.

Like a Harold Pinter play that begins at the end of the story and moves backwards in time, Marianne and Leonard transits from Marianne’s hospital room in Oslo in 2016 to the bohemian playland of Hydra in the ’60s. Then it was possible to live on less than a thousand dollars a year. The island became a magnet for real bohos — writers, artists, and poets who were drawn to a speciously simple existence where donkeys were (and still are) the local mode of transportation. Against a backdrop of whitewashed dwellings and cerulean blue sky and sea, the film recounts how ex-pat life was a long party of swapped partners, drugs, and dinners of fresh-caught fish and a few too many glasses of Ouzo. The artists, as artists are apt to do, feasted on one another and the youth and beauty of their muses. Hence, there were casualties: neglected children, overdoses, broken hearts that didn’t heal, suicides.

Marianne and Leonard is an exceedingly intimate film. It’s like a Leonard Cohen song — he makes a window into our soul — and shares his soul with us too. The film includes a treasure trove of original footage from the period Leonard calls his “old life.” We see him in virile bare-chested prime. We watch Marianne dive off a boat or standing like a bronzed goddess, staring out at Homer’s wine dark sea. We see her son “Little” Axel (named after his father Axel, Marianne’s husband). We’re told Little Axel went to India, took too many drugs, and subsequently was institutionalized for the remainder of his life. Present in their absence are people in Leonard’s life that we don’t hear from, yet another reminder that we’re privy to only part of the story. Suzanne Elrod, the mother of Leonard’s two children, doesn’t appear, nor do Adam and Lorca themselves. In a candid interview with Aviva Layton, ex-wife of famous Canadian poet Irving Layton (and Leonard’s good friend), we learn that Suzanne flew to Hydra to evict Marianne and Little Axel from the Cohen abode. He had let Marianne stay on after the affair was over.

The film double underscores that Marianne was Leonard’s greatest muse. That is, before she was discarded in the name of art. Before Leonard’s fame took him up, up and away. Of all the artists on Hydra in the heady ’60s, it was Leonard who became a kind of cult god himself, ascending to musical Mount Olympus. Adored by fans, the guru-poet-Zen monk sang his life in poetic story-songs with melodies often inflected by mandolin modes influenced by his Judaic upbringing and his mother’s Russian heritage. In his 80s, Cohen toured the world giving concerts to legions of fans who laughed and cried, like the lyrics in his song, and cheered him on with adoration. In later life, Leonard traveled in style between gigs with a private jet and entourage of 59. He earned upwards of 14 million dollars a year. A goosebump making moment in the film is watching Marianne’s face as she sits front row at a concert while he sings her song. Along with the rest of the audience, who like most of his fans know the lyrics by heart, she sings the chorus to “So long, Marianne.”

But before he was our Leonard Cohen, the film reminds us he was Marianne’s lover. He was an impoverished Canadian poet, albeit from an affluent Montreal family. He drank too much, took speed and typed three good pages a day, and Marianne brought him a sandwich for lunch. Perhaps Marianne was too nourishing and supportive, as the film suggests — a kind of martyr-muse. She recalls, “I was his Greek muse who sat at his feet.” Indeed, the muses with staying power are elusive and just beyond arm’s length out of reach, a glimpse away.

Both Leonard and Marianne’s voiceovers run throughout the film, as though they’re sharing something precious of their past and turning the pages of an old photo album just for us. Leonard says, “What I loved in my old life, I haven’t forgotten.” Marianne never forgot him, and the film tells us she had “the compartment of her heart that was always married to Leonard.” For those of us who love his music, we’ll never forget him. He sang his joy and pain and we weren’t alone. He’ll always be our Leonard Cohen.