Li-Fi is here to join Wi-Fi as a physical networking layer.

Share this story

We’ve known for over a decade that blinking light bulbs can transfer substantial quantities of wireless data, not just dumb infrared commands to your TV. Now, the IEEE standards body behind Wi-Fi has decided to formally invite “Li-Fi” to the same table — with speeds of between 10 megabits per second and 9.6 gigabits per second using invisible infrared light.

As of June 2023, the IEEE 802.11 wireless standard now officially recognizes wireless light communications as a physical layer for wireless local area networks, which is a fancy way of saying that that Li-Fi doesn’t need to compete with Wi-Fi. Light can be just another kind of access point and interface delivering the same networks and/or the same internet to your device.

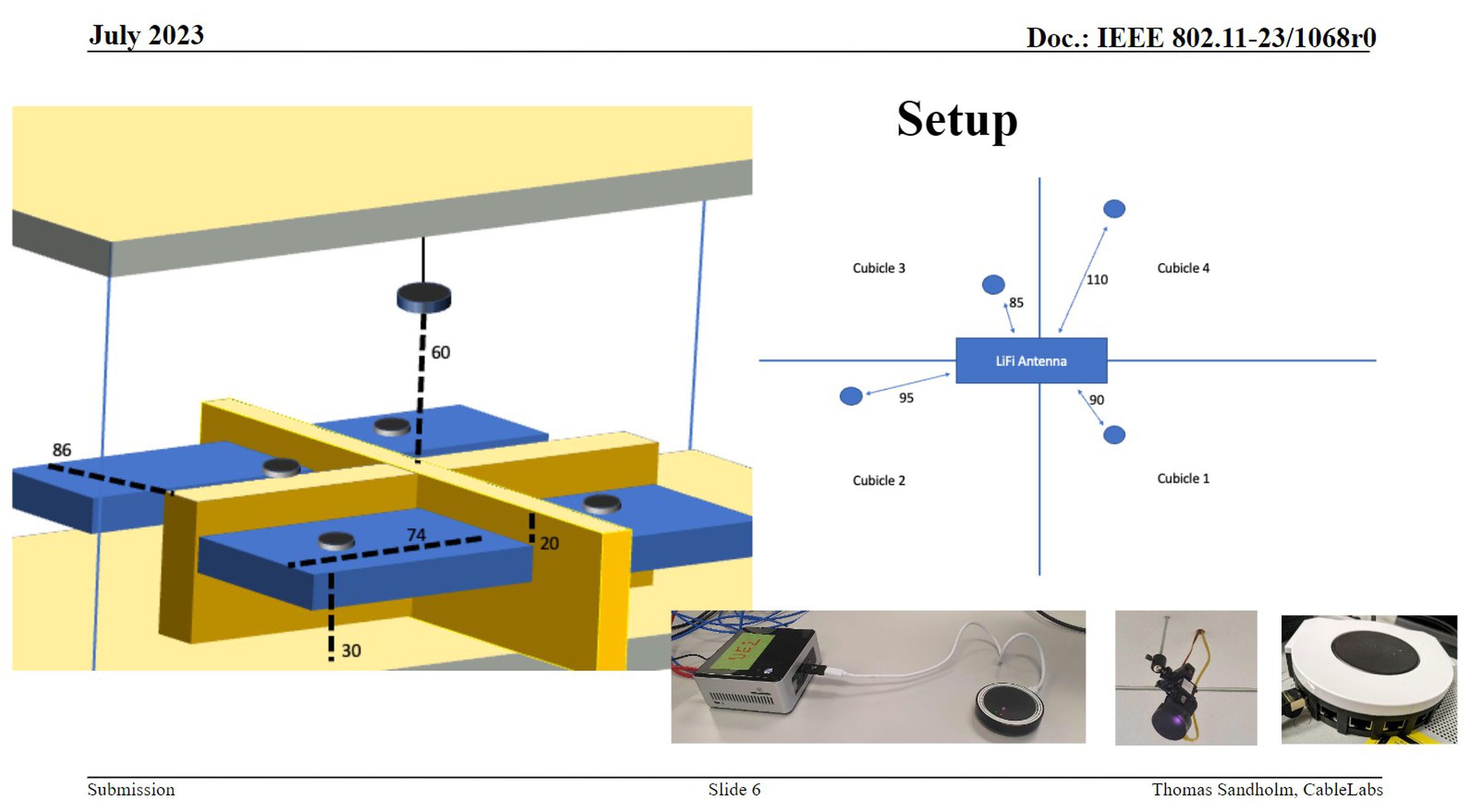

In fact, at least one IEEE member has been experimenting with networks that use Wi-Fi and Li-Fi simultaneously to overcome one another’s disadvantages, intelligently steering some office computers to Li-Fi vs. Wi-Fi to improve the entire network.

See, Li-Fi products aren’t actually new: companies have tried to sell them for a number of years. There’s even already a competing standard, the International Telecommunication Union’s G.9991, which appears in data-beaming bulbs from Philips Hue maker Signify among other things.

These companies have been banking on the fact that light can deliver a speedy, private, direct-line-of-sight connection with no radio interference — amid concerns that lighting conditions can vary drastically and it’s all too easy to accidentally sever a line-of-sight connection. My colleague Jake illustrated the pros and cons when he tried a Li-Fi lamp in 2018.

In its experiment writeup, CableLabs doesn’t deny that Light Communication (LC) has room for improvement. “LC range is very sensitive to irradiance and incidence angles making dynamic beam steering (and LoS availability) attractive for future LC evolution,” reads one line in the study.

“Enterprise Wi-Fi and state-of-the-art LC performance on par but LC reliability needs to be improved. A possible approach is the use of multiple, distributed optical frontends,” reads another.

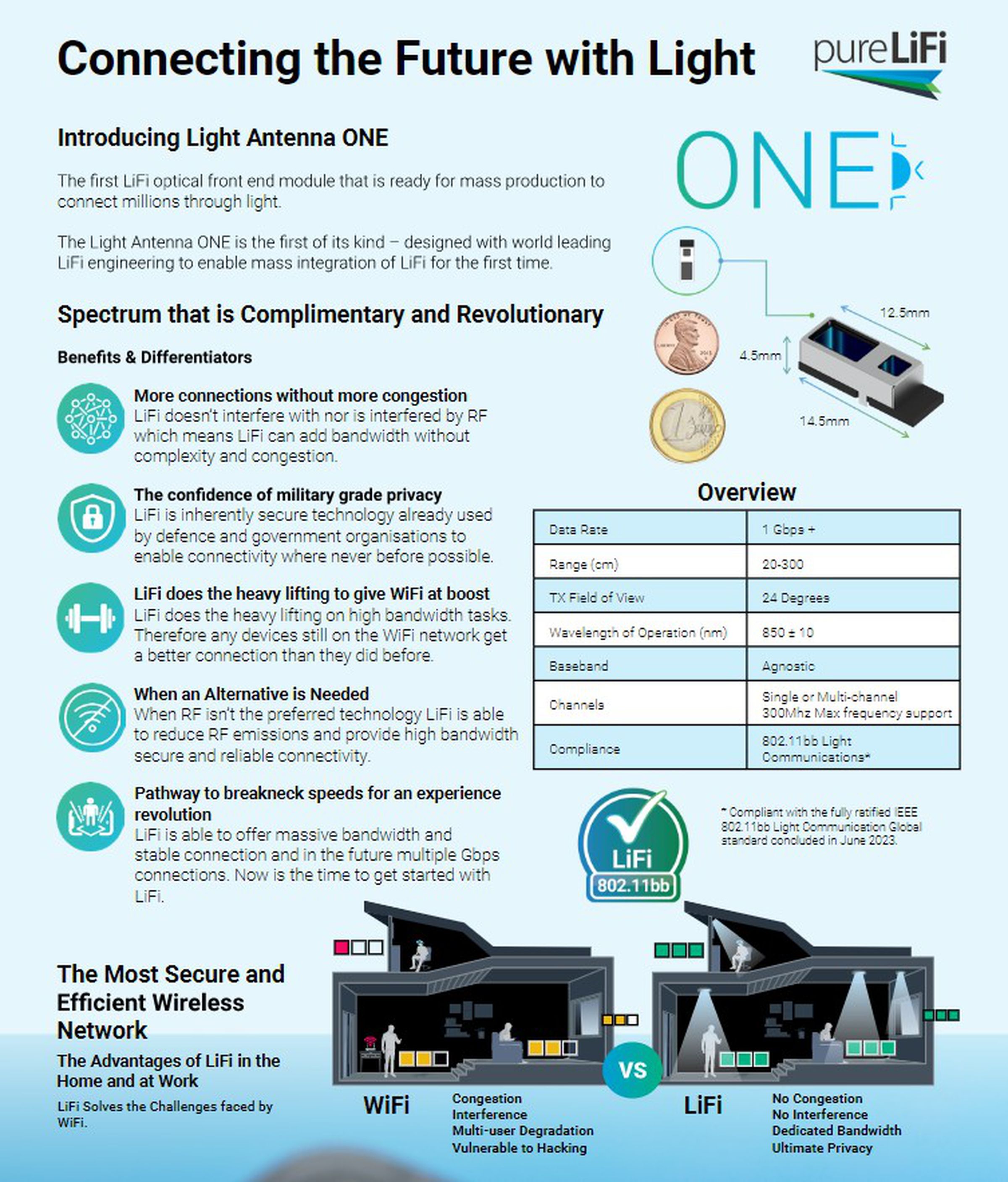

The reason we’re hearing about this now isn’t because the IEEE made a big deal about it, by the way — it’s because the company that hired the man who coined “Li-Fi,” Dr. Harald Haas, really wants to take this opportunity to sell its newest product, and task group member Fraunhofer wants to be recognized for its contribution.

PureLiFi just launched the Light Antenna One in February, a module small enough it can theoretically be integrated into smartphones, which it claims can already deliver over 1Gbps depending on the use case. (It’s only rated to communicate with devices that are under 10 feet away, and it has a 24-degree field of view when transmitting back.) PureLiFi says it’s already compliant with the 802.11bb standard and is ready “to enable mass integration of LiFi for the first time.”

The IEEE task group has a 59-page overview (PDF) of 802 light communication standards if you’d like to learn more, including links to a number of video tech demos. It also mentions parallel efforts on 802.15.13 for industrial and medical applications.