More than other recent years, in 2021 the tech industry focused a great deal of its energy on a single question: who will build and own the next generation of the internet?

In one corner you have the scrappy upstarts eager to topple the existing world order and rebuild it from scratch on the blockchain. These companies give their effort the aspirational name “Web3.”

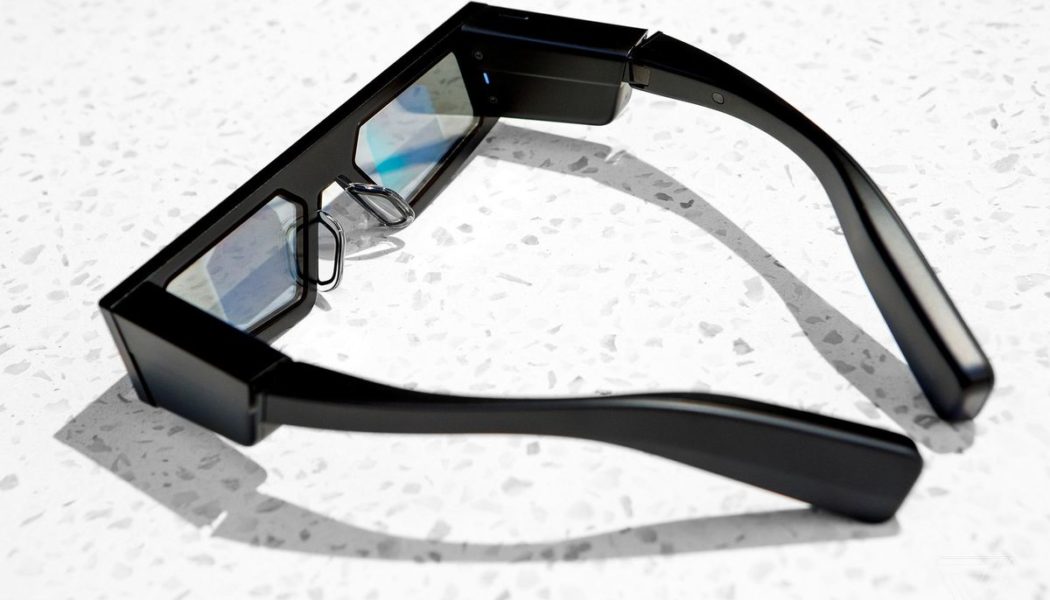

In the other corner you have the existing tech platforms, who envision the next generation of the internet as a slightly more interoperable version of the existing web. What will set it apart is new hardware: augmented reality glasses and virtual reality helmets that will bring us together in a series of linked experiences that occupy an ever-increasing share of our waking hours. Platforms have taken to calling this “the metaverse.”

Web3 and the metaverse will surely intersect along the way — Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg has said he imagines people bringing non-fungible tokens along with them as they traverse the company’s virtual worlds. But while crypto-based platforms are still mostly in their earliest stages, the battle for the metaverse already has at least a half-dozen established companies investing billions of dollars in realizing it.

Today, let’s talk about one that strangely flies a little under the radar — and is taking a more straightforward path. While other companies are painting grand visions of the metaverse via press interviews and op-eds, Snap has been quietly focused on two of the ideas that can actually bring it into existence: steadily improving its hardware every year or so, and attracting developers by giving away that hardware and offering them ways to profit from it.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23060781/alopez_211129_4909_0010.jpg)

The core function of AR glasses is to project images in front of your face, turning your field of vision into a virtual computer screen on which you can receive messages, play games, and interact with digital or real-world objects for educational or commercial purposes. Most platform executives agree that this would be a good and useful thing, and that lots of people would buy the hardware that makes it possible.

The problem is that the tech isn’t ready: creating high-resolution projections using a device that fits on your face, has good battery life, and costs a reasonable price, is far beyond the ability of today’s platforms.

Surveying the AR landscape this week, The Wall Street Journal predicted that someday high-tech glasses will become Apple’s successor to the iPhone. It looked at similar efforts from Facebook, Microsoft, and the lesser-known Vuzix, among others. And to Snap, which made the first major set of high-tech glasses when it released Spectacles in 2016, the Journal devoted just a single sentence: “Snapchat parent Snap earlier this year added AR functions to the latest version of its Spectacles smart-glasses, which are so far available only for developers.”

Indeed, when they were announced in May, Spectacles became the first pair of the company’s glasses I didn’t get to try myself. Instead, the company seeded them with a handful of developers who create AR effects, games, and utilities and gave them a few months to build.

And then, one day last week, the company invited me to a rented backyard in San Francisco’s Castro District to see the results.

Within a few minutes of wearing the glasses, two things became clear to me. One is that these are very much a product for developers rather than consumers. The chonky frames, 30-minute battery, and presumably high price would limit their appeal to all but the most hardcore futurists.

At the same time, my morning with Spectacles was enough to convince me that AR glasses have a promising future, and are likely to print money for the companies that manage to perfect them.

It started with a donut. Sitting around a table with some Snap executives, I was introduced to Brielle Garcia, a full-time AR creator who is part of the company’s Ghost program for up-and-coming developers. Garcia has made dozens of AR effects for Snapchat — the company calls them “lenses” — and one such idea came to her while eating at a restaurant during COVID. Like many eateries, this one had begun telling customers to scan codes with their phones to access the menu. Garcia thought it would look better in AR.

Using Snap’s Lens Studio software, she mocked up a menu that displays items in three dimensions sitting virtually on your table. When I opened it up using Spectacles, I waved my hands to advance through the virtual goods: a burger, a sushi roll, a piece of pie. The donut looked realistic enough that I developed slight hunger pangs looking at it. Compared to a QR code menu on my phone, Garcia’s AR project was meaningfully better. And I felt that way despite the relatively low resolution of the text, at least compared to what you might see on a current-generation smartphone.

The Snap team had other tricks to show off. In one game, a zombie chased me around the yard. (Alex Heath, who got a similar demo at The Verge, posted a video of his zombie chase that gives you the idea.) In another, I hung virtual Christmas lights on the trees.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23060786/alopez_211129_4909_0015.jpg)

The flaws are all readily apparent. The biggest among them is the relatively small field of view that Spectacles can produce using its current technology. When you don the glasses, you might assume that you’ll be able to see a digital overlay that covers everything you see. Instead, it’s a relatively small box at the center of your vision. As a result, I was constantly moving my ahead to attempt to “place” the digital effect back in the box where I could see it.

In some cases, as with Garcia’s menu, objects were relatively small and slow-moving, and this was fine. In others, particularly the zombie chase, the field of view was so small that I found the game all but unplayable.

That said, the state of the art is still further along than I expected when I first sat down with the glasses. For my final demo of the day, I used Spectacles to project a toy dinosaur on the table we were all sitting at. It appeared as a perfect hologram, contained neatly within the glasses’ field of view — the sort of thing that would delight any child to whom you showed it.

A small thing today, but one that points to a big future.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23060793/alopez_211129_4909_0022.jpg)

Snap faces a lot of competition as it works to turn today’s Spectacles into the iPhone of the future. Apple is at work on its own headset, which will combine AR and VR, and will reportedly debut it next year. Meta is working to launch AR glasses next year as well. And Microsoft just signed a deal with Samsung to collaborate on a future generation of its HoloLens headset that will presumably be aimed at consumers. (It’s not expected until 2024.)

Meanwhile, more software-oriented efforts from Roblox, Epic Games, and Niantic are all afoot — and will likely lead to hardware projects of their own down the road. (Niantic has already commissioned a reference design.)

But one thing about Snap, as co-founder Bobby Murphy told me this week, is that the company has been working on this initiative for many years — predating much of its current competitive set.

“We’ve been incredibly invested and interested in an AR future for for many, many years now,” Murphy told me ahead of its LensFest developer event, which runs through Thursday. “The ability to perceive and render digital experiences directly into the world really aligns to how we as humans naturally operate.”

To date, Snap has signed up 250,000 people to create more than 2.5 million AR effects. More than 300 of those people have gotten 1 billion or more views on their Snapchat lenses, the company says. Snapchat lenses are viewed 6 billion times per day.

Of course, the majority of those are purely for entertainment: making your face look younger, or prettier, or otherwise distorted to send snaps to your friends, or to place a digital dancing hot dog in the environment around you. But Snap has started to layer in other sorts of experiences, like a “scan” feature that lets you use the Snapchat camera to identify trees — or, more importantly, from a revenue perspective — shopping opportunities.

It turns out that all those funny-face lenses trained a generation of users that a screen can itself be a window into real-world experiences, whether on a smartphone or a pair of glasses.

“That’s actually been a very helpful starting point for us to start to push into kind of a much wider variety of use cases,” Murphy told me.

One thing you won’t catch Murphy doing much is talking about the metaverse. While Snap’s ambitions arguably fit under that umbrella, the company seems confident enough in its existing vision not to adopt the buzzwords of the moment. At the same time, Murphy says the recent acceleration in development around AR is real.

“It’s not that there’s been a leap in technology, but I think we are starting to see a broader emergence of use cases for which AR is maybe escaping the novelty sphere, and actually driving real value for for companies and for creators,” he said.

There’s no reliable timeline for when that next leap will occur — and when hundreds of millions of people will begin wearing their AR glasses in the way many assume they someday will. But using the latest version of Spectacles, I find myself having trouble believing that someone won’t get there eventually — and maybe sooner than a lot of people think.

“The way that we’re looking at our opportunity in the future, it’s really around developing this kind of singular, holistic platform,” Murphy said. “In which you as an AR creator can make something really compelling, and get that in front of people — through Snapchat, through CameraKit, through Spectacles — and then build a career or build a business through that kind of path.”

Winning over developers doesn’t guarantee that any particular company will win the mixed-reality future. But no one can win without them, either. For the moment, Snap has more than its share of enthusiastic creators. And together, they just might make the metaverse an actual reality — even if the company never calls it that.