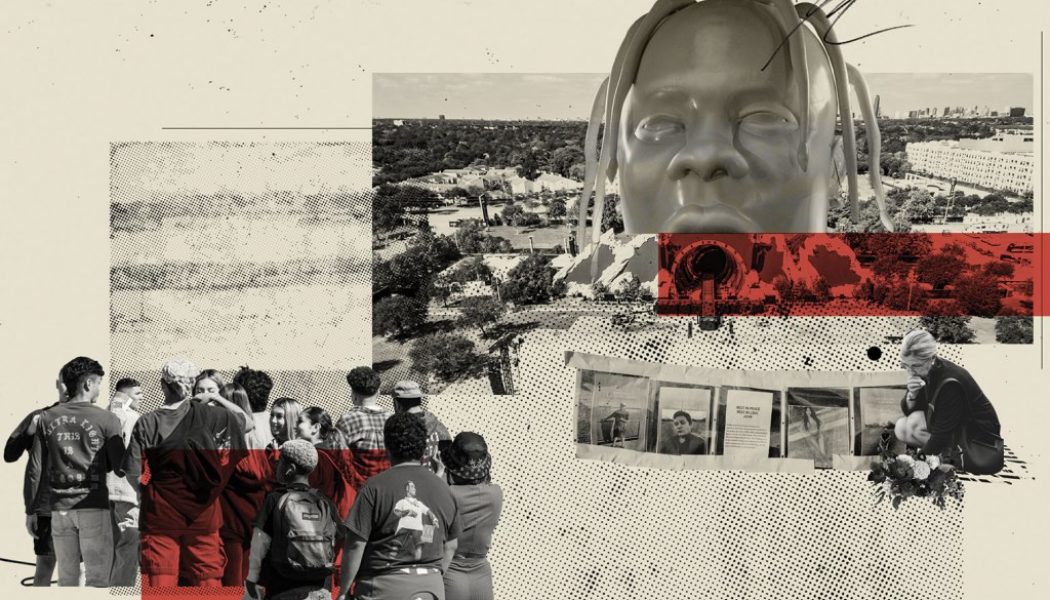

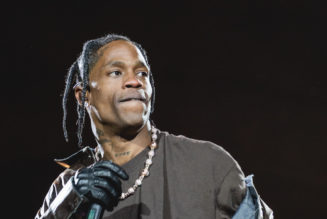

Travis Scott encourages his concert audiences to “rage,” so his Astroworld festival, which this year drew 50,000 fans on Nov. 5 to NRG Park in Houston, needs to be organized in a way that keeps attendees safe. But ScoreMore Shows, which produces and promotes the event, set it up in a way that several concert business sources say may have inadvertently contributed to the crowd surge that resulted in 10 deaths and hundreds of injuries, and that parent company Live Nation rarely exercises the kind of oversight over events organized by its subsidiaries that might have flagged these problems before it was too late.

The hands-off approach is by design. Live Nation CEO Michael Rapino runs the company with a decentralized management strategy that encourages promoters it acquires, such as ScoreMore, to run as independent units, each responsible for its own revenue and expenses. That encourages the kind of aggressive booking strategies that keep Live Nation’s event pipeline full of shows that generate Ticketmaster fees, sponsorships and other revenue. But it also means that the expertise of its most experienced personnel isn’t always shared internally.

Rapino “views promoters as entrepreneurs and doesn’t see any net gain in forcing a one-size-fits-all approach,” explained a former Live Nation executive. “The dozens of regional and independent promoters purchased by Live Nation operate more like a federation than a corporation with its strength drawn from its alignment.”

In the wake of the Nov. 5 tragedy, Live Nation and ScoreMore — an Austin-based company that the mega-promoter acquired in 2018 and now essentially operates as a subsidiary — have been criticized for allegedly cutting corners on Astroworld, but they don’t actually appear to have cut costs. In fact, the stage created just for Scott’s performance at the festival cost $5 million, according to ScoreMore. The promoter also hired over 500 police officers, plus another 700 security guards for the festival — more than is typical for an event of that size. At least some of the fault lies in the setup of the event, however, and though Live Nation has a wealth of experts in its ranks who might have spotted potential problems, the company’s various divisions operate with considerable independence.

Sometimes that leaves them on their own. On the night of Nov. 5, ScoreMore co-founder/CEO Sascha Stone Guttfreund was home with COVID-19, according to numerous sources, and as Astroworld descended into chaos, the responsibility for whether to stop the show mainly fell to Brad Wavra, a veteran touring executive who industry sources say doesn’t have much experience running festivals. (Wavra and ScoreMore didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment, and Live Nation declined to comment on the events at Astroworld, beyond public statements of sympathy.)

Astroworld presented acts on two stages: one for the other artists on the lineup and one for Scott, with the viewing area in front of Scott’s divided into four sections by four barricades. One ran perpendicular to the stage, bisecting the audience; the others were set up parallel to the stage: one just in front of it, one about halfway through the main viewing area and one in front of the video cameras at the end of that area. Such setups, which are common at general admission festivals, are meant to protect fans close to the stage by limiting the number of people who can push forward into them.

Unlike most festivals with potentially aggressive crowds, however, the area in front of Scott’s stage didn’t have barriers on its left and right sides. His stage was 200 feet long — over three times the length of the main stage at Coachella — and since almost all of the action took place in the center, concertgoers swarmed into the main viewing area from both sides, then pushed toward the middle, according to numerous accounts. As the crowd surge worsened, fans ended up surrounded on three sides by barriers intended to protect them. Even before Scott got onstage, the crowd was so tightly packed that some fans began jumping over the barricades to escape a situation some said already felt dangerous.

Then it got worse. Most festivals schedule performances by major artists to overlap in order to spread out the audience, but Scott was scheduled to perform after all the other acts had finished. And as an onscreen countdown clock ticked off the minutes until his set began at 9:06 p.m., what should have been a steady move toward the viewing areas in front of his stage became a rush. Fans poured in from the open sides of the four main viewing areas, and the barriers on the other sides left no way out. Some fans were lifted into the photo pit to escape the crush. By 9:30 p.m., the Houston Fire Department heard radio calls about CPR being administered to concertgoers who had been caught in the surge, and an ambulance was driving through the crowd. Scott paused his performance, then told the crowd he wanted to “hear the ground shake.” Seven minutes later, Houston Fire Chief Samuel Peña declared a “mass casualty incident.”

It’s possible that an experienced concert business executive with a background in crowd management would have flagged that Astroworld’s setup had the potential to exacerbate crowding problems. It’s not clear whether such a person ever saw the design plans, however. The festival’s plan for backup medical care could have been flagged as well. Astroworld hired Paradocs, a private company that handles medical care at many festivals and big events, and the company had a plan to get backup from the fire department if it encountered a situation for which it didn’t have enough Paradocs staffers or supplies. But the company gave the fire department a list of staffers’ mobile phone numbers instead of one of its radios, and Peña said at a press conference that staffers were left trying to call for backup with mobile phones — which can be notoriously unreliable amid festival crowds.

How did that happen? With a value that exceeds $26 billion, Live Nation has a wealth of resources, as well as access to considerable expertise from promoters at other companies it has bought over the years, including Insomniac and C3 Presents, two of the leading festival promoters in the world. Like ScoreMore, C3 is based in Austin, and it produces and promotes Lollapalooza, Austin City Limits and, as of 2020, Bonnaroo. Under Live Nation’s normal operating procedure, though, sources say, ScoreMore would not have had to speak to anyone at C3 about its plans for Astroworld.

“It’s very decentralized,” Rapino said about the company during a 2017 interview at Canadian Music Week. “What I love about what we do is the Insomniac guys or the festival guys or the artist-management division have all these different businesses that we’re partners in.” On Live Nation’s website, one of its pitches to prospective employees is, “We live for decentralization.” “We don’t believe in bureaucracy, and we don’t mandate synergy,” the site reads. “We keep our corporate teams small because we trust that our decentralized divisions know how to make the best decisions for their businesses in real time.”

With Stone Guttfreund sick, on-the-ground responsibility mainly fell to Wavra, whom Stone Guttfreund helped sign Scott to a touring and festival deal with Live Nation in 2018, just after the company bought ScoreMore. That meant the decision to stop the concert if it became unsafe would fall to him, whether Scott wanted that or not. This had the potential to put Wavra in a tough position because part of his job involves retaining Scott as a touring artist for Live Nation.

Wavra was the only full-time Live Nation executive at Astroworld listed on the “event operation plan.” The festival management team on the ground consisted almost entirely of contractors. The Columbus, Ohio, company B3 Risk Solutions, often hired by Live Nation promoter Insomniac to work on EDM events including Electric Daisy Carnival, did event and strategy planning. (B3 founder Seyth Boardman often works with Live Nation, but he was listed in the event plan as a contractor.) Veteran Houston concert promoter Brent Silberstein was hired as a freelance operations manager, and Joe Stallone, who has done legal work for ScoreMore, is listed in the plan as one of the event’s seven managers.

BWG Live, a Southern California production company co-founded by former Goldenvoice producers Leo Nitzberg and Meg Dieters, handled the production work, designing the stage and managing the technical aspects of the performance. According to the event plan, a BWG employee, Emily Ockenden, was listed as the first person to be contacted by emergency officials. (Ockenden would not comment.) There is no evidence that any of these managers did anything wrong. But several executives at Live Nation have more experience running general admission festivals.

Moments after Astroworld was declared a mass-casualty incident, Houston Police Chief Troy Finner spoke with organizers at the event, and Finner said at a Nov. 8 press conference that they agreed that the show would continue for another half hour, then end at 10:10 p.m. Later on Nov. 8, a Houston police representative told Billboard that the decision of when to stop the show was made by Finner, who chose not to end it earlier out of concern that this might lead to a riot.

Then, at a Nov. 10 press conference — after images emerged of Houston police officers standing in the photo pit taking pictures of Scott performing with Drake — Finner said his previous comments had been misunderstood and that he had told the promoters to shut down the show. He said that they, not he, had the power to end the concert because the festival was held on county property. Finner added that he didn’t think the matter warranted an independent investigation.

Neither Wavra nor anyone else from ScoreMore or Live Nation have said anything about how the conversation with Finner went, and it’s still unclear who made the decision to keep the show going after it was declared a mass-casualty incident, or the decision on when to stop it. That information, when it emerges, will serve to frame a more important question: whether letting the show continue may have worsened the tragedy.

The other question, which can only be answered in court, in one of the more than 170 lawsuits filed against various entities involved in organizing Astroworld, is who has legal responsibility for what happened. And regardless of the way Live Nation is set up to operate, one of the most likely answers points to the company.