“Welcome to the simulation” read a card inside the package sent to me by Simulate, the company responsible for the Nuggs brand of plant-based chicken nuggets. Inside the package, nestled among some dry ice, were what looked like several specimen bags. Each bag contained two Nuggs, from version 1.0 to version 2.0 with six versions in between. They were each carefully labeled: “Project: The Verge. Variant: V.1.6.” As I transferred the cargo to my freezer, I felt less like I was putting away some groceries and more like I was participating in a lab experiment.

That’s the kind of energy Simulate is going for. Its branding is simultaneously silly and self-serious, and it’s deliberately steeped in internet culture. The Nuggs Instagram is almost entirely memes, with product announcements interspersed sparingly. “The name Nuggs is funny to most people, so we kind of leaned on that,” says Ben Pasternak, the company’s founder.

Jokes aside, Simulate, founded in 2019, is part of an industry where the competition is only getting more serious. Meat alternatives have been around for decades — Morningstar Farms was founded in the mid-1970s — but the last few years have seen an explosion of similar products as companies have gotten better at mimicking meat. A combo platter of advanced food tech and concerns about the sustainability of factory farming has made more people than ever willing to give not-meats a try.

The giants are Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods, both of which make plant-based patties that are meant to be as indistinguishable from beef as possible, going so far as to make them “bleed.” In the chicken nugget space, Beyond Meat paired up with KFC to offer plant-based nuggets at select locations of the chicken-based chain. Morningstar Farms recently partnered with Disney to bring Mickey-shaped nuggets to the freezer aisle. Even Big Chicken companies like Tyson have plant-based offerings now.

Which brings me back to Simulate, Pasternak, and my freezer full of experimental Nuggs. Pasternak sees Tyson as competition, but he’s more interested in putting his nuggets head-to-head with its chicken-based products.

Unlike other companies that keep most of their development behind closed doors, Pasternak says he wants to “operate from a place of truth,” showing everyone the changes Simulate’s recipe has gone through. When I was offered the chance to peek inside the lab (virtually) and try every single version of the company’s Nuggs, I figured why not. You know, for science.

Each version of Nuggs comes with release notes, similar to software updates. “Nuggs 2.0 includes fixes and improvements,” says the Simulate site. “Enables a close to indistinguishable chicken flavor.” You can only buy the latest version (in this case, Nuggs 2.0), but the notes for each past version live on the site. Looking through the notes while eating each Nugg added some fun insights to my experience. Version 1.5, which “enable[d] decreased sodium content,” did indeed taste less salty than Version 1.4.

Pasternak began his career building software, which explains why software updates show up in Simulate’s branding. He thinks of Simulate as a nutritional company with a software framework, where new iterations of the product are constantly being developed.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22342542/Image_2.jpg)

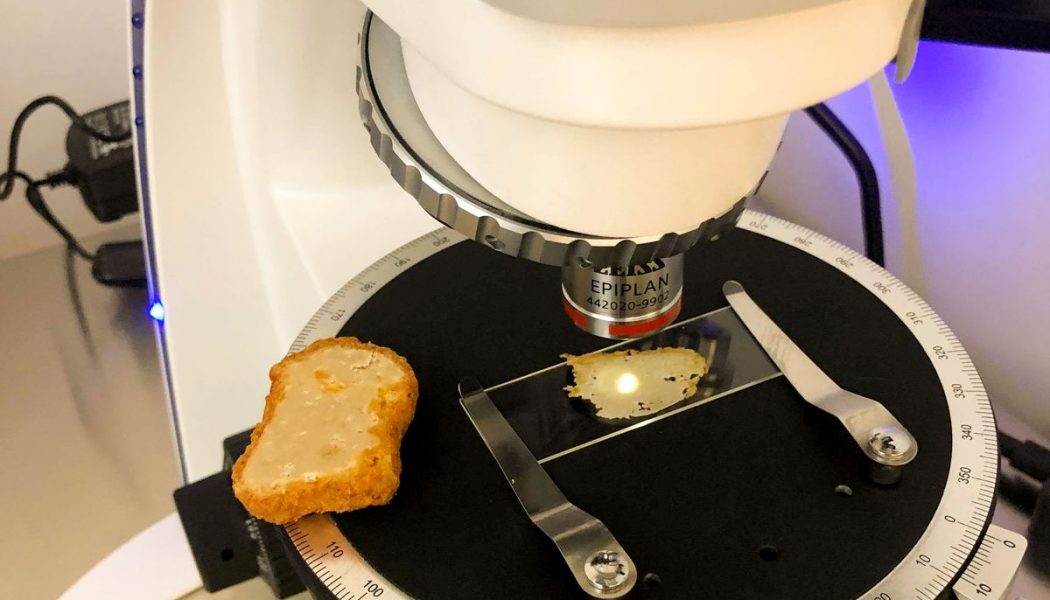

And there have been plenty of iterations. Doug Henderson and Bob Schultz, the Simulate food engineers who spend their days poking and prodding simulated nuggets, say that for every version of Nuggs released, there were hundreds more tested in the lab. They use devices that press, squeeze, and tear the Nuggs to measure and track tiny changes in their cohesiveness, chewiness, and springiness.

Between Versions 1.6 and 2.0, they put together a database of every plant-based meat product on the market so they could track and compare them to Nuggs. The constant testing and comparison led them to switch from pea protein — which Schultz says is an “immature technology” with several texture and flavor issues — to wheat and soy proteins.

My own judgment of the Nuggs was much less rigorous. I have not eaten a nugget that originated from an actual chicken in about 14 years, and I therefore am less than qualified to say how close in taste and texture Nuggs and chicken nuggets are. I can say that my face journeyed from a grimace at a strange aftertaste in Version 1.0 to a contented nod at the crunch of Version 2.0. I didn’t get to experience the Simulate BBQ sauce, but I did divide my duos of Nuggs for a highly scientific taste test. For each version, I tried one Nugg plain; these were my control group. I added hot sauce to the other for an extremely research-driven reason. (I really like hot sauce.) The verdict: they are very good vehicles for hot sauce.

I’ve never been particularly interested in products that aim to perfectly re-create meat. The idea grosses me out, even though I appreciate the novelty. But Pasternak sees Nuggs as a product that should appeal to all people, vegans and meat lovers alike. (Though the current price of $35 for 50 Nuggs might dissuade people in either camp.)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22342576/NUGGS_2020_0495.jpg)

Part of Simulate’s brand mission is to remain “non-preachy.” The people behind the company aren’t pushing a specific vegan or vegetarian agenda — “We wanted to not use any of the V words,” Pasternak tells me — they just want to make a good nugget. “We don’t want to tell anybody that this is a healthy food,” says Schultz, “we just want it to be the best chicken nugget experience you possibly can have.”

That makes sense since plant-based doesn’t automatically equate healthy. “We didn’t evolve to eat ultra processed foods and these meat substitutes are ultra processed foods,” says Marion Nestle, a Nutrition and Food Studies professor at NYU. “People would be much better off eating real food.”

Other experts take a softer stance: these aren’t health foods, but they are at least healthier than real nuggets — which, for the record, were also developed in a lab. Nuggs are processed, but they’re lower in cholesterol, a major contributor to heart disease. “If you’re taking that cholesterol out, and you can provide consumers with an alternative, then why not?” says Jillian Semaan, director of food and environment at Earth Day Network, an environmental activism nonprofit. As the Simulate site boasts, Nuggs “kill you slower.”

Simulated meats are also better for the planet, says Semaan. There’s no livestock involved when making meat from plants, meaning there’s less land required and no greenhouse gas burps. “We need to take a closer look at how we’re using our resources,” she says. Whether it’s Nuggs or other plant-based foods, “it’s kind of a no-brainer when it comes to having a sustainable place for all of us to live on.”

Pasternak hopes that simulated meats will become more popular than their animal-based counterparts in the next few decades. Semaan isn’t sure the tide will turn so quickly, but she does see a shift happening. “I think people are taking a closer look at what they’re eating, how food is grown, and what foods that they can consume,” she says. “That’s going to be for the betterment of themselves and the planet.”

I could pretend otherwise, but I really wasn’t thinking much about the planet, or my own health, while I was munching on the different variations of Nuggs. My deepest thoughts were more along the lines of “This first version tastes like a shoe,” and “There’s a nice amount of seasoning in this breading.”

Personally, when I’m staring down the shelves in the grocery store, taste and ease of preparation are further toward the front of my mind than a product’s environmental impact. Ultimately, even after going through the entire experiment, I still don’t know if Nuggs taste like chicken or if they will be the future of sustainable food. But I did find that they were enjoyable enough to eat when a hankering for nuggets strikes — along with some hot sauce, of course.