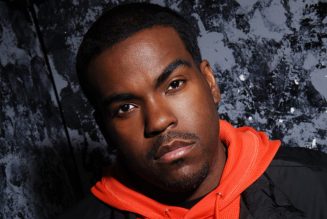

The Sh1.7 billion Kisumu Oil Jetty on May 5, 2023.

As I was writing, a team of top officials from the Ministry of Energy and Petroleum, Kenya Pipeline Company and the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority was in Uganda to discuss Kampala’s recent move to change the route it uses to procure its oil and its intention to decamp from Kenya’s Open Trading System (OTS).

The Ugandans have sent notice that they will be buying their stuff via their recently constituted National Oil Corporation and argued that the Northern Corridor has become expensive for them especially after Kenya introduced the so-called G to G system. They have threatened to shift to the Central Transport Corridor that starts from Dar es Salaam port all the way to Kampala.

Methinks that the decision by Uganda to dump the OTS is not informed by economics per se. In the first place, I doubt that Dar es Salaam has the wherewithal to suddenly ramp up capacity to handle the circa 140,000 cubic metres, which Kampala has to import. Oil handling terminals- and the capacity to store product before it is transported upcountry is clearly going to be a big challenge for Kampala.

Furthermore, the sheer number of trucks that Uganda will need to transport products from Dar es Salaam to Kampala is simply mind-boggling.

Thousands of trucks

Mark you, a typical truck carries only 40 cubic metres. It means that Uganda will need to deploy thousands of trucks on the Central Transport Corridor to move the product to Kampala. There is also the issue of the journey hours for trucks between Dar es Salaam and Kampala compared to the distance between Eldoret and Kampala. The longer journey hours will come with additional costs.

Then you have the argument of economies of scale. With Uganda accounting for a mere 14 percent of the total quantities under the OTS, it means that Kampala’s cargo is not enough to fill capacities of large vessels that the OTS has been using such as the LR 2 that carries up to 100,000 tonnes. And with KPC pumping product in batches, segregating Kampala’s product will be a big challenge.

We can only wait to see how Kampala will deal with these challenges.

But even if Uganda were to decide to switch some of the capacity to the Dar es Salaam port route, it will continue using the Northern Corridor- which will be the most vital economic and transport corridor in the region.

What are we likely to see in the region in future? As countries in the region continue to shadow box and plot to outwit each other over economic dominance and geostrategic significance, what is going to make a difference is the amount and level of investment that a country commits on infrastructure and supply chains that connect it to its neighbours.

Let’s face it, our neighbours are permanently engaged in a cloak-and-dagger game with us over economic dominance.

Three years ago, the Ugandans decided that they will be routing their crude oil pipeline through Tanzania instead of Lamu. This was shortly followed by the announcement by Kigali that it would be developing a railway link through Dar-es-Salaam port, instead of Mombasa.

Kampala reasoned that land compensation costs in Kenya were too high. They also invoked the issue of insecurity on the route to the coast of Kenya. This, is despite Kenya offering to allow them to build their crude pipeline along Kenya Pipeline Company’s wayleave. The argument about security does not hold water because KPC has been operating an oil pipeline on this route for over 30 years without any major security breaches.

The point here is this: in the context of the battle for economic dominance with our neighbours. We must fight to make sure that we dominate everybody in building roads on the major transport corridors, seaports, waterway links and networks of inland container terminals

Just the other day we were dismissing Nairobi- Naivasha railway as a railway to nowhere and dismissing the Naivasha inland container terminal as ill-conceived. Today, we are surprised to see that the volume of traffic consigned to the facility is growing and that literally all neighbouring countries are lining up to be accommodated there.

The only reason we struggled to get a good economic justification for the Kisumu jetty project short- termist thinking. The Kisumu project must be seen — first and foremost, as an ambition by Kenya to secure and improve hinterland accessibility to the port of Mombasa. With volumes beginning to pick up and with the price comparisons between transporting petroleum by road and using lake vessels I have seen- that facility has the potential as one of our key and strategic investments along the Northern Corridor.

The writer is a former managing editor of The East African