This article was originally published in the August 1991 issue of SPIN.

AT 5:28 P.M. on Tuesday, July 3, 1990, officers Rodriguez and Wong of the 47th Precinct in the Bronx got the call. “MB shots . . . six rounds . . . in black Toyota Camry . . . possibly fled on Parkway . . . 241 and White near OTB.” A black male (MB) had fired six rounds at East 241st Street and White Plains Road, near the Off-Track Betting outlet, before fleeing in a Toyota toward the Bronx River Parkway.

It wasn’t a Toyota, but otherwise the radio alert matched the testimony given later by the gunman, one Ricky Walters, following his arrest. “I was driving a rent-a-car Dodge Shadow at East 241st Street and White Plains Road when I saw my cousin Mark,” Walters told the cops. “I drove home with my girlfriend, Lisa Santiago, and picked up six weapons: two .25-caliber automatic pistols, one .380, two Uzis, and one shotgun. I drove back to East 241st and White Plains, saw my cousin Mark, and shot at him about five times with my .380…. I left the scene westbound on 241st Street and got on the Bronx River Parkway going south. The police were chasing me. I tried to get off at the Allerton Avenue exit, couldn’t make the turn, and crashed.”

Walters’s testimony omits some salient points: that the corner where the shooting took place was a known drug-dealing location, where neither victim—Walters’s cousin, Mark Plummer, nor bystander Wilbert Henry—felt out of place (both were scheduled for sentencing this summer: Henry for intended sale of drugs, Plummer for drug and illegal-handgun possession). Nor does his deadpan account of the chase mention his James Brown–like weaving in and out of holiday traffic at 80 miles per hour, nor that he and his six-months pregnant girlfriend both broke a leg in the crash, nor, according to an officer at the scene, that Rick resisted arrest even as he was pried from the wreckage. Finally, he and Lisa had never gone home to get the guns, because they were in the car all along.

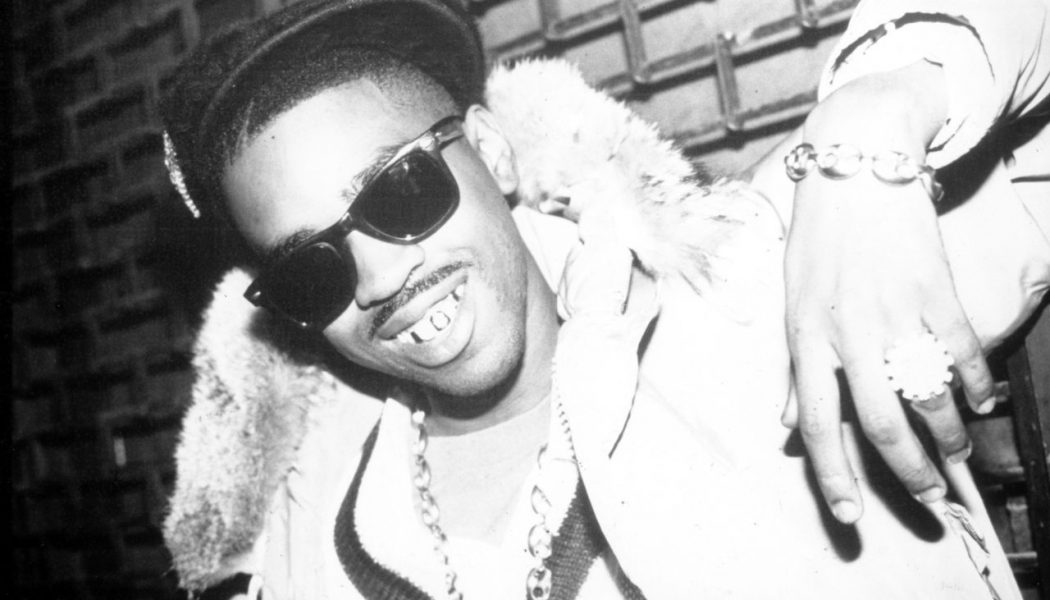

There was something else missing from the testimony. This guy Walters was not your typical gangster. In fact, he was a rap star who called himself “Slick Rick,” and had scored a hit album in 1988, The Great Adventures of Slick Rick, which sold 1.2 million copies. One song, “Children’s Story,” had even described an incident ominously similar to the not-so-great adventure Rick had just been in: “He raced up the block doing 83 / Crashed into a tree near University / Ran out of bullets and he still got static / Grabbed a pregnant lady and pulled out the automatic / Sirens sounded and he seemed astounded / Before long the boy got surrounded…. Talk about the Bronx, Rick.”

Lots of rappers talked about the Bronx or Compton, but few lived it. Then again, lots of nonrappers did live it. And though “Children’s Story” was somewhat prophetic, cops and rap insiders, especially Ricky’s former publicist Bill Adler, maintain that what happened to Ricky Walters wasn’t that unique for the Bronx. Regardless, Rick had been none too slick this time. Now he himself sat surrounded, facing a slew of charges including attempted murder. His trip through the Bronx legal system was about to begin—as were the analogies to The Bonfire of the Vanities. Except this time it was Slick Rick, the Young Black Rapper, not Sherman McCoy, the Great White Defendant, who’d get stuck in jail with an outlandish $800,000 bail. Come to think of it, the assistant D.A.’s request for higher bail gets shot down in Bonfire. This, however, was real life—not some novel.

And the only thing missing was an ambulance chaser sent by Hollywood superagent Mike Ovitz to secure movie rights.

As unlikely of a gangster as Ricky Walters was, it’s not as if the shooting of his cousin didn’t make some kind of sense. For one thing, his life had been sprinkled with incidental tragedy and casual violence almost since the day he was born to Jamaican parents in London, England, on January 14, 1965.

While still only 18 months old, Ricky got into a fight with a girl, during which some accidentally broken glass blinded his right eye. Several unsuccessful operations on his eye followed. Even so, growing up in South Wimbledon with his parents, Melton and Veronica, and his older sister, Caron, Ricky says dreamily that life “was more peaceful and slower” than in America. At school his athletic abilities extended only to “marbles,” but he was talented in other ways and indulged a knack for drawing; unlike most kids, though, he didn’t draw cartoons or graffiti but preferred “more real-life stuff.”

When Ricky was 12 his family moved to the United States and settled, ironically enough, at East 241st Street and White Plains Road in the Bronx. Kids teased him at first for his accent, and a wardrobe that was “nerdish—you know, cheap sneakers, funny colors, goofy clothes.” In time, however, he made friends with guys like his future DJ, Vance Wright, and eventually entered the La Guardia High School of Music and Arts.

Dana McCleese, now the rapper Dana Dane, was Ricky’s best friend in high school. “We could have both been B students if we went to class more,” says Dana, “but we used to go to a park with three other guys and make up rap routines.”

Musically, Ricky was already introducing McCleese to the power of storytelling as opposed to just boasting. In turn. Dana, a tough Brooklyn boy, was fascinated by Rick’s British accent and encouraged him to take advantage of it. As far as apparel went, says Dana, “We were just like twins. We had the same color Kangols, matching shoes and pants, same coat—the whole thing.” Enthralled schoolgirls often confused these Bobsey twins, who were so attached to pith helmet–style Kangol hats that Rick, Dana, and their three sidekicks became known as the Kangol Crew. Though they never cut a record, Dana insists that the crew were “legends before we even left the school.”

After school they’d play, among other things, the numbers, as Dana explains: “We was young and not working, so we’d try to make money to buy some new Pumas—’cause we always had to have new gear on at school.” Ah yes, the gear…. “Even back then Ricky had little gold chains and rings,” recalls Dana. “He got his Cazals first, and everybody wanted to rob you for them.” Cazals were the gold-plated, nonprescription eyeglasses which attracted national attention in the early ’80s when inner-city youths started killing over them. Dana says he and Ricky often got hassled, “but we knew how to get out of things—never get blocked in, keep with the posse, and don’t get separated or they might try and rush you.”

Though such violence was not unusual, Rick and Dana were hardly gangster material. “Guys used to bring guns to school and me and Ricky would be like, ‘Yo, that kid’s got a gun—that’s dope!’ At the same time, we was like, ‘Yo, we ain’t messin’ with that.’ “

After graduation, Ricky reunited with Vance Wright, who also grew up near East 241st and White Plains. “We used to chill and hang out,” Rick says today, again with just a glint of nostalgia in his eye. “He had equipment in his basement. We’d drink beer and play pool. He liked the way I was rapping—and I liked the way he was cutting.”

The duo began entering rap contests which usually ended in fights, while the prize money, sometimes as much as $1,000 (“Chump change now, but it was a lot back then,” says Vance), never got awarded. Vance soured on the scene and went to college, but it was at one of these bogus contests that Ricky caught the eye of Doug E. Fresh, a Barbados-born, Harlem-bred rapper already established as the “Original Human Beat Box.”

The result of their partnership, a 1985 single called “La-Di-Da-Di,” the B side of “The Show,” is a piece of hip hop history. With only Doug E.’s face farts as a backing track, MC Ricky D (as he was known then) jokes, sings, cries, and weaves a refreshingly melodic rap about his elaborate toilet in a Sybil-like array of voices: after taking a bubble bath, doing his nails, squeezing the Johnson’s Baby Powder, splashing on Polo cologne, and donning Gucci briefs, he hits the streets and breaks the heart of a woman twice his age. If Barry Manilow were reincarnated as a rapper, this is probably what he’d sound like.

Over five hundred thousand copies later, and with a Madison Square Garden show under their belts, these two were not only pioneers—they were stars. The only hitch was that Doug E. wouldn’t pay Ricky his fair share, or at least that’s what Ricky said at the time. Nowadays Ricky puts their breakup down to a clash of ideas; either way, it was too bad, because another of their songs, “Treat Her Like a Prostitute,” was fast becoming an underground favorite. It would have to stay that way for three years.

There is a lot of speculation but little fact as to what happened in the three years between “La-Di-Da-Di,” and the release of Ricky’s debut album on Def Jam. Only one thing is certain: Rick’s image as an eccentric mushroomed. Some said he’d been on the pipe and was now in rehab. Or that he’d been stabbed while he was in Harlem with Doug E. That he’d smoked some bad dust. That someone had spiked his drink. The most persistent story of all was that Def Jam president Russell Simmons had him sprung from a mental hospital to make the LP.

“That’s not true,” Simmons snorts, adding, “I didn’t fuck with him.” (At least one rap insider, nevertheless, still insists otherwise.) Ricky himself denies the rumors, saying that he just didn’t want to put out anything “wack” and that it took a while to get right. Whatever the case, once he started working on his first album, the recording sessions were, as they say, stormy. “He fired everybody,” Simmons says. “Rick Rubin, Sam Sever, me! I was the first one! We made something, and it was dope…. He hated it.”

Only Public Enemy producer Hank Shocklee was able to work with the stubborn rapper. Ricky told me he got along with Shocklee, but he told another reporter Hank was “useless” to him. For his part, Shocklee gives a familiar take on Ricky: “He’s a genius, almost a Hendrix personality.”

Indeed, The Great Adventures of Slick Rick had the stuff of genius. “Treat Her Like a Prostitute” predated 2 Live Crew’s overt sexism; “Children’s Story” anticipated Ice Cube’s gangster tales. Ricky’s rapid-fire clarity inspired Young M.C., while his schizophrenic breaks into Diana Ross oldies and the Davy Crockett TV theme created an unpredictable character who paved the way for every calculated caricature since, from Kwame the Boy Genius to Humpty Hump.

Fans responded accordingly, the album went platinum, and now that he was a star, Ricky wanted to look like one. “After selling a couple hundred thousand records,” says Russell Simmons, “an artist will come in and ask for a car and some gold. We always say, ‘Why don’t you buy a stage set?’” Ricky took the cars—specifically a red Mercedes sports coupe and red Nissan Pathfinder. He also took the gold, eventually $60,000 worth, mostly in the form of thick rope necklaces.

So while Afrocentrics rediscovered the dashiki, and would-be gangsters cocked their Raiders caps, Ricky stood out—neither old school nor new school, but a little of both. The gold was B-boy, but he wore no sneakers or sports gear. The suede Bally Aden shoes, cardigan sweaters, suits and fur-collared charcoal trench coat were distinguished like De La Soul, but more yuppie than hippie. With his eye patch, he looked quite the star. Soon he’d be acting like one as well.

Rick at the height of his popularity was a piece of work. His nickname was “The Ruler”; his favorite phrase was “I’ll crush you.” He called people “crumbs,” and he’d do things like purposely barge into you at clubs. Onstage he’d dis everybody from his dancers to Russell Simmons. Reportedly, he “didn’t have a lot of friends among rappers.” (When I saw Rick with Chuck D recently, they hugged—but they were like two society matrons. Even Chuck, the loudmouth clad in sweat shorts and Bulls jersey, was disarmed by the distant dandy.)

Apparently, Rick would fly around town in a Mercedes littered with the bottles of Moet champagne that he guzzled like most rappers quaff “40s”; according to one observer, he was literally cruisin’ for a bruisin’. Predictably, the tailspin only enhanced his reputation and increased his draw. The teen ‘zine Rap Masters giggled that “Slick Rick’s antics on- and offstage made the year amusing.” They also ran a “Win Dinner With Slick Rick:” Contest; which, due to unexpected events, nobody ever won.

It was his mother, Veronica who suggested that Ricky hire his cousin Mark as a security guard for the summer ’89 tour with LL. Cool J, Big Daddy Kane, and others. Veronica was Ricky’s tour manager, and noticed that Mark appeared to be making even more money than Ricky—though at what it wasn’t quite clear. Nevertheless, he was to provide muscle so Ricky wouldn’t have to carry a gun—something which Ricky, by now, was doing in the “hectic” wake of his first album. Ironically, security on that tour may have lapsed when Ricky and Kane (who were friends) had a reported run-in; Ricky allegedly pulled a gun on Kane backstage, but today he says it was merely a verbal dispute over billing order.

Meanwhile, Ricky says Mark was receiving $500 a week and wanted more. Rick claims he gave Mark $3,000, a van, and told him to chill until his new album came out. (Most of Rick’s Adventures royalties were by now tied up in real estate.) Ricky further alleges that Mark, not satisfied, pressured Veronica into giving him some cash. Mark busted Ricky’s chops in other ways. He wouldn’t register the van in his own name, and it accumulated tickets in Rick’s name. Ultimately, says Rick, “He played like he had nothing against me, and then he’d have one of his friends rob me.”

Which is how Rick describes the events of April 20 last year, when his Pathfinder was shot through with at least 20 bullets outside the Castle, a rough Bronx dub where rappers go to see and be seen. “I’m not sure,” says Rick about the attack in which he was grazed in the back while two friends escaped with no serious injuries. “It happened so fast. But it was him and his people.”

Mark then allegedly resumed his “extortion.” “This is what people like him do for a living,” says Rick, “they rob drug dealers—big-time dealers.”

Rick related what happened next during his July 3 testimony to the cops. “About one month ago … I was walking toward the front door of my house when an unidentified black male ran up to me with a gun in his hand. I was able to get into my apartment first. This guy started kicking my front door; I fired one shot through the door to scare him. This male left and about thirty seconds later, I heard a male voice—it sounded like my stepfather’s voice. He said, ‘Ricky, open the door. “

According to the police report, it was actually Mark impersonating his stepfather’s voice. Ricky didn’t fall for the ruse, so Mark left and a few minutes later allegedly called Ricky and threatened to kill him. The next day Mark told Ricky in person he was going to kill both Ricky and his mother. Apparently that did it. As Ricky says, “Mess with a nigga’s moms, and …”

Rick explains what he did next on the grounds of Mark’s street reputation: “He’s murdered people but he’s never been caught.” (Detectives from the 47th Precinct state that Mark Plummer is not and has never been a murder suspect.)

According to Ricky, it was about a month later during the early evening of July 3 when he drove by the corner of White Plains and 241st. In “Children’s Story” the “Kid starts to figure / I’ll do years if I pull this trigger,” but Ricky slowed down the car and took aim.

After the crash Ricky was taken to the Bronx Municipal Hospital, where he stayed under round-the-clock security for a couple of weeks. Arraigned on July 12, he was sent to Manhattan Detention Complex, and he cooled his heels there from July 16 until February 28 while waiting for the $800,000 bail to be posted. Respectful of his celebrity and sympathetic to the severity of his bail, the inmates left him alone, giving Ricky time to rhyme. Says Vance, “He’d be calling me, telling me to get this and that beat. I’d call him back and play it, and he’d kick it in his head to make sure they were flowin’. That’s how we did a lot of the new album.”

Productive as he was, Ricky still faced two counts of attempted murder, two for assault, and six illegal-weapons charges. But basically it came down to this: The minimum in New York State for attempted murder is two to six years, the max is eight and a third to twenty-five. According to Peter Gersten, one of Ricky’s lawyers, Judge Gerald Sheindlin “made us an offer we couldn’t refuse.” In return for pleading guilty, Ricky was guaranteed no more than three and a third to ten—minus the eight months time already served.

Eventually Def Jam posted bail, and after pleading guilty on March 22, Ricky was given until June 6 to do some recording. Then, flanked by bodyguards and holed up in top-secret locations like Manhattan’s Chung King Recording Studios, Ricky quickly completed two albums and five videos. The material, though not stunning, is still uniquely Ricky, a mixture of melody and melancholy. “Aw, Rick’s sad again,” the beginning of one song warns; “I’m feeling sad and blue,” the chorus of the first single, “Shouldn’t Have Done That” croons.

This time Rick and Vance produced the material themselves. When outside producers like Prince Paul and Marley Marl contributed, there was no static. Rick’s newfound amiability prompts Russell Simmons to claim that Rick “is already rehabilitated.” Rick hasn’t been seen drinking, he’s closer to his family, and he’s intent on staying with his girlfriend Lisa, who gave birth to their son, Rick, just over a year ago. Rick, Sr., is even playing the good father, having already “trucked” the toddler with gold chains. But while little Rick’s dad insists that “no one should go to jail for protecting their legally earned property,” and that he’s “a good guy who got fucked,” he had fought the law. And as usual, the law won.

At the sentencing on June 6, another of Rick’s lawyers, James Gagliardi, lambasted the district attorney for being “unfair” and “inflexible.” He compared Rick, who stood with head bowed, to boxer Jack Johnson and pointed to some volunteer work he’d done for the Department of Public Safety. Judge Sheindlin appreciated Rick’s contrition but noted that “people look up to you and they have to know that if you do wrong things, terrible things will happen to you.” With that, he sentenced Rick, as promised, to three and a third to ten years. Rick was cuffed and, in his purple suit and blue Ballys, led away. At the last moment he looked back at his family and friends. Outside the courtroom his mother Veronica finally broke down. As you read this, his new album, The Ruler’s Back, should be in the stores, and Rick should be in an upstate prison.

So what’s the real date? Is Ricky Walters, as he says, a good guy threatened by a thug cousin? Or is there something else to this case? A detective who investigated the April strafing of Ricky’s Pathfinder said his gut instincts told him it was drug-related. But as rap promoter Mickey Bentsen points out, “Police always assume that if they’re black and rich it must be drugs.” Bentsen adds cryptically that one could even say “Ricky did the police a favor by trying to nail that guy and defend himself. The cops are gonna do it themselves in a couple of years and get patted on the back for it.

Regardless of whether or not justice is (color) blind, there is something else to this case, but it doesn’t involve drugs—it involves murder. Remember Rick’s account of the incident outside his home, when he fired a shot through the door to scare off the would-be burglar? The police later investigated whether Rick may have hit the person—or even killed him.

According to sources in the 47th Precinct, a man named Cornell Sutherland was found dead a block and a half from Ricky’s house on DeRiemer Avenue on Thursday morning, April 19, 1990. Interestingly, the next night, April 20, was when Ricky’s car got shot up outside the Castle—an incident which heretofore was viewed as unprovoked. Perhaps that’s why Rick told police that the robbery attempt outside his door was in June, not April. And perhaps Mark wasn’t joking when he allegedly threatened to kill Rick and his mother. After all, Rick’s lawyer James Gagliardi said at the sentencing that Rick was “paranoid” and “terrorized” because the word on the street was that Mark would kill Rick if he saw him. Rick, in desperation, figured he’d get to Mark first, and apparently did. “That’s the code up in the Bronx,” Bill Adler notes. “If you get ricked [victimized] and don’t do anything, you’re a sucker.”

The cops, however, didn’t suspect Ricky of Sutherland’s murder at the time. It was only after his arrest in July—when he told them about shooting through the door—that they started investigating. So why wasn’t Ricky prosecuted? Investigators from the 47th say they found no evidence to match the bullet in Sutherland’s body to the guns later found in Rick’s car. They went to Ricky’s house looking for clues, but the shot-through door had been replaced. It remains an unsolved homicide.

Funny thing is, Ricky doesn’t look like a murderer. When I interviewed him, the only thing he looked like was a million bucks. He was resplendent in yellow from head to toe. Not only were the oversized Kangol beret, the window-pane checked suit, the socks and the shirt all yellow—but the Bally kicks were too. Rounding out the ensemble were the nose stud, diamond-encrusted front tooth, bracelets, rope necklaces, medallions embossed with a lion, a scorpion, a Libra sign, and finally, as Syd Barrett once said, “lots of rings and things to make it look good.” Somehow the whole shebang actually worked. The $60,000 worth of gold around Rick’s neck dangled and jangled, but it never got in the way.

“You got to have a lot of balls and be pretty strong to wear that much gold,” says Russell Simmons. “On anybody else it would be too much, but that just shows how different and special Ricky is.”

Different and special. Lots of people seemed to coddle Ricky. You’d think he was either retarded or some kind of boy king. A truly funky King Tut. And though I told Ricky not to worry, when he ended our conversation by saying, “Don’t make me look bad,” I had to be careful not to catch Mailer’s Syndrome and paint the man as a Jack Henry Abbott (the criminal cause célèbre who killed after stormin’ Norman helped get him released). For one thing, there were the contradictions: Ricky has said he “was never on the gold tip” before the first album; Dana said he was always into it since high school. Ricky says his cousin was the first guy who tried to rob him; Dana again says they’d dealt with that shit since high school. Ricky said he didn’t tell the cops about the robbery attempt outside his front door because he thought they’d bust him for his guns, but the way he put it to me was, “What good’s a yellow piece of paper [restraining order] when you’re dead?”

These erratic accounts only serve to illuminate the different Ricks: There was Ricky, the shy, sensitive, easily heartbroken mama’s boy who scrubbed behind his ears, the only rapper to ever pout in profile like Michael Stipe. Then there was Rick, the big star and would-be Jamaican baddie obsessed with gold and guns. In his cardigan Ricky looked almost the professor. Add the eye patch and you had a pirate.

The result of these two personalities, Ricky and Rick, rubbing up against each other was predictable enough to childhood friend Dana Dane. “I always knew something was gonna happen,” says Dane. “I just didn’t know what.”

Most people interviewed for this piece agree that Rick was “unbalanced” and a “genius.” As Russell Simmons put it, “A lot of great poets have a background and attitude that’s normal, whereas Ricky is a true artist—he’s kind of bugged, like my man Miles Davis.”

Then again, Ricky didn’t plead insanity, he pled guilty. So isn’t it a cop-out to say that this Hendrix, this Miles Davis of rap, was crazy? Not really. Of course, anyone who attempts murder has already crossed the line, but Rick isn’t the archetypal “Crazy Nigger” in the Huey Newton mold. Rather, he’s crazy like a fox. “I was never shooting people for no reason,” he explains. And in his mind it all made perfect sense.