Laura Stevenson is sitting in her cluttered bedroom, struggling to think of the right word to describe her songwriting process. It’s on the tip of her tongue. “I don’t have, I don’t have…” she says over Zoom as she mentally rifles through her vocabulary. Her eyes scan the baby bottles and children’s toys scattered around the room. “See, this is what happens to your brain when you don’t sleep for an entire year,” she laughs. Finally, the word she was looking for strikes her. “Discipline! I don’t have discipline.”

Stevenson is at home in the Hudson Valley in New York, and has a rare hour to herself. Her in-laws have taken her one-year-old daughter off her hands for the afternoon, and Mike Campbell, her husband and bandmate, is in the Florida Keys on “a fuckabout,” as she puts it, relaxing and enjoying a much needed mental break. After the two years the couple have endured, he deserves the time to himself, she says. They both do.

It started in 2018, when Stevenson was wrapping up work on her fifth album, The Big Freeze. That’s when she got the call. A loved one was in dire need of her help processing a sudden traumatic experience, one whose details Stevenson prefers to keep private due to its sensitive nature. It was the proceeding months of heartbreak, anger, and uncertainty that served as the inspiration behind her new album, Laura Stevenson.

It’s rare for Stevenson to be so guarded about her music. She’s historically been extremely candid about the personal challenges that have inspired her songs, perhaps to a fault. She has written and spoken about depression, body issues, and domestic abuse. When she released The Big Freeze’s standout track, “Dermatillomania,” she penned a lengthy accompanying essay detailing her longtime struggles with the titular disorder which causes her to compulsively pick at her skin until it scars. “I’m such a people-pleaser,” she says. “Anyone I do an interview with, even complete strangers, I want to be their friend. So I’ve always been forthright, but with [Laura Stevenson], I’m pulling back a bit. I’m super worried I’m gonna say something and not be able to take it back. Usually, I just talk and talk and talk until I’ve filled the space with idiocy. I really need to be careful now, which is a new thing for me.”

While crafting this pained collection of songs, glints of beauty did peek through the darkness. In the summer of 2019, immediately after playing the last show of a tour with Craig Finn to support The Big Freeze, Stevenson and Campbell learned that she was pregnant with their first child. By the time she was ready to record Laura Stevenson near the end of that year, she was five months pregnant. Pending motherhood allowed her to reflect on the anguish of the difficult preceding year with more perspective, and even some hard-earned peace of mind. She describes the record as a purge and a prayer—at once a primal scream and a meditation on the tranquility that followed. “I was looking at the events retrospectively, through this new lens, having this person inside me that I need to protect,” she says. “So there’s this crazy anger, but a serene and protective vibe.”

The best example of the album’s duality comes immediately, on opener “State,” the heaviest and most biting track not just on the record, but in Stevenson’s entire catalog. “I had a lot, a lot, a lot of anger, and I didn’t know what to do with it, and it scared me,” she says of the song. There is rage and catharsis behind the clobbering drums and her atypically heavy guitar pounding. But, through her gritted teeth, there is also clarity as the song fades into a calmer place in which she checks her temper, humming, “I’m in a state again, but I stay polite, I stay polite.”

Shortly after finishing the recording sessions for the album, Stevenson made her NPR Tiny Desk debut, accompanied by a three-piece string section. “When I said ‘yes’ to doing this Tiny Desk, I wasn’t pregnant yet, and now…” she said between songs, shifting her guitar to the side to show off her protruding baby bump, “with the passage of time, I’m six months pregnant today.”

The following month, she was mixing Laura Stevenson with producer John Agnello in Marlboro, New York, a town that holds personal significance because, she says excitedly, “Snooki is from there!” There was a moment during the session that stood out to Stevenson as peculiar. “One of the interns at the studio was reading the newspaper, and he said, ‘Oh, wow, there’s something going on in China,’ and he started telling us all about this virus,” she recalls. “Then, in February, at my baby shower, my sister was like, ‘You’ve got to buy all the food you need, get all the water you need. You’re not gonna see your friends for a really long time. This is serious.’ At first, I was kind of like, ‘OK, suuure,’ but then I started buying beans and rice, just in case. And then… shit hit the fan right before I gave birth.”

By the time Stevenson went into labor, in the third week of March, the world was only a few days into its battle with its crippling new nemesis, COVID-19. Worldwide cases had just surpassed 300,000 and were climbing fast. Even the hospital in which she gave birth was ill-prepared to handle the spread. “There was only one person wearing a mask in the hospital, the midwife that was supposed to deliver my baby,” Stevenson says. “But then she ended up leaving that night because she wasn’t feeling well, so we were so freaked out. We showed up with Lysol wipes and hand sanitizer and wiped everything down. We weren’t allowed to leave our hospital room.”

Stevenson gave birth to a girl and, needless to say, raising a newborn during the early stages of an international public health crisis was not easy. “Luckily, we had a few friends who lived alone and we had them go out and buy us two months’ worth of groceries,” says Campbell. “We had an auxiliary freezer delivered to us and filled it with $800 worth of food. We didn’t go anywhere for like five months.”

“Plus, I was having trouble breastfeeding and there was a formula shortage because of the pandemic,” says Stevenson. The couple eventually hired a lactation consultant who had to change clothes in their driveway before entering their home as a safety precaution. “For the first three months, babies don’t have an immune system. And right before she was born, a seven-week-old baby in Connecticut died of COVID. So I was trying to get her to seven weeks, and then to three months, all these little milestones.”

Stevenson’s daughter recently turned one, happy and healthy. She’s started saying a few words, too. “Purple” and “bubble” are her favorites. Even casual fans of Stevenson’s music are well aware of the dysfunctional family dynamics she grew up around as a child, as they’ve become themes that have run through many of her albums. But it’s a cycle she’s determined to break now that she has a daughter of her own. “There was a lot of fucked up shit that happened in my house when I was a little kid that definitely messed me up,” she says. “You become the parent you wish you had. I just want to give her the best life possible. I want to do everything right. I’m not gonna do everything right, but I’m really gonna try. I want to get her to Mars.”

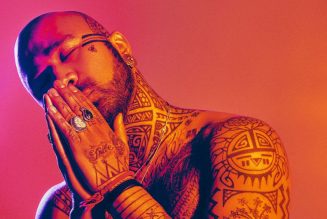

When trying to find an image that would suit Laura Stevenson, a record about surviving pain and trauma, Stevenson took a positive approach. She had a painting commissioned of her favorite photo of herself, which Campbell took in their living room. “The first time I’d ever had a photo of me on a record cover, it was The Big Freeze. I was wearing a hat and trying to look all glammed up. I didn’t look like myself,” she says. “But this one is the most me I’ve ever felt in a photograph. I was in my house, I was happy, I was nursing our child, my dog was at my feet. I was wearing a robe, and Harry Nilsson is wearing a robe on his record cover hanging above me. It was perfect.”

The homebody upstate mother on the cover might be a different Laura Stevenson than longtime fans remember from the Brooklynite troubador on her debut, A Record, and a far cry from the bombastic keyboard-smasher she was in the Jeff Rosenstock-led Long Island punk rock collective Bomb the Music Industry! But this is who Laura Stevenson is now. Settled, resolute, content.

“I feel like, back then, I was not as sure of myself as I am now,” she says. “I was more self-conscious, wanting to be accepted by people. I was always writing for myself, but I think I was holding back. I didn’t want to show people who I was or be vulnerable. I don’t know if it’s age or where I’m at in my life, but I do not give a fuck anymore, which is really…” She looks around the room once more, scanning the reminders of her daughter scattered about as she again searches her tired brain for the right word. Then, it strikes her. “…Nice.”