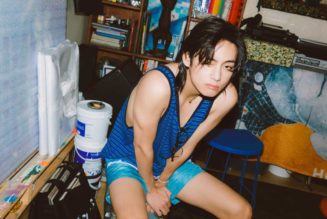

Klaus Mäkelä at Carnegie Hall.

Photo: Fadi Kheir

If conductors were rare earths, Finland would control the global economy. How a country of 5 million manages to keep the world’s podiums supplied with baton-wielding talent is an abiding mystery, particularly since it keeps happening over multiple generations. Klaus Mäkelä sped from student to star so fast that by the time I first heard his name a couple of years ago, I was also informed that he was overrated. It would certainly be hard for him to be rated any higher: Not yet 30, he’s already got his name on the door at the Oslo Philharmonic, the Orchestre de Paris, and the Royal Concertgebouw, where he will assume the top job in 2027.

My only encounter with him, till now, was his impressive New York Philharmonic debut. That was a little over a year ago, and on Saturday, he led the Orchestre de Paris in an electrifying all-Stravinsky program at Carnegie Hall that showed off a conductor with music in his marrow and a warm relationship with the musicians. Mäkelä at 28 reminds me of his fellow Finn Esa-Pekka Salonen at that age: flaxen forelock, blue eyes, high-gloss cheekbones, lithe athleticism, a similar facility with Stravinsky’s jagged rhythms. He even occasionally re-creates the Salonen mannerism of reaching back behind his head with the baton as if he were winding up to hurl a fastball.

But I sense a generational shift, along with a distinct sensibility. Salonen launched his career in the 1980s, when classical musicians were assiduously rerecording the entire canon for CD. In live performances, they worked hard to reproduce the digital clarity and technical perfection of the studio product. The concert became a simulacrum of the recording instead of the other way around. These days, recordings are rarer and often live, and Mäkelä sounds unburdened by his elders’ example. He takes risks, tolerates the occasional messiness as the price of daring, and never lets exactitude get in the way of intensity. That’s not to say the Parisians’ performance was sloppy, only that it sizzled, and if that meant that every staccato passage in the strings wasn’t a perfectly synchronized patter, then so be it.

Mäkelä summoned the earthiness and physical drama of two milestone pieces written for dance, Firebird and The Rite of Spring, the first lushly charming and fantastical, the second crackling and fierce. In Rite, the bass-drum thumps landed like boulders falling from a mountaintop. The lurching rhythms had the vividness of feet thudding on dirt. The orchestra created the illusion of measureless depth so that beneath the main attention-getting tune I heard skittering, moans, rumbles, and the sonic equivalent of a bilious sky. Dissonant brass chords sundered the hall’s warm air like lightning.

The best conductors come to a performance with a clear mental picture of how a piece should sound and the flexibility to allow the moment to speak. It was clear that Mäkelä was listening. When a great walloping chord in the Rite cut off, he stretched out the pause to let the sound stop rolling around the resonant room before moving on. He prioritized silence over the count. I’ve heard conductors impose long pauses for the pure showmanship of the act, halting the onward thrust of music as if they were in control of the Earth’s rotation. Mäkelä made himself fun to watch as well as play for — the way he drew pliant chords out of the winds as if pulling an elastic band, thickened a beat with a jerk of his elbows, or bounced his hands loosely, as if they were riding a cloud of shimmering tremolos. But he didn’t make himself the point; he exerted control without fetishizing it.

He seemed less interested in demonstrating his gifts than in delivering Stravinsky’s sheer sonic extravagance: brash hues, flashes of charm set off by undertones of savagery, an episodic feeling of vertigo. The Firebird stakes out an immense sonic territory, from the basses’ subterranean snores in the opening to great manic explosions of color, and Mäkelä’s vision was ample enough to contain it all. It’s difficult to recapture or even convey the century-old radicalism of Rite of Spring, which our musical culture has so thoroughly absorbed. A common calling card of virtuoso conductors everywhere, it often winds up as gleaming and spotless as a new car — a complex luxury product reproduced with appropriate flair. Mäkelä, though, managed to capture some of the work’s wildness.

The audience reacted with obvious excitement, but I was more struck by a different response. When Mäkelä emerged from the wings for a third curtain call and waved the orchestra to its feet, the musicians refused to stand; they were too busy stamping their feet in appreciation. In any other business, seeing the rank and file applaud the boss would smack of corporate fawning. An orchestra is generally a tough and skeptical creature, so its ovation suggested that, given the right leader, even a jaded bunch of pros can surprise themselves.