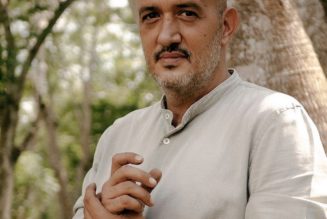

This week on The Trip podcast: Journalist Jorge Nieto on covering Tijuana’s good and bad days, losing friends to violence, and what happens when you accidentally get the wrong beer for members of the Sinaloa cartel.

Ah, the sound of a dozen hellhounds slavering for a taste of sweet gringo flesh. This is actually part of my perennial Mexico soundtrack, from the south or north, whenever the omnipresent guard dogs catch that scent of vanilla or sulphur or whatever the hell Caucasian men smell like when they’re wandering around looking for an address they cannot find.

This particular bit of the Baskervilles was on the Otay Mesa, a plateau that spans the border from Tijuana to San Diego. There’s an absurdly wide view looking down across the sprawl of Tijuana from up here. And people like the neighborhood because there’s a border crossing so close you can ride your bike into the states with ease, or at least you could before 9/11 and the drug wars and the end of the legend of partytown Tijuana. This is the neighborhood of journalist Jorge Nieto, a man with a literal and figurative expansive view of this city and its many lives. After I finally found the right address, we drank mightily from his bottle of mezcal, talked about the good old days of TJ, losing friends to violence, and about what happens when you accidentally get the wrong beer for members of the Sinaloa cartel.

Here is an edited and condensed transcript from my conversation with Jorge. Subscribers can listen to the full episode here. If you’re not on Luminary yet, subscribe and listen (and get a 1-month free trial) by signing up here.

Nathan Thornburgh: Well, we have a drink.

Jorge Nieto: Yeah, we have a nice drink here. Mezcal.

Thornburgh: A nice, simple mezcal from Oaxaca.

Thornburgh: Cheers.

Nieto: Cheers. Salud.

Thornburgh: Did you do a lot of traveling when you were growing up here? Did you go see other parts of Baja, other parts of Mexico?

Nieto: Yes. Well, mainly Baja. I’m originally from Guanajuato. I arrived in Tijuana when I was four years old, with my parents. I spent my teenage years in Ensenada, discovering life, friends, girlfriends, alcohol, drugs, parties. And I started to work as a waiter at Papas and Beer.

Thornburgh: Papas and Beer. That’s kind of an institution. Right?

Nieto: Yes, it’s one of the more famous nightclubs in Ensenada. I was under 18. They opened a restaurant, where I worked. It attracted a lot of tourists from the cruise ships–on Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. So, for me, working those days and early mornings was the best, because I got a lot of tips from these tourists who would come off the cruise ships and into the local stores, bars, and restaurants—to get drunk.

Thornburgh: At nine in the morning.

Nieto: Yes, at nine in the morning.

Thornburgh: So that was just a part-time job?

Nieto: Yes. I was finishing high school, and when I finished, I didn’t know what I wanted to do next so I decided to move to Tijuana just to explore.

Thornburgh: So you took that cruise ship money to come and have a good time in Tijuana and live and be independent?

Nieto: Yeah, basically. To have a good time. That was in 1999, 2000, the last of Tijuana’s party years. The legend of Tijuana from the ’90s was almost over. So I got in one or two years of good parties. I remember the Safari Club, which had college nights on Wednesdays, and they didn’t allow Mexicans inside—just the people from Southern California who came to party. But we always knew the right people, so we managed to get in, and we went to these crazy parties.

Thornburgh: It’s a little fucked up, though. Obviously, the policy is super fucked up, but just even going in and saying, “All right, we crashed this party, but we had to crash it because they didn’t actually want us in here.”

Nieto: You’re right. The policy sucks. There is no way to justify it. But Tijuana used to be like that because they got so many tourists from Southern California. And then the crises hit. First 9/11, then the violence which started around 2006.

After 9/11, the time it took to cross the border went from 30 minutes to three hours.

Thornburgh: Here in Tijuana, where the cartels were fighting.

Nieto: They were fighting in the streets, downtown, in the Zona Rio, and in the city’s squares. So, Tijuana lost the tourists. Clubs closed, the Safari Club went out of the business. Because they depended so much on tourists from California.

Thornburgh: If they weren’t getting the mainline injection of co-eds from La Jolla, they could not stay in business.

Nieto: Exactly. And after 9/11, the time it took to cross the border went from 30 minutes to three hours. That was the first strike. The second strike was in 2006, when Mexico’s former president, Felipe Calderón, started the Guerra contra el Narco—the war against the narco—in Tijuana and Michoacán. Calderón sent hundreds and hundreds of military troops to fight the Tijuana cartel, mainly. I think the president attacked the Cartel del Golfo and the Cartel de Tijuana, and allowed the Cartel de Sinaloa to rise. And then the Cartel de Sinaloa, in the six years of Felipe Calderón and then the next six years of President Enrique Peña Nieto, just got stronger.

Thornburgh: I hear about that a lot. It sounds like a conspiracy theory, and yet it also really checks out.

Nieto: It does. But this is my perspective, and it’s because I was living here and I knew the Tijuana cartel, how they worked, and how they powerful used to be.

Thornburgh: Right.

Nieto: So it was quite strange in the national context.

Thornburgh: In the national context, the army comes in, starts suppressing some cartels, leaving room for another. And the violence here got unmanageable, and very surprising. Tijuana was, at some point, was one of the deadliest cities on earth. What’s that like—when your city spirals into this alarming violence? What does that feel like?

Nieto: Well, at that time, around 2003, I was working at a TV station in Tijuana. They sent me to the report on the streets. When Felipe Calderón started with the Operativo Tijuana, I was working for the cultural section with a reporter. I was the editor and the cameraman. We used to cover concerts, theaters, exhibitions, openings, etc., and so we started to do stories related to the violence from a cultural perspective. We were worried. We were thinking about the impact of the [narco] music on kids, at that time, for example, the narcocorridos [cartel ballads] and the narcocultura.

Thornburgh: Those kind of stories are the best way to talk about violence. You can just say there were five wounded and one killed, but this way, it’s more about what’s happening to everybody else. Can people go out anymore? How does the culture change? Are they doing parties at home now? All of those things, I think, that’s fascinating. That’s where people can also start to identify with what life is like in a conflict zone like that.

Everybody in Tijuana has lost a friend, and everybody knows someone inside the criminal structures

Nieto: Definitely. We started to get to know people from civil society organizations who were thinking in a similar way, trying to do something else, not just to respond to the violence with guns and the military and the police. They were doing theater workshops, cinema, movies at the park, that kind of thing. So we started to cover the violence from this angle.

Thornburgh: This was your territory and you were using that as a lens to talk about the cartel violence. And these were big changes. It was a big moment in the history of this city, and you got to be there on the frontline of telling some of those stories. Did you feel personal fear for yourself or your friends?

Nieto: Everybody in Tijuana has lost a friend and everybody knows someone inside the criminal structures. And a lot of people have a relative or loved ones in jail. I lost two friends.

But when the city lost the tourists, the gastronomy industry started to do something different. They started to think about the local market, and started to created more local concepts. It was the restaurants that started this movement, and now Tijuana is famous for its food, wine, and craft beer. I was interested in that. I thought, “Oh, okay. They are doing something and trying to attract new customers.” And now Mexicans were allowed to get into the bars.

Thornburgh: Finally.

Nieto: Finally.

Thornburgh: That would be amazing—if they just had a super fucking empty restaurant and said, “No, sorry. No Mexicans. I don’t know when Debbie’s going to show up. Debbie hasn’t been here in a few years, but we’re holding the table for her and her sorority sisters.”

So in that period, you started to notice the restaurants. And this was part of the reporting that you were doing was still in the cultural area. How did that evolve after 2006, 2007 and 2008? Where did you end up going from there?

Nieto: I kept working for that TV station for a while, but [eventually] I quit my job and went freelance.

Thornburgh: Why did quit the formal job?

Nieto: Because I was getting a lot of work with this agency in L.A., covering the violence and the migrant issue. They were asking me for a lot of stories, but I was also starting to get inquiries from other journalists and other TV stations. Some of these inquiries were for fixing, and I couldn’t take these assignments because I was working in an office and I had to be there from Monday to Friday. I thought I was missing an opportunity, and the experience, of working with someone else from another country who has a different perspective. So I decided to quit this job and jump into freelance work.

I was a little afraid to take the decision. I didn’t know if I was going to get enough work, but I did start to work more as a fixer. Journalists started coming to Tijuana, for the migrant stories, mainly. A lot of journalists used came cover some stories related to violence and the migrants. And it was my field. I know that field. I know all the shelters of the city. I know the directors of the shelters. I know how to approach to the migrants, and I know dealers, I know human traffickers, I know some pimps, I know some prostitutes.

Thornburgh: Yeah. And how did you gain that knowledge? How did you build your Rolodex over the years?

Nieto: Well, over the years, just hanging out in bars, and as a reporter spending time in neighborhoods. Getting outside of offices—the governor’s office, the mayor’s office. I never looked for that kind of coverage when I was at the TV station. I was looking to go to parks and into the streets to report stories. So, I started to know people.

Thornburgh: You knew that your depth of knowledge of the pimps of Tijuana would come in handy one day, and you wanted to build that contact list up.

Nieto: Yes.

Thornburgh: It’s completely vital. You need to know everybody, because you never quite anticipate the requests that’ll come in. Maybe it comes in from a foreign journalist who wants to use you as a fixer, maybe it comes in from your own journalism, maybe there’s some violence in the sex worker industry and you need to know people on all sides of that industry. That’s classic journalism. That’s 101, to be able to have those connections there.

Nieto: Exactly. And sometimes, I drink a beer with them as well.