Imagine that, over the past year, Facebook had managed to acquire the battle royale game Fortnite, the kid-focused game creation engine Roblox, and the best-selling game of 2020, Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War.

For many reasons, such a spree of acquisitions would never happen. One of the biggest is that antitrust scrutiny has made it increasingly difficult for Facebook to acquire anything that resembles a social network. It was more than a year ago that the company bought the moribund GIF search engine Giphy, which had few prospects for success as a standalone company; the United Kingdom’s competition watchdog has so far blocked the deal from closing, warning the acquisition would somehow harm Facebook’s competitors.

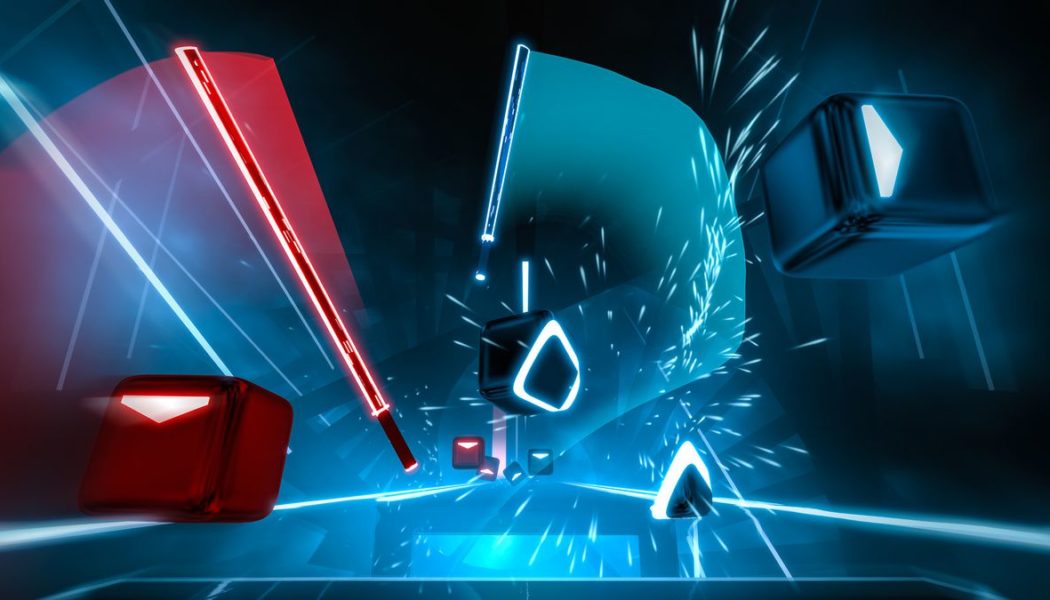

And yet if you look at the virtual reality landscape, Facebook has made a series of acquisitions that are roughly analogous to the fictional shopping spree I describe above, if on a much smaller scale:

The company’s other VR studio acquisitions include Sanzaru Games and Ready at Dawn.

Alex Heath, a reporter at The Verge who has closely covered the rise of AR and VR technologies, observed on Twitter recently that Facebook’s acquisitions in the space resembled its most famous bets on nascent technology from years ago: the purchases of Instagram and WhatsApp, which helped the company cement its position as the dominant player in social networks.

“Facebook is going to probably have a near-monopoly in VR software before it even matters,” Heath tweeted. “Facebook will have literally reinvented itself for a new paradigm shift in computing by the time regulation gets around to addressing it in its current state.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13621124/30814989187_f608551022_k.jpg)

Whether or not you think Congress should intervene to regulate tech acquisitions, it’s undeniable that the process moves slowly. Facebook bought Instagram in 2012 and WhatsApp in 2014; a congressional antitrust inquiry didn’t begin until five years later; and a bill that would require heightened scrutiny of tech platform acquisitions was not introduced into Congress until… Friday. (OK, fine, the insurrectionist Sen. Josh Hawley introduced a bill to ban all platform acquisitions, period, in April, but his bills are better thought of as Fox News op-eds than as serious efforts to regulate the industry.)

I think the Federal Trade Commission should be more skeptical of tech giants acquiring their direct competitors, but I’m not sure a bill that defaults to banning acquisitions is the best approach. Acquisitions are part of the lifeblood of Silicon Valley, and the money that they return to investors gets re-invested in the next generation of entrepreneurs and technologies. You can encourage competition in lots of ways without banning M&A. And in any case, it’s hard to imagine a bill like this one garnering much support from Republicans, Hawley’s bill notwithstanding.

At the same time, let’s say you believe Facebook’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp set back the consumer internet for a few years — until TikTok emerged, anyway. Wouldn’t you want to apply as much scrutiny to Facebook’s current shopping spree as you’re applying to moves it made as long as nine years ago?

The answer to that question likely depends on how large you think the market for virtual reality headsets and its attendant software ecosystem will someday become. Currently the market is small — Facebook’s Oculus platform had sold fewer than 10 million units as of January. The PlayStation 4, by contrast, has sold over 115 million units during its lifetime; Apple sold almost 80 million iPhones in the last quarter of 2020 alone.

If you think VR will grow to roughly the size of a major console gaming platform, maybe you’re not concerned how many studios Facebook is buying. Console manufacturers buy game studios all the time — Microsoft’s acquisition of ZeniMax Media, owner of Bethesda Software and its many popular franchises, was last year’s mega-deal in the space — and no one seems to have too many concerns that any one console is developing a monopoly.

If, on the other hand, you think Oculus could grow to a size more closely resembling a major desktop computer manufacturer, like Dell, perhaps you would eye its acquisitions with more scrutiny. To lay my cards on the table: I think it eventually will.

Facebook still hasn’t released sales figures for the Quest 2 headset, and I’m told Playstation VR has sold more units overall. But we know that Quest 2 drove a 156 percent year-over-year increase in Facebook’s non-advertising revenue in the last quarter of 2020. Even on a relatively small revenue base, that might make VR Facebook’s fastest-growing business.

Everywhere you look, you find signs of Facebook’s growing confidence in its VR platform. CEO Mark Zuckerberg has given frequent interviews on the subject over the past 12 months, among other things positioning AR and VR as an enterprise software platform as well as a place to play games. The company has hired more than 10,000 people to work in its Facebook Reality Labs hardware division.

In short, there’s more evidence that VR will be huge amid Facebook’s run of acquisitions today than there was evidence that Instagram was going to be huge when Facebook bought it in 2012, before the app had even 50 million users.

None of that is to say that I think VR will overtake smartphones as the world’s biggest computing platform. And it’s also clear that Facebook has real competition as it tries to build out the mixed-reality future. Snap is also building impressive hardware and software in that space, focused on its Spectacles glasses and growing developer ecosystem around them. Apple, which is working on a headset of its own, has made at least four acquisitions of mixed-reality companies in recent years itself.

It may also be that Epic Games makes Fortnite the Fortnite of VR, and Roblox makes its platform the Roblox of VR, and Facebook’s efforts in that space wither.

Facebook told me its reasons for acquiring so many game studios are straightforward: it wants to accelerate the growth of a still-nascent industry by ensuring top-flight gaming experiences are widely available. It’s a very small player in the gaming industry, the company said, but hopes its acquisitions will be good for both developers and users.

“That’s all true — but it doesn’t doesn’t mean it isn’t going to be an issue in six or eight years,” Heath told me over the phone Wednesday. From Heath’s perspective, the more consequential aspect of Facebook’s acquisitions is that it will tie up a significant amount of VR talent at one company for at least four years while their options from the acquisition vest.

“There are not that many companies doing this,” Heath said of the VR industry, “And the people that are good either already work at Facebook or they’re buying them.”

None of this will much matter if the VR industry fails to live up to its most recent round of hype. And failing to live up to the hype is perhaps the signature feature of the VR industry for its entire lifespan so far.

But if VR becomes a part of our daily workflow as well our daily entertainment, and Facebook becomes the market leader in that space, we may be in for another global conversation about how a tech giant successfully used its market power to take over an adjacent industry. If that’s to be the case, it strikes me that the time to have that conversation is now — while the foundation is still being laid, one minor-seeming acquisition at a time.