Last night, a friend alerted me to a filmed concert on the Isle of Wight in 1970 where Joni Mitchell performed. She said it was on YouTube. It was one of those post-Woodstock ridiculous assemblies of thousands of people who seem to be walking around, talking, getting high, eating, and every once in a while, listening to the music. Onto the stage walks Joni Mitchell and sadly tries to sing her quiet little song “A Song About the Midway” from her second album, Clouds, to this sea of people in an advanced state of distraction, and suddenly my weeks of working on this piece about her seems overblown and out of proportion. Maybe I am not, in all of this, writing about Joni Mitchell? Maybe I am writing about me and my reactions to things as I change and they change; the times, and me. I don’t think I would have gone so crazy for her now…but this was then, and I did, and it seems worth recounting.

I had to turn it off in the middle of the first song, something I NEVER would have done when she was on her pedestal and I worshipped her. I didn’t even like the way she was changing her own vocal lines like Patti LaBelle and unsimplifying the tune which seemed to crumble under the weight of such sudden importance, but I thought, this may have been her nerves, her insecurity at confronting what seemed like a million people, with her little guitar, her yellow hippie dress, no make up, and her purity.

<!– // Brid Player Singles.

var _bp = _bp||[]; _bp.push({ “div”: “Brid_10143537”, “obj”: {“id”:”25115″,”width”:”480″,”height”:”270″,”playlist”:”10315″,”inviewBottomOffset”:”105px”} }); –>

When I look at what I have written here, I think, no wonder she got louder, she had to sing to more and more people.

On April 20th, 1969, in The New York Times, there was an article about a then, not very well-known singer-songwriter named Joni Mitchell.

“Her music has a haunting, unearthly quality produced by the strangeness of the imagery in her lyrics, the unexpected shifts in her voice, and the unusual guitar tunings she uses. She is one of the most original and profoundly talented of all the contemporary composer-performers—- who have evolved folk music into art-rock.”

It was written by my sister Susan Lydon.

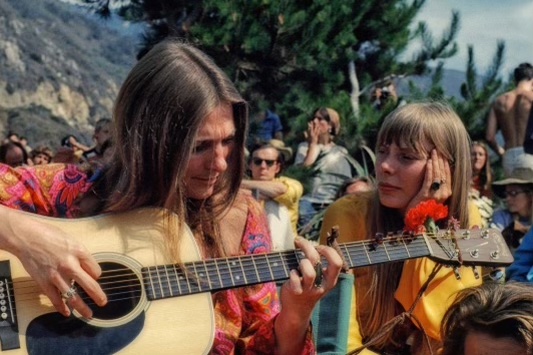

There was a photo of Joni Mitchell walking among the trees with her friend Judy Collins. Judy was quite well known at the time and had put Joni on the map by recording her song “Both Sides Now,” and making it a hit. I was not yet 13. Though my mother had a short but stratospheric career as a singer and comedian in the Borscht Belt before I was born, and my two older sisters, Susan and Lorraine, played the guitar and sang all the great folk songs of the day in our living room often, to our great enjoyment, and Sheila, the youngest of the sisters, played the piano, because I showed signs of what they considered to be an extraordinary ear, and because I was the only boy in a Jewish family where sexism is written into the hierarchy, music was ceded to me. Susan told me I needed to hear this woman’s music because I would love it. I worshipped my older sister and thought she was the most brilliant human being on earth, so I registered what she said and asterisked it inside myself as very important. Little did I know that when that information was taken out of my inner filing cabinet, my life would be forever changed.

Conveniently, 1969 was also the year the movie Alice’s Restaurant, was released. It was based on Arlo Guthrie’s song of the same name and it starred him as well. My niece Maggie was only four at the time, too young for almost anything that happened in that movie, but my sister Lorraine took us to see it anyway. This was during one of the many times my mother sent me to the city to cheer Lorraine up.

By now, her marriage to Bobby Shapiro had ended, and she was living with her friend Danya on the Lower East Side, self-destructively experimenting with heroin, and in, what seemed like, a free fall into depression. I remember very little about the movie except for this, at one point, a hippie on a motorcycle, a speed freak, is reeling down the highway, has a terrible accident and dies instantly. It is very sad and there is a funeral in what appears to be a clearing in the woods. At one point, a blonde woman with flowers in her hair appears with a guitar and sings a song which, I knew immediately, had to be a Joni Mitchell song. It had the strangest most exotic harmonies, nothing like I had ever heard in folk or pop music. They were spiced up chords, neither major or minor, almost modal, and they were unpredictable in where they led.

For me, this was what was often disappointing in folk music, though I couldn’t have put it into words at the time. I always knew what the music was about to do, and even if the words were complex, expressing rich ideas including paradoxes and ambivalences, the music did not. The music rarely took the journey the words took, and always seemed less skillfully rendered than the words. This song shocked me, and stayed with me, haunting me for the rest of the movie. I couldn’t think of anything else. When the credits rolled at the end of the movie, sure enough, I was right. It was a song called “Songs to Aging Children Come” and it was indeed by Joni Mitchell, though that was not Joni Mitchell singing in the movie.

Joni and my sister Susan were born in the same month and year, my sister told me, so they were both, at this point, 25 years old. I asked for the album it was from, Clouds, and became transfixed, mesmerized, completely and overwhelmingly obsessed with Joni Mitchell. At that point, all that was available were her first two albums, Song To A Seagull, and Clouds. Song to a Seagull was a quieter album, the sorrow was gentle, genial, it felt like having your tarot cards read over a cup of tea, but Clouds had a darker feeling to it, a failed marriage, a protest song…both albums were iridescent, like the underside of a butterfly wing, or the inside of an abalone shell.

Susan gave me her address in California, on Lookout Mountain Rd., in Laurel Canyon. I started writing to her and sending her presents. I would draw her pictures to accompany my impassioned letters of adoration. I would even decorate the envelopes. One day, I was shopping on St. Mark’s Pl. in the East Village in New York where I bought myself two pairs of corduroy landlubber bell bottoms. One pair was sort of mauve or dusty rose and the other, purple. No matter how many times people called me a fag, I couldn’t resist color and always bought clothes that exacerbated the situation. At one of these stores, I found a record that was made for Scorpios…it was an astrology reading. I sent it to Joni in her next gift package. I received a letter postmarked December 11th, 1970. It was in a small nondescript envelope but I recognized the cheery handwriting. I almost had a heart attack. The letter was written on paper clearly hastily ripped out of a notepad so its edges were frayed.

Hello Ricky,

Thank you for all your letters and thoughtful things. I love things you make yourself. I haven’t played the record yet because thieves ripped off my record player. I’m on my way to San Francisco to sing on a friends record and to get out of the L.A. air.

Goodbye,

Joni Mitchell

I loved the language…“thieves ripped off my record player” and the way her handwriting in a bright blue sharpie seemed to almost spill off the page like it was about to jump in the water. When viewed now, the handwriting is recognizable as she has published so many paintings and lyrics and drawings with her signature on them. The huge “J” after which, all the letters get smaller. Oh, it was so glorious to receive this note. The record on which she was on her way to sing, was Carol King’s Tapestry. Her relationship with Graham Nash, about which, much of my sister’s article was about, had ended, and now she was seeing James Taylor. Together, they were doing backups for “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?”

It is hard to describe what caught me about Joni Mitchell’s work, but I want to try. First of all, when I was in Seventh Grade, Mr. Gary, the gay music teacher, allowed me to teach my own class on Joni Mitchell, though I included two Donovan songs, “Isle of Islay” and “The Magpie,” as well as the Cat Stevens song “Into White,” which I felt entered the exalted place where I felt Joni’s work belonged, and therefore, my thesis. When I did my research on Joni, in preparation for the class, I learned that Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, where she grew up, was noted for a kind of Canadian yodeling. That seemed to explain her ease with registers, how she could go from singing in her chest to soaring in her head voice instantly, and so fluidly, like a yodel; think “Oh Ca-na-da” in “A Case Of You” or “CaliFORnia, I’m coming home” in “California,” or “I was walking along the ROAD” in “Woodstock.”

By this point, I was as in love with poetry as I was with music, and in particular, the confessional poetry of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton. Joni Mitchell, Donovan and Cat Stevens in the songs I mentioned seemed to have settled on a kind of contemporary art song…their lyrics seemed like poems, and in Joni’s case, often, confessional ones, and the music circled the words in a perfect enmeshment of mood and tone, as unpredictable as the lyrics. If I were to mention songs I was obsessed with — though I could name every one — on Song to a Seagull, it would be “Marcie,” which to this day, tears my heart out whenever she sings “To the sea,” holding “sea” through what seems like at least five changes of landscape, and playing with the words “red” and “green” in the most imaginative way, allowing them to represent over time, the colors and flavors of candy, the changing seasons, and the stop and go of traffic lights.

On Clouds, it would be “Songs To Aging Children Come,” and “I Don’t Know Where I Stand,” though even as I write those titles down, “The Gallery,” drifts into my head, admonishing me for leaving it out. But those two stuck out to me as the most strangely unique and beautiful. When I was a boy, my sister Susan would read Edna St. Vincent Millay poems to me, lulling me into sleep, like lullaby. I knew “Ballad of the Harp Weaver,” so well, it seemed to be my story; the poor sad little boy who awakens to a pile of golden clothing while his mother is frozen dead at the harp she wove them on.

Joni’s lyrics were like Millay’s poems, formal and deep, but also, playful, wry and funny, woven from golden threads. She never repeated anything randomly, she told stories and her lyrics evolved in the course of a song. She was original and thoughtful. Listen: “Through the windless wells of wonder, by the throbbing light machine, in the tea leaf trance or under, orders from the king and queen;” or “Crickets call, courting their ladies in star dappled green. Thickets tall, until the morning comes up like a dream;”

I mean, who wrote lyrics like that? I just simply had never heard songs like that. And it was all just a woman and her guitar. They were so simply done and so hair-raisingly intimate. She was singing to me! But then, with her next album, Ladies of the Canyon, she exploded out of herself. She brought in a new instrument, the piano, and an occasional obligato instrument, like the clarinet in “For Free,” and in songs like that one, “Woodstock,” “Willy,” and “Blue Boy,” she seemed, for me, to enter a place no previous songwriter had ever entered. She carved a world of sonorities and words that were wholly contemporary but rooted in historical tradition, complex enough to be a part of the classical musical canon. This was not just the work of a troubadour whose music was simply a vehicle for the words, no, she was a true poet and a true composer. It is interesting that she began as a painter, because she certainly knew how to paint with notes and words. She was a real musician. Just listen to the first four bars of “Ladies of the Canyon.” Where have you ever heard guitar chords like that before? I first heard a song from Ladies of the Canyon on the radio but the album wasn’t out yet. It was “Willy.” “Willy is my child, he is my father. I would be his lady all my life.” There is something about the radiance and unfulfillment of it that feels straight out of Willa Cather’s “My Antonia,” when Jim tells Antonia she is everything to him a woman can be for a man, a sister, a mother, a lover, but we know it will never work.

“Willy,” conveyed so many emotions at once. I went mad. I called all the radio stations and badgered my sister to see if anyone could get me an advance copy. I thought of pestering Joni! But I had to wait like everyone else. I taught myself to play the song from what I remembered in one hearing. In some ways, that is my favorite of her albums, because it is where, for me, she catapulted herself into a whole new language she was already on her way to.

But then, Blue. What to say about Blue.

Now she introduces a new instrument, the dulcimer, but not the way anyone else plays it, she reinvents it. From the very first notes of “All I Want,” the first song on the album, you are thinking, ‘What is that sound? Is it an autoharp? What are those chords? What is that instrument?’ And in one song after another there is unbearable joy, unendurable sadness, and the baldest candor anyone could imagine… “Oh, you are in my blood like holy wine, you taste so bitter and so sweet, Oh I could drink a case of you, darling, and I would still be on my feet, Oh I would still be on my feet.” With songs like “All I Want,” A Case of You,” “Carey,” “River,” and “California,” to name a few, she has created her own genre, her own universe. For me she was now as much a genius as Benjamin Britten, Kurt Weill, Alban Berg, Samuel Barber, and all the other composers I idolized at the time, and just as much a poet as my beloved Millay. I didn’t distinguish between “serious,” or “classical,” “pop” or “commercial.” I just loved what I loved ardently, and that was that. I wanted to know her, I loved her with all my heart as tenderly as if she were my closest friend or my sister or my girlfriend. I dreamed about her.

I thought about her day and night and I couldn’t shut up about her. I drove everyone in my life crazy with my Joni Mitchell mania. She was going to make her Carnegie Hall debut in February of 1972. I was 16. I wanted to do something big, a grand gesture to top myself, exceed everything I had done for her already. I had taught myself to embroider and I got really good at it. I was intoxicated with the huge palate of colors you could find in the shimmering silky threads. I became a habitue of the craft shops and dreamed up patterns and designs. I would draw scenes and figures, flowers and butterflies on to fabric and fill them in with all the stitches I had learned…Backstitch, Split Stitch, Satin Stitch, French Knots, Chain Stitch, the Lazy Daisy Stitch, and I decided I wanted to make Joni Mitchell a dress!

I enlisted my friend Denise to help me. Someone had to make the dress, and she was more than happy to be part of the “make Joni Mitchell a dress” campaign.

I got Joni’s measurements from my sister Susan who said Joni was the same size as her, and if I made something that fit her, it would fit Joni. With Denise’s help, I bought several yards of a soft chocolate brown muslin. I am not sure I would have chosen that color now, but so be it, it seemed right at the time. Denise found a pattern for a sort of caftan with a drooping neckline and sleeves that belled out…something that would be comfortable and easy to throw on, very hippie chick and flower power. She made the dress, and we fit it on my sister. It was perfect. I started embroidering it. I embroidered all around the hem, up and down the collar line, around the sleeve ends, and here and there throughout the bodice of the dress. I embroidered birds, autumn leaves, wildflowers, bumblebees, and sunsets. When I was done, it was beautiful, at least to my eyes it was. Excitedly, I wrapped it in brown paper so I could paint on the package, and I painted, what felt like I was painting, a portrait of Joni. On the day the tickets were supposed to go on sale, I got up at three in the morning to get a train from Island Park, the town where we lived, in Long Island, into the city. I was determined to be the first person in line. The journey took a little over an hour. It was a freezing cold January morning. I was at Carnegie Hall by 4:45 and indeed I was first in line.

The second person was my new friend from ninth grade at West Hempstead High School, Jodie Siegel, a fellow Joni aficionado, though an amateur compared to me. No one could rival my devotion. They didn’t even try. Practically everyone knew what I had planned, so friends and acquaintances from school started arriving intermittently to wait in line as well, to be part of the big happening, until finally, the box office opened at 10. Excitedly, trembling and half-frozen, I walked up to the ticket booth. I could barely get the words out. “Front row center seat, please,” I said. I had never been first in line, in this privileged position of being able to ask for exactly what I wanted. There was a delicious power to it. The lady in the booth smiled like she knew my type; the crazy wide-eyed first-in-line fan who would do anything for their adored idol. She went straight for the ticket, pulling it out from the rubber-banded VIP bundle, with a smile of satisfaction knowing how happy she was making me. My mother, who clearly, had never on her own bought a ticket for a concert or a show in New York City, had given me a check from our bank, The National Bank of North America, and I handed the check to the ticket seller. She looked at it and then looked at me…“We don’t take checks,” she said. “What?” I said, “We don’t take checks honey. Cash only.” I panicked, “But that’s all my mother gave me! I don’t have anything else.” “I’m sorry,” she said,” we don’t take checks. You’ll have to go get cash and come back.” “Can you save the seat for me until I get back?” I asked. “No. I’m sorry.” She said, “We’re not allowed to do that.” She pitied me, but she was granite-hard, unyielding. I cried, railed, and bargained but to no avail. She would not take the check or save the seat, and by now, my insistence and hysteria were wreaking havoc in the line.

Jodie had cash, but only enough to buy her own ticket, and I even imagined I saw a faint gloat on her face that she was in fact going to have a better seat than me at the Joni Mitchell concert. I suddenly wanted to kill her. I had that feeling where you are so upset you can no longer swallow, and my head was exploding. Abject and miserable, I bolted from the line. I had to run around 57th St. wildly and insanely looking for a National Bank of North America, which, believe me, was not as omnipresent as today’s Chase or Citibank. When I finally found one, I had to beg them to call my mother and our branch in Island Park to vouch for the amount so they could give me cash. However long this took, which felt like an eternity, by the time I got back to Carnegie Hall, it was early afternoon, and there was now a line around the block, and I had to get on the end of it. Everyone I knew had already gotten their tickets and they were gone so there was no one there to substantiate my position should I try to go to the front of the line. I was heartbroken, shattered and lost. I wept, bit my nails and ground my teeth feverishly until finally, I got up to the ticket booth again. The same gravel-faced gargoyle who seemed hell-bent on ruining my life stared out at me with nothing but contempt and antipathy. I wish I could say, she kindly put the front row center seat aside for me and was waiting for me to come back, but instead, she almost seemed to relish my misfortune. I secured a ticket, though not in the front row, but in the center section somewhere towards the back of the hall. I never scolded my mother, or even held it against her…but the wound was deep, and when I think of it now, I could murder her, but she is dead. Up until that moment, I had never been so crestfallen in my entire life.

However, all was not lost. Jodie Siegel got the center seat in the front row, next to Neil Young. The night of the concert, I had dinner with my three sisters before the show somewhere in the vicinity of the hall, though of course, I could barely eat. My stomach was in knots from the excitement. When we got there and found our seats, I knew I could not sit where we were. It was just simply too far away. I marched up to the front of the auditorium with my package under my arm, begged Jodie to move over, which she did happily, knowing something good was going to happen that night, and we squeezed into one of those tiny Carnegie Hall seats together. Of course, I was astounded to see Neil Young next to us, but it was Joni who I was there to worship. Joni.

The lights went down and the concert began. I had never had an experience like this before. I had never loved so deeply a living musician, a living performer, and the experience of her being so close to me, about ten feet away, was overwhelming. There she was in all her radiance, her implausibly high cheekbones, her endearing overbite, her hair the color of wheat reflecting the gold of the spotlights, her crystal-like vulnerability, her little giggle, and that voice, even more soaring in person, filling the hall. She opened with “This Flight Tonight,” from Blue, which is not one of my favorite songs on that record though I understand it now as a good opening number after seeing her at Isle of Wight trying to open with “The Song About the Midway,” which was NOT a good opening number. Then she sang a brand new song, “Electricity,” from the record that would become For the Roses, and I don’t know what I thought that night but it is not one of my favorite songs either, though now I see, it does not matter what she sang that night as I was in such a lather, she could have sung “Mary Had A Little Lamb,” and I would have wept through every song, screaming wildly at its final cadence.

I was not of sound mind. Finally, after about an hour of this kind of ecstatic worshipping at the altar, there was a moment, a lull, when it felt appropriate to approach the stage. She had stopped talking and singing for a second, put down her guitar, and was sitting, with the dulcimer in her lap. While she tuned it, after quieting the crowd which was only calling out and requesting the titles of old songs she said she couldn’t even remember how to play, clearly annoying her, (at one point, she admonished them by saying, “Hey. Do you think anyone ever asked Van Gogh to paint another “Starry Starry Night?”) and before she started the patter into the song “California,” the first song on Side B of her magnificent new album, Blue, about the red rogue on the Grecian Isle, I went up to the stage and whispered meekly, but loud enough for at least everyone I knew to hear, “Joni. I’m Ricky.”

Thinking about it now, I can’t believe I thought she’d remember me, but unbelievably, she looked up and replied through the microphone, with the dearest and kindest familiarity, “Ricky Gordon, my old pen pal!” I nearly collapsed. Everyone who knew me in the hall screamed. I was shaking from head to toe as if I were at the pearly gates come face to face with Jesus Christ. I said, “I made you something,” and I shoved my package across the floor towards her. She looked at it, the pretty painting on the brown paper, the elaborate wrapping, and said, just as she had said in her letter, “I love things you make yourself.” “It’s a dress, Joni! Wait till you see it!” I murmured excitedly, and satisfied, and beaming, I sat back down with Jodie, who clutched me tightly to her as I gloated, and of course, Neil. I buzzed for the rest of the concert like a happy little bumblebee. I wish I could say she opened the package, looked at the dress, oohed and ahhhed, and showed it to the audience. I wish I could say she tried it on so all of Carnegie Hall could marvel at my exquisite handiwork. It wasn’t that dissimilar from what she was wearing, so it could easily have been her Act two dress! Wouldn’t THAT have been a coup?! But she just continued telling her story and sang “Carey,” which was funny and wonderful, but sadly, I never heard from her again.

The next day, in high school, the news had spread about Joni Mitchell talking to me from the stage of Carnegie Hall, and everyone was deferential, like I was a movie star. For one day only, I was a huge celebrity. I have no idea if she ever saw the dress, tried it on, or anything. The truth is, that night was sort of the grand finale to my Joni Mitchell story. First, I was somewhat heartbroken and horrified at not hearing from her, but also, I had exhausted my idolatry, and with each new album, I identified less with her work. The next album was For The Roses, which she wrote in a self-imposed exile from the world, feeling wrung out, hurt by celebrity, its fickleness, its ups and downs, and in need of unbroken space and time. I liked that album very much, and I recognized some of the songs because she premiered them that night at Carnegie Hall, but something was missing, she had become somewhat opaque to me. I no longer found myself memorizing the lyrics, or essentially, even always knowing what the songs were about. I couldn’t even tell you now the order of songs, other than that “Banquet” started Side A and “See You Sometime,” Side B. The title song specifically about the pain of stardom, which I didn’t yet understand, I mean, how could being a star be painful? It sure looked fun to me!

I left high school early. Early on, in ninth grade, I was at the helm of a sort of revolution wherein we started a free school under the auspices of the legitimate high school for students who felt hamstrung or incapacitated by standard educational procedures. I painted a huge black and white mural of what looked like the face of the disenfranchised, in a classroom deep in the margins of this quarter of a mile long high school with thousands of students, and we called ourselves “S.A.F.E.” which stood for “Student and Faculty Education.”

For me, this meant I could pursue my major obsessions at the time, foreign film, in particular, Ingmar Bergman, and music, in particular 20th-century music. There was a revival movie house in Chelsea called The Elgin, where I saw 38 Bergman films at a festival, and then I would amble into S.A.F.E. to talk about them with my teachers, who I called by their first names. I learned Ravel’s “Le Tombeau de Couperin” on the piano, to play for my classmates and teachers. I could also continue my research into drugs, alcohol, and underage sex but that is another story.

In my junior year, sick of high school altogether, my friend Richie was at Carnegie Mellon University, and I went to Pittsburgh to visit him there. I decided, after seeing two very elegant-looking men walking two Afghan hounds and holding hands walking across the cut, that I had to be there. I learned a bunch of piano pieces by Scarlatti, Beethoven, Hindemith, Brahms, and Leo Kraft, an obscure American modernist, I auditioned as a pianist, and got in for early enrollment. In the middle of my senior year of high school, at 17, I was already at college.

When I got to Carnegie Mellon University in 1973, the new album of that moment was Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark. Though I remember it as remarkable, and I played it all the time, and though the very mention of it roils all the feelings and memories of my first year of college, the pain, the freedom, the independence, the sex, the drugs, the alcohol, the longing, and the obsessions… by now, she was no longer a solo instrumentalist, no longer a troubadour. She had a band. There was electricity, arrangements, and drums, and I no longer felt like she was speaking to me alone. There were too many people in the room. The whispered intimacy and dailyness of Song to a Seagull, with sweet songs like “Sisitowbell Lane,” and “Michael from Mountains,” the risky a cappella quiet searing protest of “The Fiddle and the Drum,” and the dried flowers of Clouds, the old neighborhood clattering of Ladies in the Canyon, and the harrowing heartbreak, the Plathian confession of Blue, had given way to a more “global,” and “universal” sound. She was more commercial, more pop, more accessible, still fascinating, but each time, incrementally, a little more gone from me. She was less vulnerable, and she no longer needed me. She no longer broke my heart.

Then came her experimentations with jazz, where her songwriting style became more freestyle, meandering and formless. She got hip. When I listen now, it is a strange kind of hip… as if being who she was wasn’t bringing her what she wanted so she invented a new persona. Is being cool good for art? Cigarettes eventually robbed her of her soaring head voice, her purity, so she began to growl like a jazz singer, a trombone instead of a clarinet. Sometimes, she even sounded high, far away, and distant.

Though I didn’t lose interest, I definitely became a more impassive observer, curious, but less involved. I always bought an album when it came out. I liked Hissing of Summer Lawns, and Hejira very much for their urbanity, their glittering surfaces, but the “very much” of interesting, the “very much” of “ah, yes,” not the “very much” of crazy love. They were still brilliant, but for another audience. “Mingus,” Wild Things Run Fast,” “Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter,” and “Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm,” were less and less my style, and even, at moments, I thought, less focused, and not necessarily good. I didn’t get them. As far as Dog Eats Dog, and Taming the Tiger goes, I didn’t even purchase them. I didn’t purchase them? The distance from where I started to where I ended up is almost alarming. I couldn’t go on the journey with her; something I never thought I would say about Joni Mitchell.

This was a painful loss of innocence. But then, finally, after years, a veritable desert, she surprised me with Turbulent Indigo, and ESPECIALLY “Night Ride Home.” I HATED her setting of Yeats’ seminal poem “The Second Coming,” just as I loathed her song “Love,” which uses sections of Corinthians from the Bible, but I think “Cherokee Louise,” “Border Line,” Turbulent Indigo,” and “Night Ride Home” are truly great songs.

I LOVED that “Night Ride Home” started with a chirping cricket. She seemed activated, quirky and impassioned again. Honest. Connected to the world. She had made peace with the limitations of her voice. The smokiness was working in tandem with the subject matter, it was all of a piece. She was angry, and jaded, but pointedly so, and lyrical again. Once again, I could feel the form, the skeleton, the clarity. I felt invited back. But I have never returned to the place I started in, the blush of first love.

Do I have a right to say any of this? Joni Mitchell is a magnificent artist, entitled to as many phases as she likes. Who am I to judge which of these stages was meaningful, or produced better fruit. But, as I say in my introduction, I am writing here about me as well. My tastes, my aesthetic, which in many ways was shaped by her as well as all the artists I loved. But we change. Our tastes change. Our desires change. Our needs change. Our friends change.

Joni was back, she was great, she just wasn’t my best friend anymore. Sometimes, we will go anywhere an artist we admire takes us. We love their early period, their middle period, and their later period. I love all of Benjamin Britten’s music, truly I do, but his last opera, “Death in Venice,” based on Thomas Mann’s great novella, is my favorite opera of his. I love Beethoven’s late quartets most of all his work, and Faure’s late music is some of the most beautiful music ever written. Witness the way Bertrand Tavernier in his exquisite film “Sunday in the Country,” about an aging painter falling out of fashion with the times, uses Faure’s late music, to parallel the painter’s situation. Faure too, fell out of fashion, his light dimmed and eclipsed by impressionists like Debussy and Ravel, just when he was writing his loveliest, most aching music, I think.

And what of Sylvia Plath? Are not her last poems her most powerful? In “Words,” she writes, “Years later I encounter them on the road, words, dry and riderless, the indefatigable hoof taps. While, from the bottom of a pool, fixed stars govern a life.” A whole city could rise and fall on the power of those lines. And Shostakovich, my favorite Symphony of his is the 14th. There is only one more. Alas, we love what we love when we love it, and living is worth all of it, for those flickers, however long they glow. I love Joni’s early and early middle period, and her early late period. And there is this as well. When I moved into the world as an artist in my own right, when writing music and words became my life’s work, in some ways, I had to kill my heroes inside me. They were crowding me out. I needed them to fan the flame of who I would become, but then, I had to let those birds fly free. I had to soar in my own orbit.

At Carnegie Mellon, in my first semester as a pianist, something felt wrong but I couldn’t put my finger on it. Sitting in a practice room all day to perfect a Chopin Nocturne when I knew I would never in a million years be good enough to make it as a concert pianist seemed futile, and I did not feel I was able to express who I was as a pianist. Right before I got there, Stephen Sondheim had written his dazzlingly elegant score for Alain Resnais’ movie Stavisky — oh my God, Alain Resnais, the French director of Night and Fog, Last Year in Marienbad, and Hiroshima, Mon Amour! — and I listened to it over and over again. My fingers wanted to make something like that happen. I was also by this point, obsessed with Sondheim’s Follies. I had an aching to express the same brokenness and disappointment he expressed in that musical, or Ingmar Bergman expressed in all of his movies.

I wanted to BE the music, not just PLAY the music. I wanted to make something great and profound and moving like them. I was discovering new composers like Olivier Messiaen with his swirling nattering birds, and devotion, and Hans Werner Henze with his post-WWII ferocity and angularity, and music was taking hold of me in a new way, devouring me. There was a blind pianist named Lynn who was obsessed with Shostakovich. “Shostie” she called him. She could play anything from any of his symphonies on the piano and she WAS music, there was no separation. I loved her and I envied her. I knew, I couldn’t BE music by being a pianist, so I became a composer. This act, this decision, was walking into the light for me. I have slowly since that moment been finding my way, and the road, though painful and paved with equal measure ecstasy and self-loathing, is no doubt the road I want and am meant to travel on.

My first attempts at CMU were settings of poems, all the poems I loved, and poems by the poets I had met at school. I took writing classes as well in order to write my own poems and lyrics. By figuring out, deciphering the architecture of a poem, and creating, or attempting to create, an equivalent musical architecture, I started finding a way to construct things, buildings to house my thoughts and feelings. I wrote music for productions in the drama department, for plays by William Inge, and Christopher Marlowe and Bertolt Brecht. Then I became an actor. Was this a good idea? In my drug-addled mind it seemed to be, though my parents thought I was crazy.

But the most interesting, the most charismatic, the most beautiful people at CMU were the actors, and I wanted to be one of them. I envied how in their bodies they were. I needed to see what that was like for a little while. It lasted a year, and it was an incredible education. Learning the inner workings of plays by Ibsen, Chekhov, Williams, Ionesco, Brecht and O’Neal, learning what goes into creating characters, embodying them, and most of all, taking the kind of risks I had never taken before, sometimes succeeding, sometimes falling on my face, in front of my extremely talented classmates. It was good for me. It broke the isolation of music. And then, after three majors and three and a half years, I quit. But here’s the thing, I write for the theater. I write opera, and musicals, and ballets, and I even consider every art song a miniature piece of theater, a showcase for a singer, an opportunity for a close-up, so somehow it all made sense. We have some urge towards becoming who we know we are supposed to be, and I was just listening to it. I have been all along.

In her song “The Circle Game,” which, by the way, is the song she ended the Carnegie Hall concert with, inviting Neil Young, David Crosby, Graham Nash, and even Paul Simon (!) to come up and sing with her, having the house lights brought up so the audience could sing along as well, Joni Mitchell writes “And the seasons they go round and round, and the painted ponies go up and down. We’re captive on the carousel of time. We can’t return, we can only look behind from where we came, and go round and round and round in the circle game.”

There is a later chapter to this story…one that makes all of this, starting with my sister’s article, particularly poignant, and circular. In the early 2000s, I met Judy Collins. Stephen Holden, the critic from The New York Times, became a fan of my music and he put us together thinking Judy might want to sing some of my songs. I sent her a bunch of recordings and scores. She was lovely and very complimentary, getting in touch with me right away. We became friends. One day after lunch at a Café on my corner, fittingly called Café Mozart, she came back to my apartment. Upon seeing the Knabe upright my mother charged for me on the installment plan at Macy’s, when Macy’s truly sold EVERYTHING, she sat down and began to play, singing her stirring song from 1989, “The Blizzard.” I had so many feelings standing there. This is Judy Collins, I kept saying to myself over and over, ‘Judy Collins, in my house, playing and singing at my piano!’ I felt awed and honored. Then, a few years ago, Judy was performing at Café Carlyle. She included my song “A Horse With Wings.” She sang it beautifully, and I beamed, shone with pride. All I could think of, the whole night, was that photograph in my sister’s article in 1969, Joni and Judy wandering through the woods, and how magical, generous and utterly unpredictable life is.

Joni Mitchell’s letter from 1970 hangs over my piano, framed in gold. Even the envelope is framed. It may be my most valuable possession.

And still, on all those talk shows, when they ask at the end if there were one person you could meet, alive or dead, who would it be? I would answer, Joni Mitchell. I would like to talk to her. I would, of course, ask her about the dress. And if I could, I would even like to sing to her.

Afterward

There was a tribute to Joni Mitchell on TV, where many big stars performed her songs, while she sat up in a box chain-smoking and observing the festivities, accompanied by the daughter she had reconnected with after she gave her up for adoption (“Little Green.”) She NEVER, not once, looked happy. She looked agitated and fidgety. I thought, how I would feel if I were her in this situation? I think, in so many of Joni Mitchell’s great songs, that her decisions are very pointed, and composed. They are not like jazz or pop songs that call for and profit from interpretation, in fact, they suffer.

What is beautiful about so many of her songs, is the way she does them. If you flatten her harmonies, if you are even a fraction less imaginative harmonically than she is, you change the song. So I felt, her songs were in essence, diminished that night. They lost their luster in so many of the performances. In the end, though, something strange and profound happened. Joni Mitchell walked onto the stage. Unlike all the other glamorous TV ready, Hollywoodized performers that night, which is not a judgment of their capabilities, but a personal observation of their official readiness, Joni practically galumphed onto the stage, with very little stage savvy… just a real person, awkward, strange in the surroundings, ready to humbly deliver her wares. It wasn’t particularly gracious. I don’t remember her thanking everyone or anything like that. But she sang “Both Sides Now,” and the room filled with everything that is glorious and real, moving and truthful about Joni Mitchell, everything that is visionary, beautiful and wise. She is, and must be, an embodiment of her work. Its greatness resides in her doing it.

After the Afterward

I realize, it is foolhardy and unfair to judge an artist who I admired in my teens by the standards I have now in my sixties. As Stanley Kunitz says, in his great poem, “The Layers,” “I am not who I was, though some principal of being abides, from which I struggle not to stray.” Whoever I was then, Joni Mitchell, had an enormous amount to say to me, and for that, I am grateful. What life has done to me since then, to create, and then deepen my wounds, and reshape my needs, both in art and life, is not her fault. Let her remain in that bubble of beauty, when life was simpler, and my older sister could recommend something, and because I loved and admired her, I would listen.

Ricky Ian Gordon is an award-winning composer, nominated, in fact, for a Grammy this year. His next opera “Intimate Apparel,” commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera and the Lincoln Center Theater will premiere at the Lincoln Center Theater in Fall 2021. This article is from his forthcoming memoir to be published in 2022 by Farrar Straus & Giroux.