On August 23rd, 2020, police shot Jacob Blake four times in the back in Kenosha, Wisconsin — and within hours, the streets were full of protestors. The National Guard was activated the following morning, and the next week would see as many as 40 buildings destroyed, as well as two people shot dead by a counter-protestor before order was restored.

But while the events of that week have been closely watched, many of the law enforcement tactics used to respond to those protests are only now coming to light. A series of six newly unsealed warrants (1 2 3 4 5 6), some previously reported by Forbes, show a persistent effort to use Google’s location services to identify Android users in the vicinity of arson incidents.

Issued in quick succession on September 3rd, the warrants came from a team of 50 arson investigators from the bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, deployed to Kenosha to prosecute property damage cases connected to the protests. Using the warrants, The agents targeted seven different geographical zones, asking to identify anyone located within that area during a span that could stretch as long as two hours. The result was a kind of location dragnet, spread over some of the busiest times and locations in the first days of the protest.

Searching location data for users in a particular area — called a geofence warrant — is a controversial practice that has become widespread in recent years. In one incident in 2020, the data implicated a bicyclist in the burglary of a home he often rode by. But while the technique is always controversial, it’s particularly alarming when it’s used in conjunction with a mass protest event, inevitably sweeping up innocent civilians alongside suspected arsonists.

Jennifer Lynch, who leads the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Street Level Surveillance project, says the fact that police were able to obtain the six warrants with little pushback from the courts shows how dangerous geofence warrants can be. “We know there were hundreds if not thousands of people in the area who were engaged in lawful protest activity,” says Lynch. “It’s unconstitutionally broad. There’s no probable cause alleged in any of the warrants that would support a search encompassing so many people.”

Most concerning to privacy advocates, the warrants contain no acknowledgement of the risks of incidental data collection or provisions that would limit the privacy risks of such a request. “When you have an investigation that necessarily involves the collection of information on protests,” says Brett Kaufman, an attorney with the American Civil Liberty Union’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, “protections need to be in place to both limit collection on the front end and establish the destruction of incidental data afterwards. Otherwise, you’re just giving the government carte blanche.”

The six geofence warrants issued after the Kenosha protests vary widely in their specificity. The most particular request draws on video footage and an eyewitness account of an attempted arson at a TCF Bank just southwest of the city center. That evidence allowed police to narrow the timeframe to a 22-minute period when someone on the north side of the bank broke its windows and hurled in flaming objects.

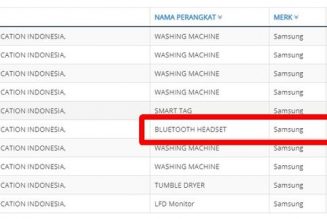

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22814500/Screen_Shot_2021_08_30_at_8.47.51_AM.png)

Other warrants are far more general. A different warrant looks at a suspected arson of the Kenosha Public Library, based on lighter fluid and rags that were discovered in a northeast window well alongside minimal fire damage. Without direct witnesses to the fire, police set a two-hour window and a geofence covering the middle third of the downtown’s largest public park space. It was a significant span of time on the busiest night of the protest in an area that provided a natural meeting place for anyone who had taken to the streets that night.

The near-certainty of incidental collection is particularly alarming for Lynch. “What’s not provided in the warrants is any discussion of how many people were in that geographic area at the time covered by the warrant,” she says. “Those people were not connected to the arsons under investigation and there’s absolutely no reason law enforcement should be able to get access to their location information.”

Notably, this isn’t the first time the technique has been used in the wake of a police protest. In May 2020, Minneapolis police used a similar technique to investigate the vandalization of an Autozone store during protests sparked by the murder of George Floyd.

While many devices collect location data, Google has become a particular target for geofence warrants because of its data retention practices. iOS stores location data in an anonymized and ephemeral way that makes it less accessible to court orders. Google has been reluctant to adopt such a system for Android, in part because of the data’s value for targeted advertising.

The last pages of the warrants show a particular procedure put in place by Google in an effort to address the privacy risks of the system, although much of the process would take place outside of the oversight of the court. Under the system, Google first produces a series of location points, identified with timestamps and unique IDs but no further identifiable information. Once presented with that list, law enforcement “may, at its discretion, identify a subset of the devices,” the warrant reads.

But while Google’s system could potentially narrow the scope of the warrant, there’s no guidance for how the requests would be narrowed in practice. Most importantly, there’s no mechanism to stop law enforcement from routinely asking to identify every device ID provided, and Google would have no grounds to resist such a request once the warrant has been issued.

As a result, critics of geofence warrants see the system as offering little meaningful protection. “It’s a little preposterous to have Google doing its own assessment of what the constitution requires,” says Kaufman. “The rules that govern this kind of data do not come from a private company. They come from the constitution.”

Kaufman sees the problem as particularly urgent given the rapid growth of geofence warrant requests. Google served more than 11,000 geofence warrants in 2020, according to a transparency report released by the company earlier this month, the vast majority coming from state and local jurisdictions.

“It really is an alarming development that this has expanded so rapidly,” says Kaufman. “The courts need to start paying particular attention to it.”

Correction: A previous version of this piece said Jacob Blake was shot during a traffic stop. In fact, police were responding to a 911 call. The Verge regrets the error.