This evening, Vice President Kamala Harris is announcing that the United States will no longer conduct anti-satellite, or ASAT, missile tests — the practice of using ground-based missiles to destroy satellites in orbit around Earth. Harris is challenging other countries to make the same commitment and establish this policy as a new “norm of responsible behavior in space.”

Harris will speak more extensively on the new commitment during a speech at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California this evening. Harris currently serves as the chair of the White House’s National Space Council, an executive advisory group that helps to set the nation’s space agenda.

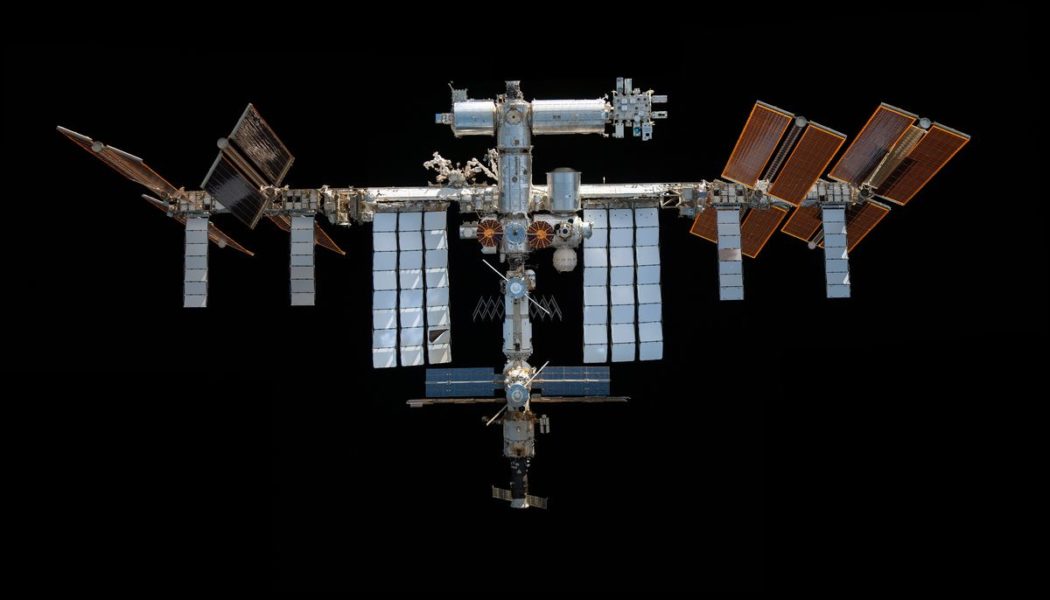

This declaration comes five months after Russia conducted an ASAT test in November. The country launched one of its Nudol missiles from Earth, which destroyed Russia’s Cosmos-1408 satellite, a Soviet-era spacecraft that’s been in orbit since the 1980s. The event created a massive cloud of more than 1,500 pieces of trackable debris as well as thousands of smaller pieces that couldn’t be detected. The satellite’s destruction occurred in a fairly close orbit to that of the International Space Station, prompting the astronauts on board to temporarily shelter inside their spacecraft in case the debris damaged the facility.

The United States swiftly condemned the test, as did NATO and the European Union. Tests like these — known as direct ascent ASAT tests — are widely reviled because of their propensity to create dangerous debris. The leftover pieces from ASAT tests can spread for miles and often stay in orbit for months and even years, menacing the space environment. ASAT debris can’t be controlled and moves at many thousands of miles per hour, so even a small fragment can damage or take out a functioning satellite during a collision.

Though the space community generally despises ASAT tests, no country has called for a moratorium on the practice in the more than 60 years that countries have tested the technology. Now, the United States is taking that step in light of Russia’s actions. “I think it’s a really powerful move,” Victoria Samson, an expert on military space at the Secure World Foundation think tank, tells The Verge. “The US is the first country to make this sort of declaration, and I’m very much hoping other countries will follow suit — particularly those who have also tested anti-satellite weapons in space, but even those who haven’t.”

Since the same missile technology used to destroy a fast-moving satellite can also be used to intercept intercontinental ballistic missiles, ASAT tests can act as technology demonstrations. But these tests are predominately very loud shows of strength. When a country demonstrates that it can destroy one of its own satellites, it’s broadcasting to the world that it has the capability to destroy an adversary’s satellites, too.

So far, no country has actually used ASAT technology to take out another country’s spacecraft. Instead, only four countries have demonstrated this technology on their own satellites. Russia’s been testing its Nudol technology for years now but only successfully destroyed a satellite from the ground in November. In 2019, India destroyed one of its own satellites, creating a few hundred pieces of debris — half of which have already burned up in our planet’s atmosphere. And in 2007, China destroyed its defunct Fengyun-1C weather satellite, creating thousands of fragments. Some of that debris is still in orbit today and causing problems; in November, just before Russia conducted its ASAT test, the International Space Station had to boost its orbit to get out of the way of one of the leftover pieces of China’s ASAT test.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23398380/51750549427_63b21c49b5_o__2_.jpg)

The US has perhaps been testing ASAT technology the longest and conducted its last debris-generating test back in 2008. As part of a mission called “Burnt Frost,” US Strategic Command launched a missile at a decaying spy satellite from the National Reconnaissance Office. The US made the excuse that the satellite contained nearly 1,000 pounds of a toxic propellant called hydrazine and shooting down the satellite was simply a safety measure to prevent the propellant from doing harm if the satellite survived the plunge through Earth’s atmosphere.

Though it’s been more than a decade since the US has conducted an ASAT test, the US has been reluctant to call for an end to the practice. “Up until a couple of years ago, that was not the US position,” Samson says. “The US wanted complete freedom of action in space no matter what.”

The orbit around Earth has grown increasingly more crowded over the last few years, though. It has become easier and cheaper for companies to launch privately built satellites into space. Meanwhile, companies like SpaceX and OneWeb have begun building out mega-constellations of satellites in orbit, consisting of hundreds and even thousands of satellites. Earth’s orbit is only going to become more congested, as other companies and countries consider launching similar mega-constellations to stay competitive.

Adding even more debris to this environment will just increase the risk of collisions. Russia’s ASAT test in November demonstrated just how threatening that debris cloud can be when it put the astronauts on board the International Space Station in danger. In December, Kathleen Hicks, the US Department of Defense deputy secretary, expressed a desire for the international community to halt ASAT tests during a meeting of the National Space Council. “We would like to see all nations agree to refrain from anti-satellite weapons testing that creates debris,” she said.

Now, the Biden administration is making that wish official with the US leading the way on the effort and calling for other countries to do the same. However, it’s unclear which countries will actually follow suit, and there is currently no way to hold countries accountable for their pledges.

However, the international community does seem poised to take a stand on ASAT testing in some capacity. In May, the United Nations is convening an open-ended working group tasked with establishing “norms, rules, and principles of responsible behaviors” in space. One of the topics the group is concerned with is debris-generating events caused by the intentional destruction of spacecraft in orbit. “From what we’ve heard, a lot of countries are interested in something like an ASAT test moratorium,” says Samson “So I actually think this does have the possibility to get a groundswell movement towards international support.”

Of course, there’s a lengthy process between today’s announcement and some kind of declaration of international law. “This is absolutely a first step,” says Samson. “We’re hoping that there will be plenty more.”