On March 9, 1819, a supremely gifted musician named Francis “Frank” Johnson played a concert at the Masonic Hall on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia. Johnson and his bandmates were free Black men; the audience was white and well-to-do. The building was a monumental Gothic Revival masterpiece with a towering steeple.

Johnson, a 26-year-old composer and multi-instrumentalist, was already a sensation in Philadelphia. A book about the city published that year described him as the “leader of the band at all balls” and “inventor-general of cotillions,” a dance craze that was overtaking the city. The author, Robert Waln, a former U.S. representative from Pennsylvania, also marveled at Johnson’s flair for reinventing a sentimental song into an irresistible, foot-stomping jig or reel.

At some point during the show, the hall caught fire. The flames climbed up through the walls, and the mighty steeple collapsed, though no one was hurt or killed. And while the fire was started by a newly installed gas jet mounted too close to a flammable curtain, many Philadelphians enjoyed speculating that Frank Johnson’s “hot music” had ignited the blaze.

“Hotness” is a quality often associated with ragtime and jazz—Louis Armstrong’s first bands in the 1920s were called the Hot Five and Hot Seven—and it derives from making the rhythm more propulsive while stretching out certain notes. Was Johnson playing an early prototype of jazz, a century before its recognized birth in New Orleans?

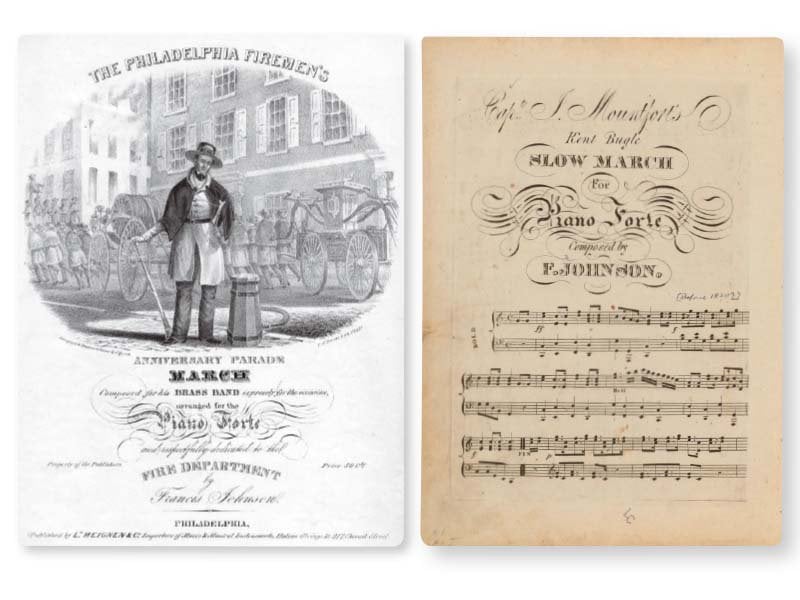

Experts are divided on that question, but all agree that Johnson was a major figure in early American music. Renowned for his inventive compositions and his virtuosity on wind and string instruments as well as the pianoforte, he broke through racial barriers, becoming the first Black musician to have his sheet music published, run a training school for other Black musicians and tour widely in the United States. And in 1837, he was the first Black American musician to take a band to Europe, where some historians say he played for Queen Victoria.

Johnson was famous all over the United States, as well as in Canada and Great Britain, but he was almost completely forgotten during the 20th century. Now, his star is rising again as musicians dust off Johnson’s compositions in an effort to bring his dazzling music back into the culture.

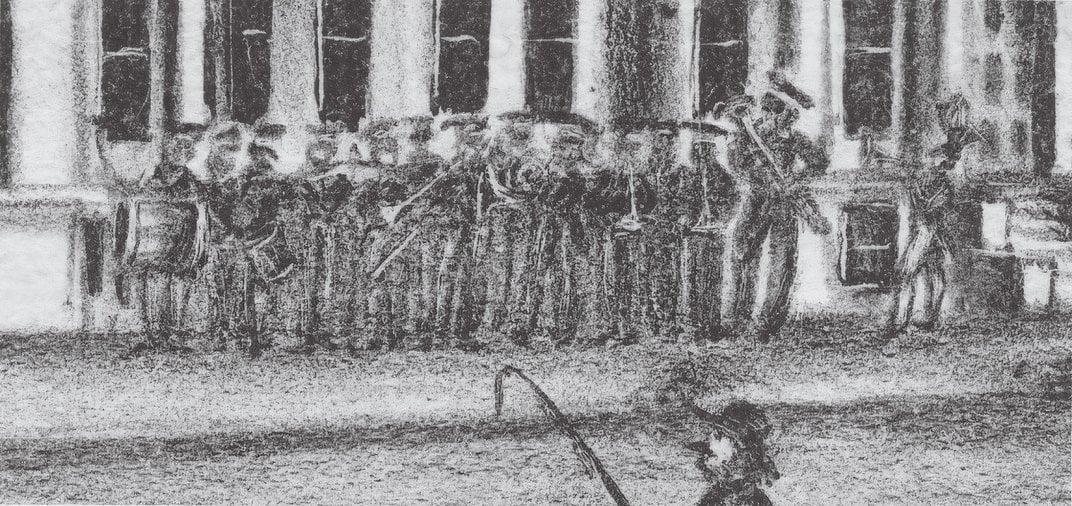

Rodney Marsalis, from the illustrious New Orleans jazz family, first heard about Johnson upon moving to Philadelphia in 2006 and “just fell down the rabbit hole with this guy.” As Marsalis learned, Johnson had more than 200 compositions published, including cotillions, quadrilles, waltzes, reels, operatic airs, military marches and quicksteps. Marsalis, a trumpeter, was particularly struck by the composer’s ability to appeal across racial lines: Johnson was the first Black musician to perform in integrated concerts with white musicians. “That really drew me to him,” Marsalis says. “He believed there’s one human race and music is the thing that brings us together. That’s why it’s so important to bring him back to life.”

Little is known about Johnson’s early years. It is often stated without evidence that he was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique. More persuasive is a baptismal certificate from St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Philadelphia for a Francis Johnson, born June 16, 1792. The church was in the Society Hill neighborhood, where Johnson lived as a teenager and adult in a free Black community, whose members were welcomed by the white rectors at St. Paul’s.

By his 15th birthday, having mastered the flute, piccolo, violin, bugle and pianoforte, Johnson was playing in Philadelphia taverns and was soon hired as a fiddler at a predominantly white social venue called the Exchange Coffee House in an old mansion on Third Street, where he built up a huge following. His fans delighted at the breadth of his repertoire and his highly danceable revamps of older songs. In 1810, when Johnson was 18, George Willig, a Philadelphia-based music publisher, heard him play at the coffee house and asked him to write some original music. The result was “Bingham’s Cotillion,” a piece named after William Bingham, the former owner of the coffee house building. It was the first musical composition published by a Black American. That same year, a new instrument called the keyed bugle arrived in Philadelphia. It was tough to play, with finger-operated levers that opened and closed the tone holes, but it afforded much greater possibilities for musical expression.

After several years of practice, Johnson was the nation’s foremost master of the keyed bugle and developed a technique of singing through the horn while playing it. When he performed his composition “Philadelphia Fireman’s Quadrille,” audiences were astonished to hear his bugle cry out, “Fire!” He could also impersonate an ice cream vendor hawking his wares and use his flute to mimic a canary.

Johnson explored all the musical forms of his day, including Mozart’s concertos, Irish jigs and Black sacred music. He wrote a series of works in the Spanish-Andalusian style, composed military marches and led a military band of free Black musicians.

One of Johnson’s most ardent admirers today is Homer Jackson, a visual artist who heads the nonprofit Philadelphia Jazz Project and has used public spaces to stage pop-up concerts of Johnson’s work. “When you look at the pictures of Frank Johnson, he looks so beautifully composed. Supremely confident,” Jackson says. “He reminds me of Miles Davis that way.”

Jackson does see Johnson’s music as a precursor of jazz. “He definitely wasn’t composing jazz, but the notes on the page are not the whole story,” he says. “When he performed, people described his playing as inventive, with embellishments, distortions and soul-stirring energy. When we performed his pieces, it was so easy to see how you could ‘get happy’ with that music, in the African American way, and make it swing.”

In 1819, Johnson married Helen Appo, a Society Hill seamstress who became a successful costumer, milliner and tailor. It appears the couple had no children. When he wasn’t playing military or society events—or practicing or composing—he would give lessons in their house. One student recalled that Johnson’s music room was filled with instruments, with thousands of compositions on the shelves and, in one corner, “an armed composing chair, with pen and inkhorn ready, and some gallopades and waltzes half finished.”

To expand his musical knowledge—and, no doubt, to seek adventure—Johnson decided to go to Europe. In November 1837, after a series of fundraising concerts in Philadelphia, the four-piece Francis Johnson Band sailed to Liverpool, England. No one had any idea how Europeans would respond to Black American musicians. When they got to London, Johnson rented a performance space at the Argyll Rooms on Regent Street and announced a series of twice-daily concerts in the newspapers: “Great Novelty … First time in Europe of the self-taught men of Color.” To intensely curious crowds, they played selections from Rossini, Mozart and Bellini, along with Johnson’s original compositions and his new arrangement of “God Save the Queen.” One attendee said the band was equal to the best musicians in Europe.

After a stint in Paris and a summit with Austrian composer Johann Strauss in London, Johnson returned to the U.S. His homecoming concerts, held at the Philadelphia Museum in the Christmas week of 1838, were a smash, drawing crowds of 3,500 people for several evenings in a row, with many more turned away at the door. He was a beloved, celebrated figure in Philadelphia, in high demand for white society events, but Johnson wanted to break new boundaries and see new sights. In 1842 and 1843, Johnson and nine Black band members embarked on the longest tour undertaken by any American musicians in the early to mid-19th century, and it turned him into a national celebrity. They traveled on riverboats and stagecoaches, and drew record crowds and rapturous reviews in New York, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Virginia and Pennsylvania. They also clashed intermittently with the forces of white supremacy.

In St. Louis in December 1842, they were served with warrants and charged with being “Free Negros within the State of Missouri without a license.” A local firemen’s association, which had hired Johnson’s band to perform at its anniversary ball, engaged a lawyer to defend the musicians, who played sold-out concerts every night as motions and appeals were filed in court. When the circuit court adjourned for its Christmas break without reaching a verdict, the band departed for Kentucky and Ohio. In Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, they faced racist violence. A mob assembled outside the concert venue and attacked the band members in the streets, hurling stones, brickbats, rotten eggs and racial epithets. Several musicians were badly hurt, but the band showed its mettle by playing the second night of its engagement.

Returning home to Philadelphia, Johnson resumed his normal schedule of playing, composing and teaching until late March 1844, when he fell desperately ill. Two weeks later, on April 6, he died at 51 from a ruptured aortic aneurysm. His funeral drew one of the largest crowds of mourners ever seen in Philadelphia, and his band played a dirge that Johnson had composed 12 years earlier. William Henry Fry, a composer, music critic and editor of Philadelphia’s Public Ledger newspaper, delivered the eulogy. “His talents as a musician rendered him famous all over the Union, and in that portion of Europe which he had visited, while his kindness of heart and gentleness of demeanor endeared him to his own people, and caused him to be universally respected in this country.”

Johnson’s slide into obscurity was not immediate. Twenty years after his death, a historian named Louis Madeira noted Johnson’s “very considerable celebrity” and mastery of the keyed bugle. In 1884, in a history of Philadelphia, Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott similarly highlighted Johnson’s fame and importance to American music. But then, according to Johnson’s biographer, Charles K. Jones, “all 19th-century references to him were quietly swept from the pages of 20th-century editions of standard music history books for more than six decades.” In the early 1960s, Richard J. Wolfe, a musicologist, rediscovered Johnson’s story while researching his three-volume Secular Music in America. Still, among the general public, Johnson remained about as obscure as ever.

Today, though, the Philadelphia-based movement to restore Johnson’s reputation proceeds apace. Rodney Marsalis is performing entire concerts of Johnson’s music with his brass band, and the Library Company of Philadelphia staged a recent exhibition about Johnson; Brian Farrow, a musician and historian, has been performing some of the great composer’s music. And Homer Jackson is planning further tributes—not just to Johnson but also to the free Black musicians whom Johnson schooled in his style of playing. Asked how folks should remember Johnson today, Jackson says, “As a tributary of jazz and an American superstar.”

Recommended Videos