Last month, Square’s Dorsey prodded the government (via tweet, of course) to let his payments company and others in the fintech industry help figure out how to get Americans their money in a hurry. Schulman, of PayPal, says he pitched a business acquaintance, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, about distributing government funds via PayPal. This week, the Treasury Department approved both PayPal and Square as distributors of the $350 billion in small-business loans that were also part of the stimulus package.

To some, however, a pandemic-triggered decline in cash is nothing to celebrate. Cash is an essential financial tool of the millions of Americans who either don’t have access to banks or credit cards, or who opt to not make use of them. (While it’s still possible to use PayPal and Square without a bank account, such as by transferring funds to a prepaid debit card, the services are designed around banked Americans — not to mention ones with smartphones and broadband.)

Last year, the city of San Francisco passed a ban on cashless stores; that’s one reason Standard Cognition’s contactless demo store, on the edge of the city’s tech-heavy SoMa neighborhood, still takes dollars, which are collected through a “store ambassador.” (The store is currently closed because of the coronavirus.)

One unlikely place to look to better understand the tensions caused by the move away from cash: the Washington, D.C.-launched salad chain Sweetgreen. In 2016, the fast-casual food retailer stopped accepting cash. There was outrage: The company, the thinking went, was blocking cash-preferring patrons from getting access to healthy foods. The company rolled back the ban two years later. But the company designs at least some of its stores to highlight the most efficient way to get your hands on a kale Caesar salad: pay for your order online first, breeze in, pick up your meal from a designated shelf, and be back out the door in seconds. This still leaves cash-payers a step behind: Skipping cash lets you skip the line.

That hybrid, bets PayPal’s Dan Schulman, is what’s likely to stick post-pandemic: we’ll go back to shopping out in the physical world but stop paying in cash, instead paying online either before or after.

PayPal and Square have much to gain by looking like innovators helping the country in its time of need. For one thing, on topics like taxes and insurance, fintech firms like these are attempting to carve out more favorable regulations for the still-young industry. The Electronics Transactions Association, a D.C.-based lobbying group, put out a Covid-19 briefing document saying the payments technology industry stands ready to move money “in a safe and effective manner with little to no physical contact, in-person and online.”

In some countries, mobile banking is seen as a tool for economic inclusion. Kenya’s central bank has found that that country’s M-Pesa system, named after the country’s currency, has boosted access to financial resources. The service, backed by major telecoms, works by tapping the country’s vast network of prepaid airtime resellers to act as cash-exchanging microbanks — often by young people in cities eager to send money back to the rural areas in which they grew up.

The M-Pesa model, though, hasn’t taken off in the U.S., where there is less demand — even with access challenges in the U.S., there is a far wider variety of trusted, safe, traditional banking options than in Kenya — and less infrastructure to support it; for one thing, the pay-as-you go plans that put users in frequent contact with bricks-and-mortar resellers are less prevalent.

And there are concerns that a quick, pandemic-inspired wholesale shift to digital money will instead hurt unbanked Americans. In part to address that worry, in recent weeks House Democrats have floated a “digital dollar” plan that would equip Americans with simple online accounts that would make it easy for the government to distribute direct payments to Americans, whether stimulus checks or, someday, so-called universal basic income.

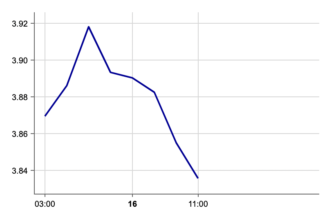

And the importance of getting those payments fast only grows with gathering momentum in Congress for more cash infusions to Americans coping with coronavirus.

PayPal’s Schulman sees all of this as part of a coming shift: Every transaction that we choose to do virtually instead of with cash builds up our muscles for the change, getting us comfortable with never touching that Alexander Hamilton bill again. And those are muscles, he argues, we’re going to need in the near term, especially as unemployment skyrockets.

“There’s now multigenerational distress being felt and therefore the need for there to be some sort of common platform amongst family members,” Schulman says. Translation: a grandpa who figures out how to Venmo his grandkids some birthday money using the app’s user-to-user functionality is one who knows how to Venmo his family members cash when they’re in real economic need — or to get Venmo’d cash when he is in need.

Already, we’re adapting our behaviors. PayPal reports that in the first week of March, payments tagged with its medical mask emoji—often to canceled housekeepers, babysitters, hairdressers—grew 375 percent.

Of course, there’s another possibility. And that’s that cash comes roaring back after coronavirus, perhaps something like the handshake, a practice that seemed odd, even foolhardy during the pandemic but that we return to out of habit or, as it turns out, it still has its place.