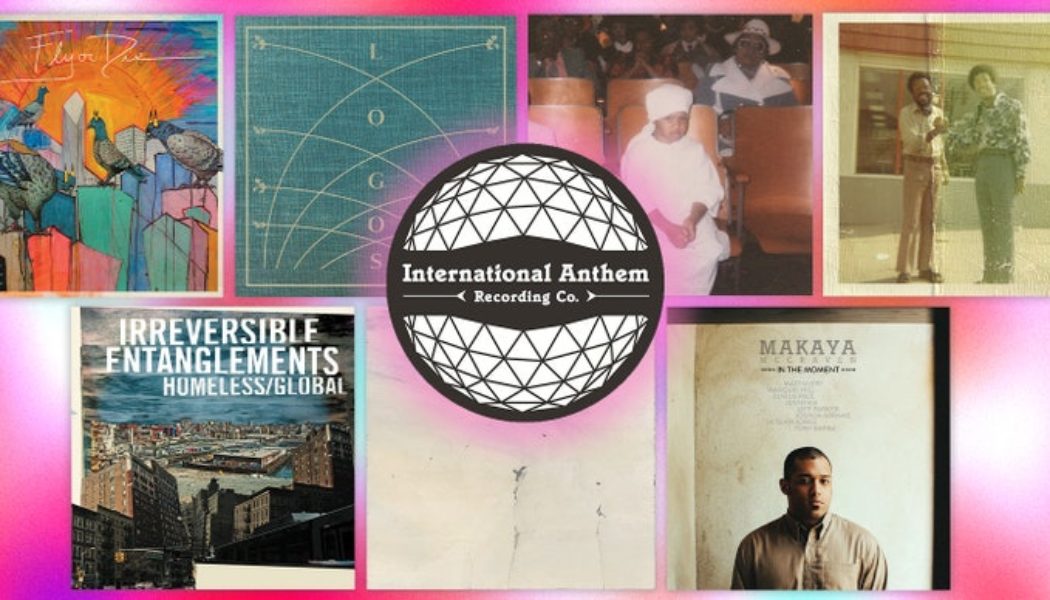

Midway through “burning grey,” from her riotous third and final album Fly or Die Fly or Die Fly or Die ((world war)), jaimie branch issues an exhortation that could serve as her artistic mission statement: “Don’t forget to fight.” Whether leading her Fly or Die quartet or working as a prolific collaborator across scenes and cities, the trumpeter, composer, and vocalist, who died of undisclosed causes at 39 last year, made music from a position of joyful defiance.

Her background was in jazz, but she had little regard for putative genre distinctions, pulling in the syncopated rhythms of Latin and Caribbean music, the melodic clarity of folk song, the swirling textures of psychedelia, the abstraction of free improv, the swagger of hip-hop, the pugilism of punk rock. Her commitment to each note didn’t just make these connections between various canons seem plausible; it made the notion of their separation seem absurd. There are inherent risks to such agnosticism about style. For the enthusiastic amateur, it can betray a lack of focus; for the dispassionate professional, a belief that idioms are exercises to be mastered by rote. For branch, whose consummate technical ability never got in the way of her raw passion—or vice versa—it is simply evidence of the conviction that all of these ostensibly divergent branches grow from the same tree. And at its root, as she and her collaborators demonstrate on ((world war)), is the will to fight, to dance, and to survive.

branch had very nearly completed ((world war)) when she died. Her family members and bandmates consulted her notes to finalize details like mixes and track titles before its release. Given those circumstances, it is tempting to hear the album as a requiem, or a grand finale for her brief but impactful career. Its structure, opening with a heroic fanfare of timpani and electric organ and closing with a funereal dirge, does not initially discourage that interpretation. But on further listening, it feels less like an ending than a blossoming cruelly cut short. Though listeners of branch’s previous recordings with Fly or Die will have no trouble recognizing ((world war)) as the work of the same bandleader, they may also be struck by the number of new paths the album opens in her music.

Ideas that showed up in the margins of previous records now assume central positions. The calypso-inflected major-key melodies that came across like a lark on “simple silver surfer,” from Fly or Die II, reach nearly symphonic proportions on “baba louie,” ((world war))’s nine-minute centerpiece. branch’s roughshod and vehement vocals, absent from the first Fly or Die album and tentatively present on the second, are a driving force of the third. She is decidedly not a jazz singer, at least not in any traditional sense: She shouts, beseeches, howls wordlessly, even croons a sort of country song. The lyrics mostly favor pragmatism over poetry, plainspoken calls for resistance to the status quo. Like previous Fly or Die albums, ((world war)) often has the feeling of a raucous block party. As its master of ceremonies, branch never lets us forget that there is not just escape to be found in coming together and letting loose, but solidarity, too.

((world war))’s most striking departure from branch’s previous work comes in “the mountain,” the aforementioned country tune, a reworking of “Comin’ Down” by Arizona twang-punks the Meat Puppets that is drastic and inspired enough to merit its new title. In stark contrast to the rest of the album’s rollicking maximalism, its instrumental accompaniment consists almost entirely of Jason Ajemian’s pizzicato double bass. Ajemian sings lead, and branch harmonizes. Neither is a virtuosic singer, but showiness is not the point. The lyric, about the fitful search to transcend everyday toil, monotony, and misunderstanding, benefits from the humility of their performance. The recording is as sparse and unslick as could be: We hear collective deep breaths, a bit of branch muttering to psyche herself up, the sound of the two musicians physically shifting around the microphone. Given the bare-bones arrangement, branch’s trumpet solo, when it arrives near the song’s end, comes as a delightful surprise, even on an album by a trumpeter. There’s something jaunty and insouciant about the solo’s plainness, especially the simple three-note run that provides its emotional climax, coming at a spot where another player might have attempted a more impressively elaborate gesture. Its self-assuredness and refusal to bow to anyone else’s ideas about presentability obliquely bring to mind the cocked baseball cap that branch often wore onstage.

The hushed intimacy of “the mountain” is the exception on an album otherwise characterized by jubilant ensemble playing. One easy reference point is Miles Davis’ electric music of the 1970s: avant-garde and populist at once, following the certainty that even the most complex dissonance will go down easy if it’s set to a good enough groove. Where Davis took inspiration from the sturdy 4/4 of James Brown or Sly and the Family Stone, branch favors the slippery polyrhythms of reggaeton and dancehall. Like Davis, she is the clear star of the show when she picks up her horn, but she also knows when to lay out, focusing instead on guiding and conducting her accompanists’ gale force.

Ajemian and drummer Chad Taylor play as if the fate of the universe rests on their ability to get you dancing. Cellist Lester St. Louis flits between roles, one moment contributing to the rhythm section’s unstoppable churn and the next spinning out melodic leads or sul ponticello cyclones of noise. At one point in “borealis dancing,” he ascends through a series of sustained single notes, the increasing frenzy of his bowing creating an almost unbearable tension against the conversational calm of branch’s trumpet lines. The ensemble often works like this: While one person shreds like crazy, another stays cool. It’s part of what keeps ((world war)) feeling so dynamic, giving the music space to breathe despite its instrumental density and full-throttle tempos. Within the larger trajectory of each piece, there are many smaller overlapping arcs of excitement and comedown, each following the chaos logic of a four-person improvisatory mind-meld.

The rowdy camaraderie of the improv is so powerful that it can be easy to overlook the care and sensitivity with which branch composed and arranged these tunes. Themes reprise unexpectedly; formerly dueling voices slide without warning into choreographed tandem. The longer pieces tend to follow a rough A/B structure, with a burst of body-moving energy to get them going and a turn into headier territory to bring them home. In “borealis dancing,” the band downshifts on a dime into head-nodding half-time; in “baba louie,” calypso melts eventually into ghostly dub. “take over the world” begins on a dembow rhythm played with the addled ferocity of hardcore; in branch’s stuttered declaration of intent to “Take over the world/And give it back to the land,” the song’s fusion of punk and Caribbean music comes across like Bad Brains if they were more focused on the dancefloor than the mosh pit. In its second half, Taylor takes up an effortlessly funky New Orleans-style snare-drum groove, St. Louis begins bowing an insistent two-note figure on his cello, and a delay pedal mutates branch’s voice into increasingly alien shapes. The rhythms keep the music rooted in the traditions of the Afro-Caribbean and Latinx diasporas, and the electronic contortions send it toward some imagined utopian future.

Music of all kinds suffered a significant loss with branch’s passing last year. ((world war)) provides a precious document of her artistry at the end of her life, and a glimpse of where she might have taken it next. Even more important: It is a joy to hear, and a reminder that the struggle for a better world is a beautiful and worthwhile endeavor, despite the many powerful voices that work daily to convince us otherwise. branch fought the good fight until the very end.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.