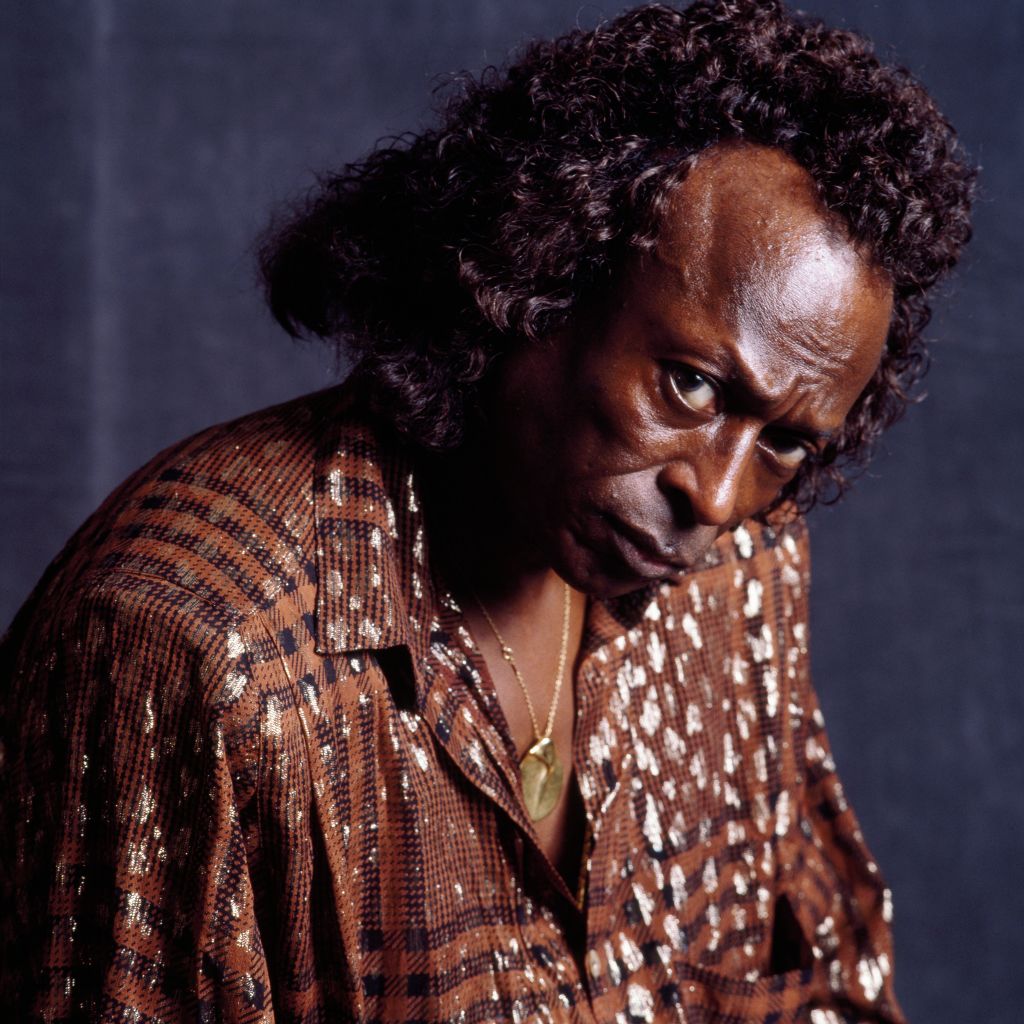

A version of this story originally appeared in the December 1991 issue of SPIN. We’ve republished it on what would have been Miles Davis’ 95th birthday.

I loved watching Harry Reasoner’s expression on 60 Minutes when Miles told him he felt there was nothing wrong with being a pimp: “Women liked me,” rasped the controversial, iconoclastic, horn-playing genius. Oh, Miles! I could hear women gasping from coast to coast! This man did speak his mind. I decided I finally had to get in touch with this gravelly-voiced musical messenger and get him to talk to me, even though the word was he wasn’t talking to anybody (not even to promote his just-released autobiography, Miles, for Simon and Schuster). And he is oh so difficult—authentic and stubborn. Good enough for me; I had to try.

Miles Davis was born on May 25, 1926, in Alton, Illinois. He grew up in East St. Louis where, at the age of 13, he began blowing his trumpet. But it was hearing Dizzy Gillespie’s trumpet and Charlie Parker’s saxophone that made Miles decide to be a musician. Arriving in New York in 1944 to study at Juilliard and to find Dizzy and Bird, Miles soon found that “the shit they was talking about was too ‘white’ for me.” He began hanging out on “the Street”—Fifty-second Street—the Three Deuces, the Onyx, and Kelly’s Stable, where a heavy jazz scene was happening and all points converged. He finally found Bird and Dizzy and the other legends of his musical bebop tribe. He quit school and began playing with Charlie Parker’s quintet. But soon Miles took his own direction, and, with musicians like Gil Evans, Gerry Mulligan, and Lee Konitz, a new, more complex style called cool jazz emerged.

Restless and searching, Miles moved again, this time away from cool jazz to proclaim the arrival of hard bop, recording with musicians such as Sonny Rollins and Thelonious Monk. With Kind of Blue in 1959, Miles moved on to modal jazz, which would become the conclusive style of the ’60s. His coterie for this decade included Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams. Miles added electronic instruments and ended up with a haunting, aggressive sound—improvisational, but rooted in rhythm. The musicians who worked with Miles during this period went on to form innovative rock groups such as the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Tony Williams’s Lifetime, Chick Corea’s Return to Forever, and Weather Report. In the ’70s, he used Indian table drums and sitar—he had replaced melody and harmony with a funky melange of rhythm and electronics.

In 1975 ill health forced Miles into a five-year retirement and led to a drug abuse relapse. When he returned in 1981, critics said he had become a “business.” One thing is certain, the human sound of Miles’s trumpet and his angry, innovative style is a permanent legacy to the music of America. His final appearance was at the Hollywood Bowl at the JVC Jazz Festival on August 25, 1991. He died in Santa Monica, California, a month later, on September 29. This interview, Thanksgiving 1989, was his last.

When I first called the Essex House, the hotel in New York’s Central Park where Miles lived, the operators were definitely on the job. “Yes, Jennifer Lee. You see, I met Mr. Davis, actually it was ten years ago with my ex-husband, Richard Pryor. He had had an operation.” I was put on hold for several moments. Suddenly I heard the famous rasping voice (after a throat operation he yelled too soon at someone, resulting in badly damaged vocal chords). Somehow it struck me how perfect that voice was. One had to lean into it, listening closely, attentively. Sexy yet chilling, it conjured up scenes of Regan in The Exorcist, swiveling on the bed giving her speeches from hell. And he spoke deliberately as well, slow, measured.

Miles Davis: Yeah?

SPIN: Miles, you probably don’t remember but Richard and I came to visit you. I think you had just had a gall bladder operation.

Davis: Could’ve been. They’ve taken so much out of me. Hang on a minute. [Silence for several moments.] Yeah.

SPIN: Miles, you were a very chic patient as I recall. Roaming around in your huge suite at New York Hospital in a stunning navy blue silk robe. You said the best thing to Richard.

Davis: What’d I say?

SPIN: [In my best imitation of the voice from hell:] “Richard, she’s fine. Are you going to marry the bitch?”

Davis: [The voice from hell laughs.] And did you?

SPIN: Yeah, I did. We did.

Davis: How was it?

SPIN: Divorce, heartbreak, Miles.

Davis: Hang on one minute.

SPIN: Miles, I read an excerpt from your book in Vanity Fair.

Davis: Writers are funny, man. [Perhaps a reference to Quincy Troupe, with whom he coauthored his autobiography.]

SPIN: Why?

Davis: If you say, “I don’t give a shit,” they have to say, “I don’t give a damn.”

SPIN: Well, Miles, I don’t think it’s easy to mess with your truth too much; it’s really strong stuff.

Davis: Yeah—you think so?

SPIN: Yeah, I do. Like that story of your cocaine dealer who couldn’t give you the dope without you paying her.

Davis: Well, she gave it to me, didn’t she?

SPIN: Yeah, after you pulled your cock out and her boyfriend was on the way up. . . Whew!

Davis: You’re funny. Are you in the lobby?

SPIN: I’m funny? No, I’m at home. Listen, Miles, before you say no, just think about it. What about a conversation, an interview? I’ll let you go. Just give it a thought.

Davis: When are you going to call again?

SPIN: Tomorrow night, same time.

I called back the following evening and Miles asked me to come meet him. “And bring something to drink if you drink. I don’t,” he said.

A couple of hours later, I rang the doorbell to Miles’s suite. After a few moments, he opened the door and studied me for a few seconds before asking me in. My first thought was, “transcendent.” The father of hip, the original cool cat. And predatory as hell.

He was a striking man. I was amazed at his youthful appearance. This man was over 60, yet his face held no time. He had on a pair of black and white tweed jodhpurs, a black and white sweater and a pair of black socks with little red dots. There was an immediate energy between us. He began by showing me around his suite. Then he pointed to a canvas on the floor. It was a large rectangular canvas with modern images dancing the length and width of it. Miles walked me slowly through the two large rooms with walls covered in art. His own, many framed, as well as many other works by up-and-coming artists which ran along the lines of ethnic folk art. Immediately I sensed his isolation amidst all this creativity. Here was a man who lived on and in his bed. With a TV in each room. The one in his sleeping area, I sensed, was always on, as it was this evening, nestled between some musical instruments and other electronic equipment. The vivid colors of all the low chairs and couches and tables, the wall-to-wall mirrors and the lighting, could easily be called “modern.” The tone of this environment felt early ’60s. Yet there was a naiveté to it as well. Piles of things all around. Exercise apparatus stood like weird pieces of sculpture, neglected and dusty. We settled in his sleeping area. He sat in his low-rider white chair and stared at the television; I sat on the edge of his low platform king-size bed.

Davis: How’s Richard?

SPIN: Not good.

Davis: Whadya mean?

SPIN: He’s sick.

Davis: With what?

SPIN: I’d rather not say.

Davis: What? Come on, tell me?

SPIN: Well, it’s not AIDS.

Davis: Is it palsy?

SPIN: MS.

Davis: Richard never calls me. I told him, “You don’t have to call me every day, just once a month.” It’s been three years.

SPIN: You know I worked with your wife, Cicely [Tyson], once, on Bustin’ Loose.

Davis: Ex-wife…. [They were divorced in 1987.]

SPIN: Miles, I know you don’t like to give interviews. I heard Simon and Schuster is mad at you for not promoting the book.

Davis: They are? You know why I don’t do interviews? Because more than one person shows up, they snoop around and ask stupid questions. That’s why. But Jennifer, I like you, that’s different.

SPIN: Thanks.

Davis: When do you want to do it?

SPIN: This weekend?

Davis: You should read my book.

SPIN: I’ve got to get it.

Davis: It’s in the other room; walk straight back, you’ll find it.

I returned with a copy of Miles. I opened the book and saw a picture of his mother. He pointed to the picture and tapping it several times said, “Good woman.”

“Did you enjoy doing this?” I said. “The book?” He shrugged. “No.”

His private portable phone rang. He picked it up and listened without speaking for several minutes and then handed it to me. I listened to someone playing saxophone at the other end, oblivious. “It’s one of my musicians,” he said, then took back the phone, listened for a few more moments, and without speaking placed the phone back into its holder. At this point the energy between us was translating into attraction.

“Well, I’ve got some research to do,” I said.

“How ’bout some soup?”

“Fine.”

With that Miles went into the kitchen, poured soup into two mugs, stuck them into a microwave, hit a few buttons, and, leaving, said, “You get ‘em.”

I stood staring at the neon digits click down, and while I’m no Julia Child, I suspected this was too long for soup to be nuked. I opened the door and took out the mugs. The broth had disappeared and the only thing left were the vegetables sitting at the bottom getting ready to burn. I took them in anyway and we ate the brothless soup. I was struck by the sweetness of this.

SPIN: Miles, what is that scar on your lip? Is it from the horn?

Davis: It’s from making love for so many years.

SPIN: What?

Davis: I’m kidding. It’s from the horn. Come here, let me show you. [He put his lips to mine and, using his tongue very lightly, acted as if he were blowing his horn.]

Davis: My embouchure.

SPIN: Oh, I see.

Davis: Can I ask you something?

SPIN: Sure.

Davis: May I touch your hair? [I leaned over and my short hair fell forward.] This is the most beautiful part of a woman [touching the back of my neck. I sat up, feeling a bit awkward.]

SPIN: [Noticing a small red medal on his sweater:] What’s this, Miles?

Davis: The Knights of Malta. They gave it to me.

SPIN: For what?

Davis: For my artistic contribution. ‘Cause I’m a genius. Jennifer, can I ask you something?

SPIN: What?

Davis: See this cream? Would you massage my feet for a while with it? They’re cramping, they hurt.

I did this for a few minutes. The cream was expensive and smelled wonderful, his feet were cold and gnarled. “What happened?” I asked.

“Car accident, broke my ankles. My Lamborghini.”

I decided it was time to go. I gave him a kiss goodbye, and he asked me to call him the following afternoon. I left carrying with me some emotion and thinking the entire evening was just like jazz.

I called the following afternoon.

SPIN: How you doing, Miles?

Davis: I don’t feel okay today. I got a lot of aches.

SPIN: Do you have the flu?

Davis: What?

SPIN: Miles, I haven’t read your book yet. What are you doing over the weekend? Friday?

Davis: I don’t know what I’m doing Friday. [Pause.] What are you doing now?

SPIN: Well, Miles, I haven’t read your book. I did get a copy of your Playboy interview, the one you did in 1962. They think that’s one of the best they’ve ever done.

Davis: I requested Alex Haley. They wanted to send me a white writer. I wouldn’t do it. I got him two thousand dollars for that. They messed with that, trying to make me sound angrier.

SPIN: What are you doing? Davis: Do you want to come over?

SPIN: You see your book—

Davis: I don’t want to force you. I’m hungry.

SPIN: I’ll see you in a little while.

Davis: Bring some food. Italian. Clam sauce.

I arrived in a bubble of garlic. Miles looked dashing and seemed glad to see me. I began to unpack the food—eggplant parmigiana, linguine with clam sauce, fettuccine, and Beaujolais. Miles stood watching me until the doorbell rang. It was his road manager, dropping off some movies. Miles pretended he couldn’t remember my name.

“Uh, let me see—Renée, right?”

I wasn’t laughing. “I’m Jennifer Lee, hello.” I turned my back and prepared our plates. They disappeared into the other room and I was mildly pissed. After a few moments, the roadie announced he was leaving. He turned at the door and said, smirking, “Nice meeting you, Renée.”

Under my breath, I said, “Goodbye, asshole.” Miles heard it.

“Oh, Jennifer, he’s a nice guy.”

“A little rude, Miles.”

“When we all went to Prince’s New Year’s Eve party, his girlfriend just sat and cried, ’cause he couldn’t dance.”

I just looked at him. I was still thinking about being called Renée.

“Don’t you think he’s funny?”

“Guess you had to be there.”

“Let’s eat in the other room.”

We sat at a little round table. I felt as if I were on a date. A large framed painting Miles had done stared at us.

SPIN: You know, your painting is like your music.

Davis: I know. I just figured that out. That’s my girlfriend. [He points to a striking-looking face in a painting.]

SPIN: She’s beautiful. What’s her name?

Davis: Bridget. She taught me how to draw a nude. I missed you last night. [Taking a pencil, he drew an abstract figure of a woman on a napkin and handed it to me. After dinner, we moved to the bright blue couch. Miles stretched out and put his head on my lap.]

SPIN: I thought of you, too [touching his very thick, long black hair].

Davis: Careful with my hair—it’s a weave so it hurts when you touch it. [I moved away.] Let’s watch a movie. [He put a tape into the VCR and immediately we were watching some weird B-movie takeoff of The Exorcist.]

SPIN: Miles, I don’t like to watch this kind of stuff. I hate it. [Especially in the presence of Miles’s voice.] It’s too dark.

Davis: You know, Jennifer, you are brilliant, obviously. But you have to be careful, because you’re very open. You get it all—the good and the bad.

SPIN: Are you the receiver?

Davis: Yeah. You know, someone told me, you can go so far, but you better not cross a certain line. Did you know more people die at night?

SPIN: You know once when Richard was on freebase, he saw himself as the embodiment of the Devil, half nude, walk through a wall.

Davis: Freebase…

SPIN: Bad stuff.

Davis: What the fuck do you know about it?

SPIN: For starters, I used it.

Davis: How did you kick?

SPIN: No problem. One day, I came home and found Richard freebasing at the kitchen counter with the new housekeeper. I moved out. I wrote a song, “Your Woman Is Freebase.”

Miles just stared at me, and I wondered why. At this point in the movie we were watching, a priest’s head fell off and worms began crawling out of his neck. I asked Miles to change it, and he put in another tape, this time an old B movie starring Ryan O’Neal. Almost as scary.

SPIN: Miles, I want to ask you a sensitive question.

Davis: What?

SPIN: Do you have AIDS?

Davis: Why are you asking me?

SPIN: Well, it’s a heavy rumor about you—and what if I wanted to sleep with you someday?

Davis: My ex-wife started this rumor. She called up women and told them. [In his book, he says it began when he was in the hospital in Santa Monica with pneumonia.] Would you have left if I said yes?

SPIN: No. You’ve had an extraordinary amount of health problems.

Davis: Yeah, Cicely helped me a lot. My hand was so gnarled up. She got me acupuncture [indicating where the needles were placed], and it straightened out. At first they thought it was honeymoon arm. I couldn’t feel a thing.

SPIN: What’s a honeymoon arm?

Davis: When you lean on your arm in bed, ‘cause you’re having a lot of sex.

SPIN: Sounds as if you had a heart attack.

Davis: That acupuncture fixed me right up. Then I went to La Prairie in Switzerland.

SPIN: For the sleep cure?

Davis: Sleep? The doctor asked me if I sleep. I told him, “No, I only wake up.” I went for those injections. Unborn sheep fetus.

SPIN: They say those are a little dangerous. It’s for rejuvenation, right?

Davis: To build you up. They made me float. I just rose off the bed. The doctor there discovered I was missing a third vertebra in my neck.

SPIN: Maybe it’s from playing the horn. Davis: I never thought of that. I have trouble with sex.

SPIN: What do you mean? Having it? [He nods.] Miles, do you got out much?

Davis: No, but if I put on my medals, all over my chest, no one knows who I am. [He got up, showing me more Maltese medals along with a rather large medal the French bestowed on him, for his international artistic contribution.]

By this point the video was over and we were watching television. Liza Minnelli came on The Arsenio Hall Show in a dated, distressed outfit singing songs from her new album produced by the Pet Shop Boys. I groaned, and Miles seemed agitated suddenly.

“I like her,” Miles said, defensively.

“I don’t,” I said; then, “That song’s a hit in Europe.”

The air was filled with palpable hostility. Clearly I was witnessing a mood swing. Maybe, on some level, Miles felt threatened. I figured I’d better make tracks. I walked over to the window and looked out. It was snowing. It was beautiful. It was Thanksgiving.

SPIN: Have you heard that song of Joan Baez’s [“Speaking of Dreams”]?

Davis: She looked like my mother.

SPIN: “Playing the Gipsy Kings, after the rain and taking tea at the Ritz in / Boots and jeans / … And I am vintage wine, we come from two different worlds / Like every other couple on the Rue de Rivoli.”

Davis: Do you want to spend the night? You can stay here if you want and go where you need to tomorrow.

SPIN: No, thank you. I want to walk my dogs in the snow. Miles, why did you get hostile with me?

Davis: Oh, bitch, don’t pull that “white” shit on me.

SPIN: Excuse me?

Davis: You heard me.

SPIN: [Putting on my coat:] Well, Miles, if it gets really poetic out there, I’ll give you a call.

Davis: Do you need cab fare?

SPIN: I’ve got it.

Davis: Will you call me when you get home?

SPIN: Probably not. [At the door:] Miles, that remark—

Davis: What remark?

SPIN: That I was being “white”—that was out of line, don’t you think?

Davis: [Yelling] Bitch! You are acting “white”!

I marched out the door, letting it slam shut behind me. All the way down the hall I heard Miles playing with the locks. The napkin with his drawing on it was crumpled up in my angry fist. I was also hurt. I also didn’t know what was particularly white about my question; that made as much sense to me as if I had told him he was acting black. I took a long walk in the snow with my dogs and thought of Richard. He could manage to tap into some genetic memory of mine where a hidden residue of collective white guilt lingered. The next few days I read Miles’s book and listened to some early Miles with Charlie Parker—”Koko”—and “Boplicity”; then his later Kind of Blue and Miles Smiles. I listened to the magic without him. No one could take that magic—genius—from him, no matter how nasty the man got. I called him a few days later. I had finished the book.

Davis: You read the whole thing?

SPIN: Yep.

Davis: Are you mad at me? For what I said about white folks? It’s all true, that’s how I see it. I just said it.

SPIN: I guess you saw some bad things, Miles. You were there when the “whites only” signs were all over.

Davis: Yeah, you tell me about my book.

SPIN: Miles, chill. I’m trying to show some respect. [Silence.] It was actually quite sexist, too!

Davis: What are you doing?

SPIN: I was thinking maybe I could see you later and ask you a few more questions.

It was a couple hours later when I arrived at the Essex House. I rang the bell of his suite three times and there was no answer. I figured he was angry or stoned. The next time I tried to contact him, he was in Malibu. I would have loved to ask Miles some more questions, particularly about his prejudice toward white people and his sexism. In his book he says one condition the Knights of Malta have when they make you a member is that you are not prejudiced against any person. There are entire sections of the book where his wrath against white people makes Miles seem like a victim. That’s the last thing I thought he was.

“White people in America get all up in your face because they think they’re God’s gift to the whole fucking world. It’s sickening and pitiful the way they think. How backward, stupid and disrespectful many of them are. They think they can come right up to you and get right into your business, because they’re white and you’re not.”

In his book Miles is angry, honest, impatient, and says what he feels. There is purity in this kind of direct, spontaneous communication—like jazz itself. But within it, there’s some destruction, the same way jazz destroys form. I’d like to ask him about his music, his love life, and his drug addiction. There are wonderful passages in his book about Charlie Parker and Billie Holiday I’d like to ask him about. I wonder if his long bout and continued fight with heroin addiction helped contribute to his anger. Anger can be motivation until it becomes bitterness. I’d like to ask him about that. I’d like to ask him if he has become the beast he was fighting. Then again, maybe I had all the answers I needed.