This piece was created in partnership with Afro Nation. Billboard and Afro Nation recently launched the first-ever official Billboard Afrobeats U.S. Songs Chart, tracking the most popular rising new music in the rapidly growing genre. The 50-position Billboard U.S. Afrobeats Songs chart, which went live last month on Billboard.com, ranks the most popular Afrobeat songs in the country based on a weighted formula incorporating official-only streams on both subscription and ad-supported tiers of leading audio and video music services, plus download sales from top music retailers.

When alté music, a genre defined by its inability to be conclusively defined as it moves through different genres and maintains a highly experimental form, began to enter mainstream Afrobeats music in the late 2010s, the fashion side of that genre, known as the alté subculture, also thrived. That subculture is less of a set of dressing styles and more of an ideology that encourages young Nigerians to tap into honest self-expression — essentially dressing how they would personally like to, and not in the ways that conform to the socio-cultural dictates of the country.

It is that same ideology that is defining the role of fashion in Afrobeats music today, particularly for artists like Rema, CKay, Cruel Santino, Wizkid, Burna Boy, Amaarae, Tems and Adekunle Gold. With the genre gradually staking a claim on the global music scene, Afrobeats artists are learning to define their sense of fashion more by personal sensibilities and less by popular trends.

Fashion has always played a vital role in how Afrobeats artists express their artistry. In the late 1960s, when Fela Anukulapo Kuti returned to Nigeria from studying at the London School of Music in England, he returned as a different artist. While away, Fela had become heavily influenced by American jazz, which he would go on to combine with didactic cultural Yoruba music, upbeat West African highlife and funk to create what we now know as Afrobeats music.

But it wasn’t just Fela’s music that found redefinition over time: his politics – which focused on mental slavery, corruption, economic disparity, and the many ways in which Black leaders in Black nations mistreat their people while championing white supremacy — also took a pivotal turn. And a part of Fela’s artistry that ties this all together, however, was the way in which his physical appearance — through his intentionally pan-African and anti-colonial fashion choices — complemented his music.

Fela’s fashion is often the next thing, after his music, that people mention when they talk about him. “[Fela’s] style of sequined/Ankara tight pants with tight shirts was a statement,” Ayomide Tayo, a senior entertainment editor at Opera News, explains. “The Afrobeat creator was highly pan-African, and his dressing doubled down on his belief that African culture is supreme. It also separated him from other artists in the Nigerian music scene. He loved being a rebel.”

Tayo also argues that, aside from simply grounding himself in his roots, Fela was also particular about breaking the rules around fashion and setting future-facing trends. “For someone whose music was highly African, It would have made more sense if he dressed in traditional attires like King Sunny Ade or Chief Ebenezer Obey,” says Tayo. “Fela instead decided to dress in an Afro-futuristic way to let people know he was a trendsetter who wanted to take Africa forward.”

But Fela wasn’t the only one who tapped into fashion to complement his sound. Many Afrobeat artists in his time — and in fact, several other Nigerian artists who dabbled in genres like reggae or rock — often embodied the fashion senses typically associated with the genres they were working in.

Billboard Teams Up With Afro Nation to Launch New U.S. Afrobeats Songs Chart

In the ‘80s, for instance, Majek Fashek often donned typical Rastafarian outfits, complete with long dreadlocks when performing his reggae-inspired tracks. At the time, Tayo explains, “Reggae was used to speak about the hardship in the country, so the style of dressing suited the theme.”

As time went on, between the late ‘90s to the early 2000s, the themes and preoccupations of Afrobeats began to take on a lighter, more luxurious tone. While songs sometimes touched on socio-cultural concerns, much of the music coming out at that time also touched on love, success, friendship and community.

There was an uptick in Afrobeats artists of that time wearing designers and brand names, with much of their sound also heavily influenced by hip-hop culture. At the time, “American urban fashion was trendy,” Tayo says. “Teenagers and young adults wore shirts and jeans from designers like Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger, Polo by Ralph Lauren and others. Hip-hop culture was in full swing in Nigeria at this time. Radio stations played the latest songs from Puff Daddy, Jay-Z, 2Pac and others. TV stations showed rap and R&B videos. American hip-hop stars were idols, and everyone wanted to dress like them, including the foundational Afrobeats acts.”

Tayo cites Afrobeats legends such as 2face Idbia, Tony Tetuila and Eedris Abdulkareem as some of the artists for whom appearing in these types of clothing was a strategy to make them appear on par with beloved American stars. And for that time, their strategy worked.

In no time, however, fashion in Afrobeats began to take a more self-defined turn, with artists returning to the core of expressing the specificity of their music — not necessarily the genre they worked in — through their clothing. Whether it be in Afropop, Afrorock or contemporary highlife, artists prioritized what they liked over what was immediately fashionable.

There was D’banj, who would go shirtless in most of his shows as a reinforcement of his sex-symbol image, and P-Square, taking inspiration from Michael Jackson’s form-fitting, militant clothing. These styles often matched their highly danceable tunes, but were reinterpreted in a very Nigerian — and refreshingly personal — way.

Meanwhile, female Afrobeats artists like Tiwa Savage, Yemi Alade, Goldie Harvey and Seyi Shay have all used fashion as a direct tool to dismantle conservative ideas of womanhood in the country. By opting for clothes that presented them as women assured in their sexuality and desires, these artists often stirred controversies but significantly paved the way for the full and unbridled expression that emerging female acts now possess.

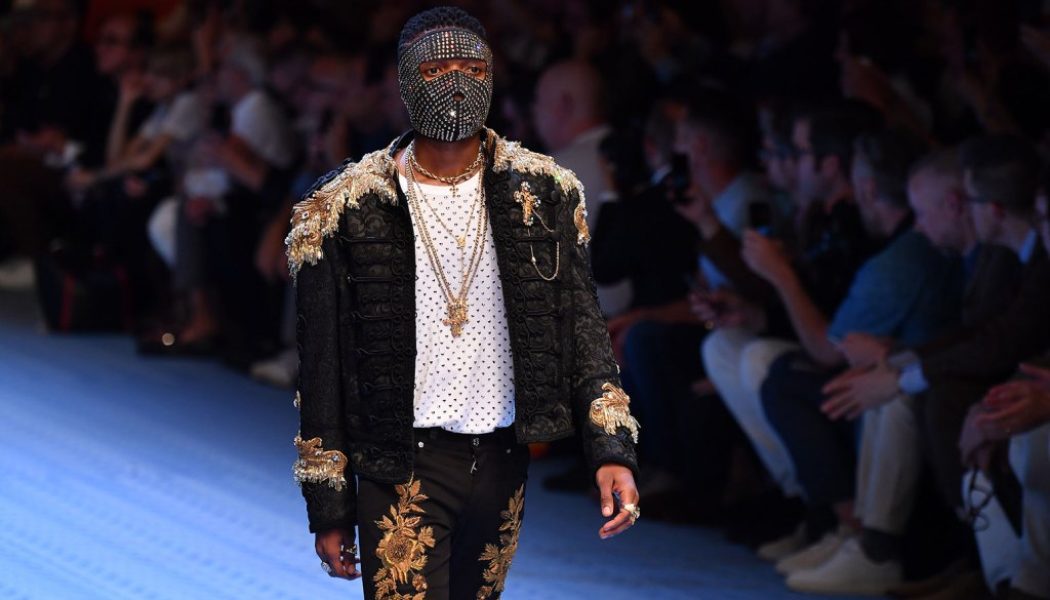

That individualistic approach has trickled over into the way the new generation of Afrobeats stars aligns their fashion sensibilities to their artistry. Now more than ever, many are leaning towards high fashion, favoring both loud and understated looks from prestigious brands. Think Wizkid on the Dolce & Gabbana runway, or Burna Boy hanging out with the late fashion icon Virgil Abloh. Brands such as Gucci, Fendi, and Bottega Veneta are name-checked on many records. And on an artistry level, “it has influenced them to create lush and sultry records to match their image,” Tayo adds.

Twenty-two-year-old stylist Benson Ado is one of the rising talents crafting the sartorial image of Afrobeats artists, one outfit at a time. Having worked with some of the major stars in the genre — Davido, Ckay, Badboytimz and Bella Shmurda are among his clients — Ado has grown to understand the different ways in which the music these artists create directly influences what they choose to wear.

“If you’re making more emotional music,” Ado says, “You will go for more colors and softer silhouettes.” With CKay, for instance, Ado’s approach to styling has been to explore colors that complement the love-tinged elements of his songs, while for artists like Davido, Ado would typically go for pieces that accentuate his personal style, while remaining comfortable and still in touch with luxury products.

Dunsin Wright, who styles some of the continent’s established female stars including Tems, is also taking note of the self-defined, honest approach most Afrobeats artists are attempting – opting to stay true to their identities, rather than join the flock.

“Tems’ aesthetic can be described as pretty casual, classic but always chic. She leans towards darker, muted tones generally,” Wright explains. “She loves layering and balance, so like an oversized jacket with a crop or sheer top underneath, or a cute co-ord. We have been experimenting a lot more lately with different styles and silhouettes, her style is constantly evolving, which for me reflects the dynamism in her music.”

However, stylists like Efe Asagba — who has also worked with Davido, Rema, CKay and others — believes that complete individualism is still lacking for some Afrobeats artists, and more needs to be done for Afrobeats to create personalized styles. “Honestly, I’ll say only a few artists have really personalized their style,” Asagba says. “For example, when I think of a Wizkid outfit, I think of breathable pieces, button-ups, slip-on and string of monochromatic Issey Miyake fits he wore throughout his U.S. tour.”

The rise of Afrobeat artists paying attention to their fashion choices also comes at a time when the African fashion industry, from Nigeria to Ghana, is seeing a positive explosion on the globe. This makes it easier for Afrobeats stars to align with established African designers while also staying grounded in their artistry.

“I just think in general the progression of fashion in Nigeria will cut across industries,” says Dunsin, about what this represents for the future of the industry. “The rise in social awareness, as it always has, will continue to influence the value that people place on freedom in style and expression, and so we’ll see bolder, more experimental choices. We’re beginning to shop more with so many talented emerging designers across West Africa. I believe we’ll see a lot more intention across the board, from social media to music videos. Style is acknowledged more now as an integral role to the story or theme an artist is communicating at any given point.”

Nelson C.J is a Nigerian culture journalist published in The New York Times, TIME Magazine. Rollingstone, Eater, BuzzFeed, Architectural Digest, Teen Vogue, I-D, Dazed, Vice, and other places. You can find him on Twitter.

[flexi-common-toolbar] [flexi-form class=”flexi_form_style” title=”Submit to Flexi” name=”my_form” ajax=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”post_title” class=”fl-input” title=”Title” value=”” required=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”category” title=”Select category”][flexi-form-tag type=”tag” title=”Insert tag”][flexi-form-tag type=”article” class=”fl-textarea” title=”Description” ][flexi-form-tag type=”file” title=”Select file” required=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”submit” name=”submit” value=”Submit Now”] [/flexi-form]

Tagged: afro nation, Afrobeats, entertainment blog, FEATURES, music, music blog