Advances in AI and satellite imagery allowed researchers to create the clearest picture yet of human activity at sea, revealing clandestine fishing activity and a boom in offshore energy development.

Share this story

Using satellite imagery and AI, researchers have mapped human activity at sea with more precision than ever before. The effort exposed a huge amount of industrial activity that previously flew under the radar, from suspicious fishing operations to an explosion of offshore energy development.

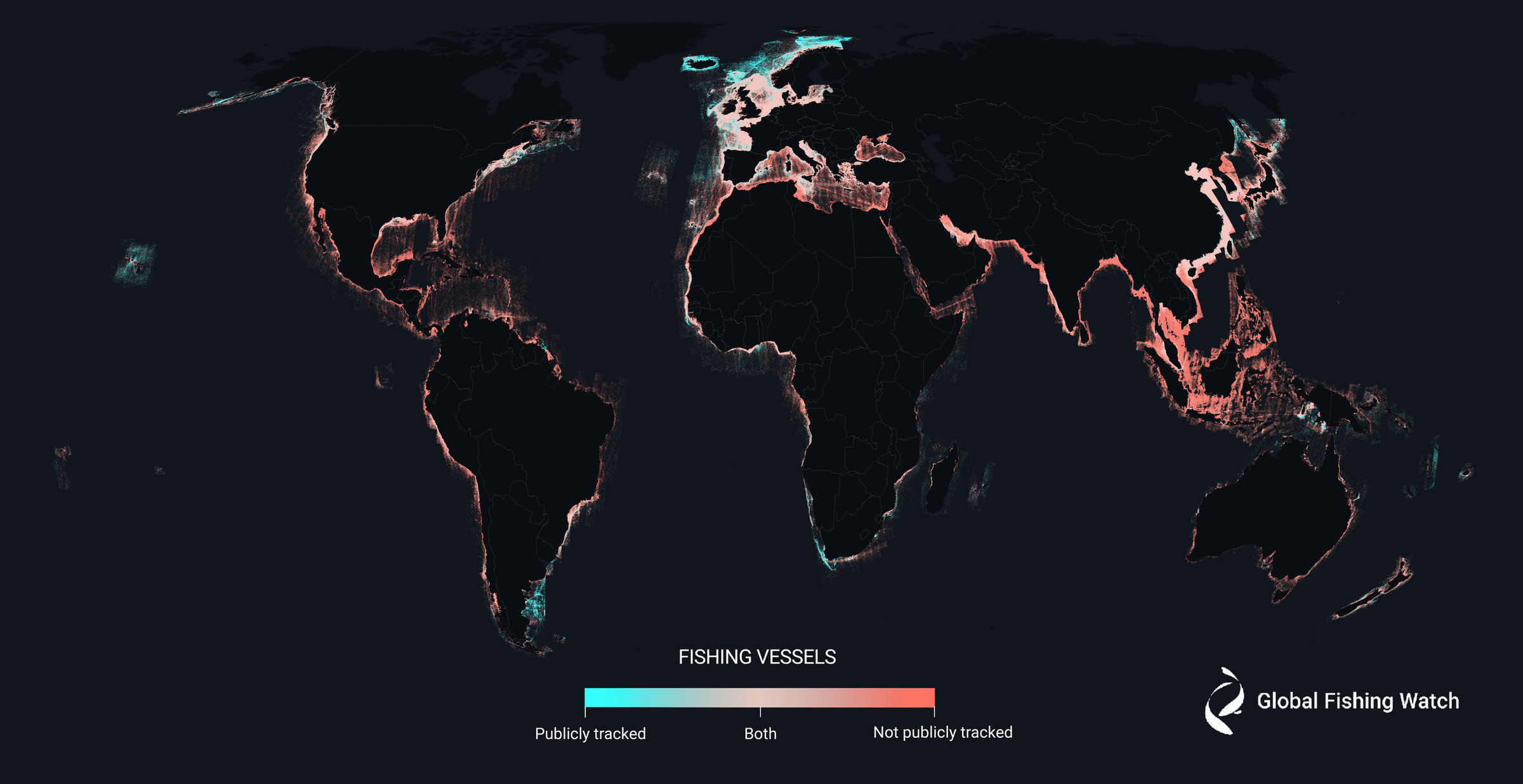

The maps were published today in the journal Nature. The research led by Google-backed nonprofit Global Fishing Watch revealed that a whopping three-quarters of the world’s industrial fishing vessels are not publicly tracked. Up to 30 percent of transport and energy vessels also escape public tracking.

Those blind spots could hamper global conservation efforts, the researchers say. To better protect the world’s oceans and fisheries, policymakers need a more accurate picture of where people are exploiting resources at sea.

Nearly every nation on Earth has agreed to a joint goal of protecting 30 percent of Earth’s land and waters by 2030 under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework adopted last year. “The question is which 30 percent should we protect? And you can’t have discussions about where the fishing activity, where the oil platforms are unless you have this map,” says David Kroodsma, one of the authors of the Nature paper and director of research and innovation at Global Fishing Watch.

Until now, Global Fishing Watch and other organizations relied primarily on the maritime Automatic Identification System (AIS) to see what was happening at sea. The system tracks vessels that carry a box that sends out radio signals, and the data has been used in the past to document overfishing and forced labor on vessels. Even so, there are major limitations with the system. Requirements to carry AIS vary by country and vessel type. And it’s pretty easy for someone to turn the box off when they want to avoid detection, or cruise through locations where signal strength is spotty.

To fill in the blanks, Kroodsma and his colleagues analyzed 2,000 terabytes of imagery from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 satellite constellation. Instead of taking traditional optical imagery, which is like snapping photos with a camera, Sentinel-1 uses advanced radar instruments to observe the surface of the Earth. Radar can penetrate clouds and “see” in the dark — and it was able to spot offshore activity that AIS missed.

Since 2,000 terabytes is an enormous amount of data to crunch, the researchers developed three deep-learning models to classify each detected vessels, estimate their size, and sort out different kinds of offshore infrastructure. They monitored some 15 percent of the world’s oceans where 75 percent of industrial activity takes place, paying attention to both vessel movements and the development of stationary offshore structures like oil rigs and wind turbines between 2017 and 2021.

While fishing activity dipped at the onset of the covid-19 pandemic in 2020, they found dense vessel traffic in areas that “previously showed little to no vessel activity” in public tracking systems — particularly around South and Southeast Asia, and the northern and western coasts of Africa.

A boom in offshore energy development was also visible in the data. Wind turbines outnumbered oil structures by the end of 2020. Turbines made up 48 percent of all ocean infrastructure by the following year, while oil structures accounted for 38 percent.

Nearly all of the offshore wind development took place off the coasts of northern Europe and China. In the Northeast US, clean energy opponents have tried to falsely link whale deaths to upcoming offshore wind development even though evidence points to vessel strikes being the problem.

Oil structures have a lot more vessels swarming around them than wind turbines. Tank vessels are used at times to transport oil to shore as an alternative to pipelines. The number of oil structures grew 16 percent over the five years studied. And offshore oil development was linked to five times as much vessel traffic globally as wind turbines in 2021. “The actual amount of vessel traffic globally from wind turbines is tiny, compared to the rest of traffic,” Kroodsma says.

When asked whether this type of study would have been possible without artificial intelligence, “The short answer is no, I don’t think so,” says Fernando Paolo, lead author of the study and machine learning engineer at Global Fishing Watch.“Deep learning excels at finding patterns in large amounts of data.”

New machine learning tools being developed as open-source software to process global satellite imagery “democratize access to data and tools and allow researchers, analysts and policymakers in low-income countries to leverage tracking technologies at low cost,” says another article published in Nature today that comments on Paolo and Kroodsma’s research. “Until now, no comprehensive, global map of these different types of maritime infrastructure had been available,” says the article written by Microsoft postdoctoral researcher Konstantin Klemmer and University of Colorado Boulder assistant professor Esther Rolf.

The technological advances come at a crucial time for documenting fast-moving changes in maritime activity, while nations try to stop climate change and protect biodiversity before its too late. “The reason this matters is because it’s getting more crowded [at sea] and it’s getting more used and suddenly you have to decide how we’re going to manage this giant global commons,” Kroodsma tells The Verge. “It can’t be the Wild West. And that’s the way it’s been historically.”