“The state’s attempted silencing [of dissent] took four main forms,” wrote Gwen Ansell in her book Soweto Blues: Jazz, Popular Music, and Politics in South Africa. “The closing down of the last spaces for expression; the attempt to replace urban and politically aware discourses with synthetic, conservative, tribal substitutes; the creation of distractions; and the driving of increasing numbers into exile.”

As-Shams, the label established by Rashid Vally in 1973, became a vital platform for the musicians who stayed behind. The label first began taking shape in the basement of a small shop on Kort Street in downtown Johannesburg that was owned by Vally’s father. “Kohinoor had begun as a predominantly general store with a little corner my dad allocated for me to ply my album trade,” explains Vally. The shop soon became an important meeting point for South African musicians, whose outlets were restricted to a few key venues such as Dorkay House and The Pelican in Johannesburg and Club Galaxy in Cape Town. In 1970, Valley drew on the connections he’d made in the store to form a label called Soultown and release the Cape Jazz LP Early Mart by drummer Gideon “Mgibe” Nxumalo’s big band.

The album caught the attention of legendary pianist Abdullah Ibrahim, who approached Vally to release the follow-up to his monumental solo LP African Piano. Recorded at Gallo Studios, Peace, with Victor Ntoni on bass and Nelson Magwaza, drums, was the first of three LPs the pianist recorded for Soultown.

With resistance in the townships reaching a boiling point in the lead up to the Soweto Uprising of 1976, Ibrahim suggested Vally change the label’s name to something that reflected the times. As-Shams—or, The Sun—debuted with a record that came about more or less by accident. Vally and Ibrahim were recording in a Cape Town studio when, “Abdullah’s attention was diverted to an upright piano that had drawing pins attached to the hammerheads,” recalls Vally. “This piano was used to record commercial jingles, [and the pins gave it] almost a harpsichord sound. He started playing around and called the horn players to join in and the first strains of ‘Mannenberg’ began to emerge.”

A shrewd businessman, Vally struck up the first of many distribution deals with the influential South African major label Gallo after “Mannenberg” became an anthem for the anti-apartheid movement. Its success became a springboard for As-Shams, whose catalog would grow to include jazz, soul, funk, and fusion often with covert—or not-so-covert—political and social messages. In recent years, via a partnership with Cape Town label Sharp-Flat, As-Shams has been revived, and has been slowly reissuing long-sought-after LPs recorded during the darkest days of apartheid. Forty years after it was founded, it’s also releasing its first-ever compilation As-Shams Archive Vol. 1: South African Jazz, Funk & Soul 1975-1982, which serves as a tribute to the resilience and bravery of the players who stayed in South Africa under apartheid.

“It was very hard to make a career out of jazz during the apartheid era, because your audience were curtailed by the Group Areas Act,” says Sharp-Flat’s Calum MacNaughton. “There weren’t many spaces where jazz performers could try tap into a middle class white jazz audience. So to make a living was very hard and these guys had to really hustle.” To celebrate that spirit of endurance—as well as the label’s recent reactivation—here are just a few titles to start you on your journey.

Pat Matshikiza & Kippie Moeketsi

Tshona!

Unlike the other members of the Jazz Epistles—who released the first South African bebop LP in the late ‘50s—alto saxophonist Kippie Moeketsi chose to stay in his home country, eventually becoming a legend of South African jazz. Moeketsi first worked with Eastern Cape pianist Pat Matshikiza in the group The Jazz Dazzlers in the mid-‘60s. Here, supported by the rhythm section of Sipho Mabuse and Alec Khaoli (of Soweto Soul group The Beaters), as well as guest saxophonist Basil Coetzee, they recorded one of the milestones of mid-‘70s South African jazz. Composed by Moeketsi and built around an infectious piano line by Matshikiza and soaring saxophone soloing by Moeketsi and Coetzee, “Umgababa” is typical of the joyous music the two ex-Jazz Dazzlers made together.

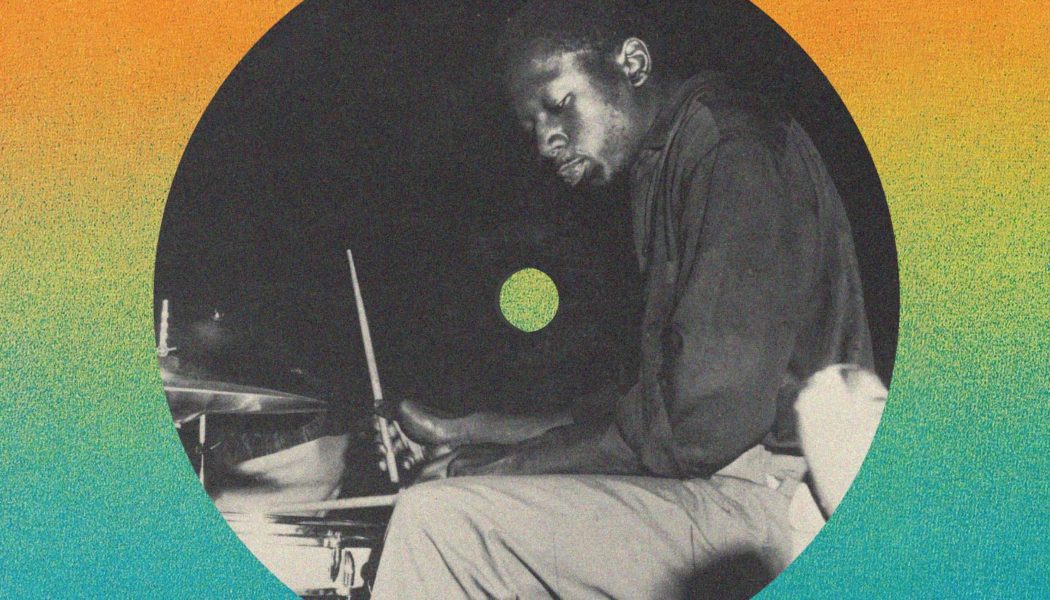

Dick Khoza

Chapita

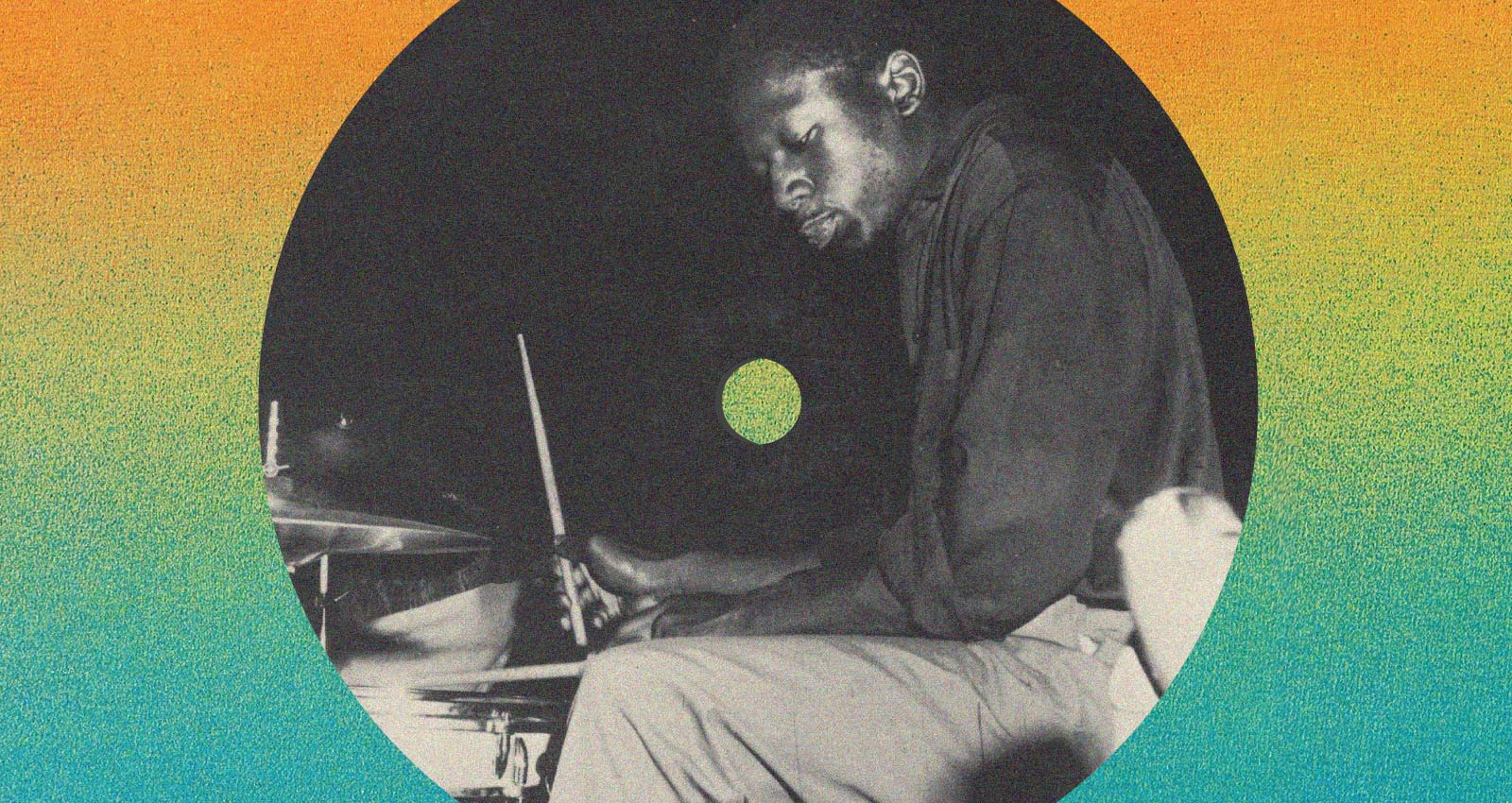

Raised in Durban, drummer Dick Khoza became a regular session man at Dorkay House and The Pelican when he moved to Johannesburg in the ‘60s. As talent scout and stage manager, he formed friendships with musicians like pianist Tete Mbambisa the As-Shams artist on whose LP Tete’s Big Sound Khoza appeared. In the year of the Soweto Uprising, he traveled back home to Malawi, returning to South Africa inspired. The result was the almighty Afrocentric jazz album Chapita, recorded with a band of musicians from the Pelican house band who were given free rein by producer Rashid Vally. The storming Afrofunk of “Chapita” tells the story of a meeting between two migrants in the city—something of an autobiographical tale for the Malawi-born Khoza. The track had often closed out sessions at The Pelican, and was now a statement of intent on what would become one of As-Shams’ best-known LPs.

The Beaters

Harari

After Gideon “Mgibe” Nxumalo’s Early-Mart, Soultown released a string of funk and soul 7-inches by bands like the Elations and Dynamics—groups that were part of the Soweto Soul scene when youths from the townships were finding inspiration in Black America. Emerging from that scene, The Beaters had toured Zimbabwe in 1974 where, to quote the group’s drummer Sipho Mabuse, they discovered their “African-ness”—the infectious rhythms and music of the continent. We came back home inspired.” The result was Harari, recorded for As-Shams in 1975, which included the brooding Afrofunk of the title track. The band soon renamed themselves Harari, and recorded the Afro-rock LP Rufaro Happiness for As-Shams a year later.

Pat Matshikiza

Sikiza Matshikiza

Patrick Vuyo Matshikiza moved to Johannesburg from the Eastern Cape in 1962, where he joined the jazz community of Dorkay House and met players like Kippie Moeketsi. His debut under his own name for As-Shams was recorded shortly after the Tshona! session with Moeketsi. The unmistakable Cape Jazz piano forms the backbone of this LP, but also up front are the jazz guitar licks of Sandile Shange, the tenor sax of Duke Makasi, the bass of Sipho Gumede, and the drums of Gilbert Mathews. The band members also went by the name Spirits Rejoice, whose sought-after 1977 album African Spaces was recently reissued by Matsuli, the first label to dig into the As-Shams back catalog. One of South Africa’s greatest pianists—next to Abdullah Ibrahim—Matshikiza also appeared on Kippie Moeketsi’s album Blue Stompin’, released on As-Shams in 1977.

Sathima Bea Benjamin

African Songbird

One of the great voices in jazz, Cape Town-born Bea Benjamin joined Abdullah Ibrahim’s trio in 1960, traveling with the group to Europe where she married the pianist. Serious sessions followed, including with Ibrahim and Don Cherry on their Universal Silence tour. But it was with As-Shams that her full force was unleashed on the spiritual jazz masterpiece African Songbird, her debut recording after a number of albums had been shelved. Recorded with Ibrahim, Basil Coetzee, and a band that included three bass players and two drummers, the album opens with “Africa,” a spine-tingling dedication to her people (“I’ve been gone much too long, and I’m glad to say that I’m home to stay”). Right up there with the deepest Abbey Lincoln session, the album closes with the haunting a cappella “African Songbird.”

Black Disco

Night Express

Reissued by Matsuli in 2016, Black Disco’s Night Express was the brainchild of one Ismail “Pops” Mohamed. Raised in the East Rand to a Muslim father and mother of Xhosa and Khoisan heritage, Pops started his musical life amongst the jazz hierarchy at Dorkay House. But it was as a member of Soweto soul group The Dynamics that he got his break and picked up the influences you can hear throughout this LP. “I was listening to a lot of Timmy Thomas—I loved the track ‘Why Can’t We Live Together?‘—and I’d acquired a Yamaha organ to explore that kind of sound,” he told writer Gwen Ansell in the sleevenotes to the album’s 2016 reissue. In 1976, Pops invited saxophonist Basil Coetzee, bassist Sipho Gumede, and drummer Peter Morake into the Gallo Studios for one of As-Shams funkiest and most soulful releases. The standout track is the Coetzee-composed “Night Express,” a soaring 11-minute slab of spiritual modal jazz funk that carried a revolutionary message in the year of the Soweto uprising.

Movement In The City

Black Teardrops

After three Black Disco LPs for As-Shams, Pops Mohamed turned his mind to a new project to reflect the urgency of the times. “In 1979 when the political situation got worse, I decided to go underground and fight the system in my own way,” Pops Mohamed told me for the sleevenotes to the 2002 compilation Afrika Underground, Jazz Funk & Fusion Under Apartheid. That project was Movement In The City—Pops on Rhodes and acoustic piano; Basil Coetzee on flute; Robbie Jansen on alto sax and flute; Sipho Gumede on bass; and Roger Harry on drums. The group’s Calum MacNaughton, “conceptually grounded in the bleak social realism for As-Shams was, in the words of Calum MacNaughton, “conceptually grounded in the bleak social realism depicted on its photographic album…blending Cape jazz with funk and soul.” The follow-up was even more closely aligned with the movement for change from which the group took their name. One of the deepest and most poignant albums recorded for As-Shams. Black Teardrops was dedicated to those killed in the Soweto Uprising. The album closes with “Camel Walk,” a 14-minute piece of brooding and deeply affecting modal jazz.

Barney Rachabane

“Tegeni”/ “Mafuta”

A regular sideman for As-Shams who had appeared on some of the label’s biggest releases—including Tete Mbambisa’s Tete’s Big Sound and Kippie Moeketsi’s Blue Stompin,—Barney Rachabane never released an album of his own for the label. However, when Calum MacNaughton began researching the archive, he discovered that the alto saxophonist had actually recorded a number of unreleased tracks with a heavyweight band including pianist Bheki Mseleku and the Spirits Rejoice lineup. Recorded in 1978 the Rachabane compositions “Tegeni” and “Mafuta” are typical of the swinging Marabi-style jazz at which As-Shams excelled. This EP was released with the blessing of Rachabane’s family after his sad passing in 2021.