If 2020 brought anything good, it’s another high point in the unimaginable meteoric rise in record sales. Sales grew 46% from 2019, with 27.5 million LPs sold in the United States last year, vinyl outsold CDs for the first time since the 1980s — when vinyl started losing to its polycarbonate plastic counterpart. It’s clear now that the old medium for listening to music isn’t just for the nostalgic or hipster purists that are obsessed with sound quality. It’s becoming a mainstream way to collect and consume music.

But why?

When it comes to technology, we’re all about moving forward rapidly, staying on the cutting edge. So, why, then, when the biggest music catalog on Earth sits just a couple of touches away on our smart devices, are we returning to a century-old medium?

For many, it may just be a desire for something physical. That’s what Joey Cahill, owner of Wanna Hear It Records outside Boston, thinks at least, “A lot of people coming in here just want to be able to hold something.”

It’s perhaps a reaction to our increasingly online lives where everything is borrowed or leased through streaming services, and a fear that we won’t have anything to pass on to our children. After all, there’s no stronger motivation than the fear of death.

Wanna Hear It Records opened in the middle of the pandemic in December 2020, and to the surprise of many, including Cahill, has been doing well for themselves. Lines on the weekends are commonplace, and their Record Store Day celebration had one stretching around the block for the entire day.

“We’ve been really lucky,” Cahill says. “The community came out for us. It was also the perfect time to open a record store. I get so many people coming in here talking about how they’ve just picked this up as a new hobby. Something to fill the time while they were stuck at home.”

Jeffrey Smith of Discogs Marketplace, told me via email they experienced a similar surprising increase in sales. “Quarantine has undoubtedly played a role in the dramatic rise through 2020. We’ve heard numerous stories from people turning towards their record collection for connection and comfort during unsettling times,” Smith writes.

Despite their giant catalogs, streaming services offer quite a sterile listening experience when compared to an LP. The album art is small, music is crammed into playlists without say from the artist, and your feed is endlessly filled with lackluster AI-driven recommendations. Choosing the proper records, ripping off the cellophane wrapping, admiring the cover art, sliding the record out, browsing the liner notes, and then dropping the needle onto it, offers an objectively more deliberate and more immersive auditory adventure.

And it can’t be forgotten how artists have been treated by those streaming companies. Any checked-in music listener will know that their subscription fee likely isn’t paying for the roof over their favorite artist’s head.

Concert revenue has tanked due to the pandemic so the best way to show support is by buying merchandise, including records. “In a lot of ways, I’m reminded of the Napster era,” Cahill says. “People would say ‘well, I downloaded the track off Napster, but I went to their show and bought a T-shirt.”

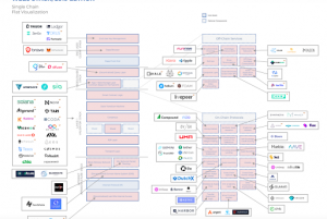

This isn’t to say that record collectors are Luddites. In fact, the boom in vinyl sales has been partly driven by a relatively new online infrastructure that has helped smaller artists and local record stores (nowadays, all we have left are local ones) get their merchandise onto the digital shelf. Bandcamp has long allowed their artists to sell merchandise, and over the pandemic have encouraged them to put up more for sale by incorporating Bandcamp Fridays where they waive their cut of the sale so 100% goes solely to the artist.

But undeniably the biggest player to have sparked this technological regression is the online marketplace Discogs, which allows shops and individual sellers to post their record collections for sale.

Smith told me that last year alone, Discogs helped sellers facilitate the sale of 12 million records globally! “Vinyl demand has been growing steadily for well over a decade,” he writes. “The spike that revealed itself in 2020 during the pandemic is more significant than vinyl demand…it’s the seismic shift to e-commerce. The scale has tipped.”

This is where we enter a sort of chicken-or-the-egg dilemma. Cahill points out that many of the top 40 artists have begun pressing vinyl again. “What was the new Taylor Swift album? Evermore? Everytime we get a new shipment of that, it goes in a day — two at the most.”

It’s no longer older and niche artists. The likes of Swift, Billie Eilish and Harry Styles are doing big numbers. Forbes reported in June 2021 that Evermore sold 102,000 vinyl copies in a single week, shattering Jack White’s record for most records sold in a week of 40,000. Eilish sold 113,000 LPs in 2019 and Styles’ Fine Line moved 232,000 records.

Eleven years ago, these numbers would have been unfathomable. Back then the highest selling record was still The Beatles’ Abbey Road (35,000 copies), and the runners-up were indie rock acts Arcade Fire (18,800 copies) and The Black Keys (18,400 copies), two groups with much smaller profiles than Swift.

It is somewhat telling that the acts that followed up The Beatles’ sales were 80th and 79th respectively on the Billboard 2010 end-of-the-year chart.

It seems that the majority of vinyl fans a decade ago were still into artists just outside of the spotlight. These days though, everyone from Gen Z to the grizzled Deadhead is going crate digging, and with a decade and a half of growth under its belt, it seems that vinyl will continue to spin.