A famous maxim from the Talmud reads “whosoever saves a life, it is as though he had saved the entire world.” For world leaders gathered at Cop28, the task of saving the entire world from climate change’s worst impacts must include policies that lead individuals to a longer, happier life, experts say.

“I would go as far as to say that there’s probably an inverse relationship between your carbon footprint and how long you’re going to live. In other words, the smaller the carbon footprint, the longer you’re going to live. It’s a correlation,” says Dan Buettner, chief executive of Blue Zones LLC, who has led research to identify the world’s longevity hotspots with National Geographic.

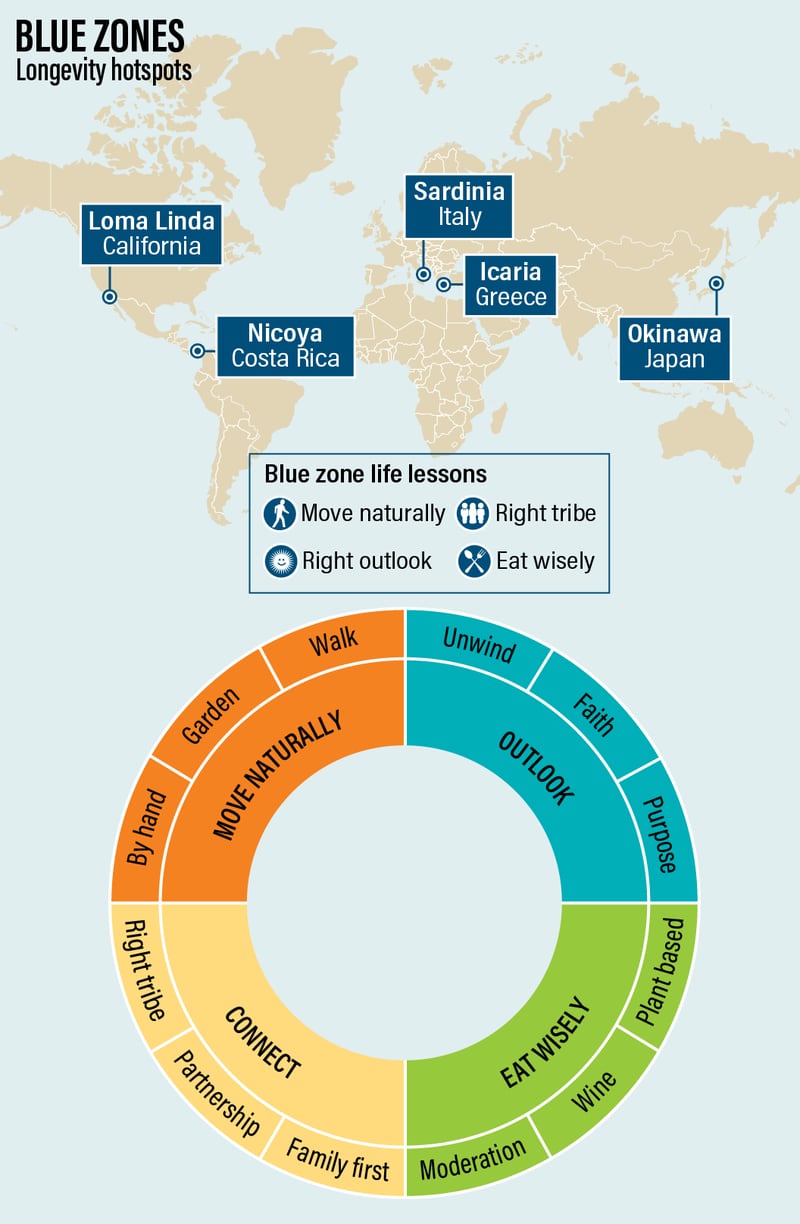

These five distinct areas, where people reach the age of 100 at 10 times greater rates than in the United States, were dubbed “Blue Zones”, and they offer lessons in building climate solutions.

Across an array of geographic locations and cultures, from Okinawa, Japan, to Icaria, Greece, research found about nine common denominators between these five clusters of longevity.

Natural, daily movement, a plant and grain-heavy diet, a strong sense of purpose and community are among the driving factors that research has found to produce longer, healthier and happier lifespans.

Mr Buettner has taken these principles across the United States, working with policymakers, businesses, schools and individuals to shape the environments of the Blue Zones Project Communities.

The US National Institute of Health in 2016 published a study on the project’s work, where it found “the Blue Zones Project Communities have been able to increase life expectancy, reduce obesity and make the healthy choice the easy choice for millions of Americans”.

“Putting the responsibility of curating a healthy environment on an individual does not work,” the NIH report stated.

The takeaway is clear: especially in the US and other industrialised societies, longevity requires policy. And many longevity-producing policies lend themselves to lower carbon emissions and more resilience to the consequences of climate change.

Transport

Transport policy is “the very first thing that every leader should be looking at” to improve their constituents’ longevity, Mr Buettner told The National.

“If you’re a true leader, your job is to produce the highest level of happiness and health among your people … and one of the easiest ways to do that is become walkable and bikeable,” he added.

Mr Buettner highlighted Singapore, though not an official “Blue Zone”, as a key example of where a less car-dependent system has generated life-preserving results.

“Only 11 per cent of people have a car, the other 89 per cent of people walk or take public transportation, or bike. And not coincidentally, they all get 8,000 to 10,000 steps a day. And they have the highest disease-free life expectancy in the world.”

Based on 2018 International Energy Agency (IEA) data, Singapore ranks 126th of 142 countries in terms of CO2 emissions per dollar of GDP, though its oil storage and refining facilities sector still struggles with high emissions.

Other examples of cities that addressed traffic and walkability issues with “smart policy” include Copenhagen and Amsterdam.

“Their cities were choked with traffic in the mid 1970s,” he said, but they have created “walkable places, where people not only have some of the lowest rates of obesity and chronic diseases in Europe”.

Importantly, Mr Buettner says, “they’re also the happiest.”

That shift has assisted the cities in their own emissions reduction goals, too.

Copenhagen, for example, is among the cities who have committed to be carbon neutral by 2025. And though it has a long way to go to achieve that goal within the next two years, according to Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance, the city has reduced its emissions by about 42 per cent since 2005.

Food

Climate change impacts a major factor for Blue Zones: how and what we eat.

Blue Zones, though scattered across the world with different topographies and cuisines, have diets which all have lower carbon footprints.

“So instead of eating beef, and which takes 11 pounds of grain to make one pound of beef – and there’s methane and there’s the run-off, [Blue Zones] are eating mostly beans and grains and things that grow in their gardens,” said Mr Buettner.

Laurie Beyranevand is the director of the Centre for Agricultural and Food Systems (CAFS) at the Vermont Law and Graduate School.

Partnering with a team at Harvard University, CAFS has developed a Blueprint for a National Food Strategy, which models a more comprehensive and streamlined approach to US food policy.

Ms Beyranevand says climate-friendly food systems mean “countries need to individually start to think about how to be more self-sufficient and more food sovereign,” and to start “shortening the food supply chain”.

“Like on imports, not being dependent on them so much, and instead having them as a back filler,” she told The National.

“If we did that I do think that you would start to see more emphasis on growing fruits and vegetables and things that we should be consuming more regularly,” she added.

Ms Beyranevand said “the Blue Zones are incredible examples” of a healthy food model, and she believes broadening the zones could expand climate resiliency, too.

“It would be great to see those Blue Zones expand into Blue Regions where there was a broader geographic focus. And then they might be less susceptible to climate impacts and have more resilience.”

Lessons for Mena

But the American diet is expanding globally. “It’s the American food culture that’s killing [people]. As soon as the standard American diet arrives, your obesity rates and diabetes rates and heart disease rates skyrocket, and their life expectancy numbers plummet,” said Mr Buettner.

That has had a particular impact on Gulf countries in the Middle East.

“They’ve been too fast to adopt a western diet. And they’re horribly unhealthy,” added Mr Buettner.

“The Middle East can learn a lot from those [Blue] zones, quite honestly,” he added.

In the GCC region, the incidence rate of obesity is estimated to be up to 40 per cent, according to research published by the Saudi Medical Journal and the US National Institute of Health.

The prevalence of excessive weight and obesity in Gulf countries “increased from 4.3 per cent in 1980 to 34.9 per cent in 2009,” the research found.

But that rapid transition, Mr Buettner says, means there is an opportunity for Gulf countries to change course.

“If you go back three generations, the diet is not so bad … I think it has enormous potential.”

“Grandparents alive today lived in an environment or way of life that could very well reverse that whole disease paradigm.

“This type of Blue Zone set of practices unique to the Middle East – that we should be paying attention to,” he told The National.

Updated: December 11, 2023, 8:00 AM