I N THE EARLY DAYS of house music, nobody hustled harder than Vince Lawrence.

Vince grew up on the South Side of Chicago. As a teenager in the late 1970s and early 1980s, he was urbane and in the know: He liked Izod shirts, white K-Swiss sneakers, and straight-leg jeans; he ran hip parties, loved import records from Europe, and aspired to make music of his own. A lot of what he and his friends were into, he remembers, “came from us reading GQ and wishing we were rich.”

Around then, there was a specific vibe at Chicago’s high school parties, downtown gay clubs, and on local radio — underground but not exclusive, sophisticated but not so preening that nobody wanted to dance. It was “house” culture, named after a club called the Warehouse. At first, “house music” meant anything that the club’s DJ, Frankie Knuckles, played — disco, Italo disco, Philly soul, New Wave, even punk. Amid that swirl, perfectly on-beat digital rhythms meant DJs could experiment with seamless mixing, and synthesizers were becoming affordable enough to be available outside of studios. The result was a new sound — heavy, stripped-down, synthetic but groove-rich — made by Vince, his friend Jesse Saunders, and other, mostly Black, kids. It was what the world came to know as house music, and for all of its epochal innovation, Vince says it had a simple appeal: “It was the best we could do, and we knew it worked at the parties.”

Vince and Jesse couldn’t wait to get the new sound onto vinyl, and brought it to Larry Sherman, a thirtysomething son of Chicago who owned a record-pressing plant on the South Side. Soon, Trax Records was born. In the label’s early days, Vince was busy beyond just making his own music. In the daytime, he and a small staff ran the presses and put records in sleeves and jackets, and Vince made sales calls and negotiated with distributors, among other things. At night, he went to the club to hand out promo pressings to DJs and see how the dance floor responded to new tracks. Vince says he designed the Trax logo, inspired by the stark, highly legible block-capital typefaces associated with the industrial-music scene. (He also figured that a stark, white-on-black logo would catch the eye of a DJ in a dark club rummaging through vinyl for their next jam.)

Trax captured the Big Bang of a youth movement: It was the first label, in January 1984, to release house and, in the space of two years, put out both the genre-defining “Move Your Body (The House Music Anthem),” by Marshall Jefferson, and the genre redefining “Acid Trax,” by Phuture. The latter song gave the world the first real taste of acid house, the subgenre that later crossed the Atlantic and took over youth culture in the U.K. in a loud, shrill, gorgeous, hormonally haywire kind of way. What Trax helped start has since synthesized into the $7-billion-a-year EDM business, and Chicago house has recently been growling through the mainstream in major ways: Beyoncé’s Renaissance and Drake’s Honestly, Nevermind, both from last year, were homages, with house grooves coursing through their tracks.

But today, the house of Trax is in disarray. Vince and 22 original Trax artists are locked in a legal battle over the rights to their classic music with the current co-owner of the company, Rachael Cain, Vince’s onetime friend and Larry’s ex-wife. It amounts to a civil war over the catalog of arguably the most important label in the history of house music.

Vince recently turned 59. A few years ago, his wife, Tara, asked him to start getting his affairs together; life insurance, that kind of thing. They have a nine-year-old son, London, to think about. Vince, who left Trax in 1986, started to pull documentation of his music from a long and varied musical career, to get it all in one place for his family, just in case. But when he began to look at statements that laid out who owned the publishing for songs he had written, he says he was baffled. He found some 30 songs, he says, that had nothing to do with Trax — that, he claims, he recorded for other labels or for himself — had been registered to the label, meaning Trax, in effect, owned the songs and was therefore getting checks that, Vince says, he should have been getting.

Once he grasped the scope of the irregularities, Vince called Rachael, who has owned 50 percent of Trax since 2006, as a result of her divorce from Larry. (Larry died in 2020; his widow, Sandyee Sherman, owns the other half.) “Rachael,” Vince remembers telling her, “Give [the songs] back. You’re making a mistake.” Rachael, he says, refused, and Vince says he got a message from Trax saying something to the effect of “We don’t have a contract [proving we own the songs], but we’re going to assert a claim anyway, until a court says otherwise.”

“‘What you’re telling me is you know you have no deal, you know that it’s mine, and you’re not giving it to me unless I sue you?’” Vince recalls saying. “So I said, ‘My son is going to have my [songs], and I don’t give a fuck anymore.’” (Rachael denies the exchange happened; “Vince fabricated that scenario,” she says.)

Vince says he told Rachael’s lawyer, “You’re going to remember the day when all I was asking for was these 30 songs.”

Almost since the earliest days of the label, Vince says, there has been an ever-growing resentment among classic Trax artists. They say they have been deprived of what’s rightfully theirs by Larry, by Rachael, or by both. And all it took was a little encouragement to bring them into battle.

In October, Vince and his lawyer, Sean Mulroney, filed a suit against Rachael, Trax, Sandyee Sherman, and the Sherman estate on behalf of the plaintiffs, 22 men and one woman, mostly Black, all of them first-wave Chicago house musicians. The plaintiffs claim they never signed contracts selling all the rights to their work to Larry, but that he — and later Rachael — simply registered the copyright to their work to Trax anyway. They believe Trax either sold copies of that music or licensed it for movies, video games, etc., and pocketed the money. (Rachael denies that, claiming Trax has had valid contracts for every piece of music it controls, though she admits that some of the physical contracts have been lost along the label’s tumultuous and winding path.)

Some of the plaintiffs are the superstars of Trax, like Jefferson, but they also include musicians who doubled as workers in the Trax warehouse back in the day, as well as Maurice Joshua, who launched a career with Trax and went on to win a Grammy for his remix of Beyoncé’s “Crazy in Love.” Several are people Rachael, who’s been involved with house music from the beginning, once considered to be close friends.

It turns out that Rachael has her own story to tell, about why she has clung to Trax through ordeal after ordeal, in the face of increasingly bitter opposition. She’ll tell you that she’s risked everything in order to fend off bigger businesses bent on taking the catalog, and that all she gets in return is anger and recrimination.

THE COPS SAID IT WAS ARSON — that Larry Sherman and his pal Richard Randazzo set fire to an old tavern, Smugglers, just off Chicago’s Magnificent Mile. Larry, according to Rachael, would claim he was called to a meeting, and the door to Smugglers was booby-trapped, that he tripped something when he opened it.

Either way, on Sunday, Aug. 31, 1980, there was an explosion that set Smugglers ablaze. A man later identified as Randazzo was seen running from Smugglers. Larry ran away too, bleeding from the head. They both jumped in a car and sped away. Larry got third-degree burns and ended up in the hospital, according to Rachael.

Randazzo was acquitted of arson; Larry was never charged. Larry’s brother, Curt — and Larry himself, according to Rachael — believed the explosion was meant to kill Larry. The Mob, probably — some kind of gangsters, anyway. (Vince lived with Larry for a while, and says Larry sometimes talked about being involved with organized crime. “You know how they say ‘Fell off a truck’?” asks Vince. “When they show up with the whole trailer, you think, ‘Maybe some of this is true.’”)

The point is, Larry was involved in the dark side of Chicago business for much of his life — and when he got into the music industry, it wasn’t exactly to become Clive Davis. He and Curt had grown up on Chicago’s South Side. Their dad died in 1955, when Larry was six. His mother had to take over the family business, a machine shop that made gears. “She lost that,” Curt says, “and after that it was just kind of a struggle to survive.… We hustled from the beginning.” Curt says Larry got into stealing cars, then robbing rail freight. Curt knew this, not least because he and his brother got into the trucking business together, and Larry used their docks to move the stuff.

When Larry started in the record business in the early 1980s, it was a neat little polka hustle. Chicago has one of the world’s largest Polish populations outside of Poland, and back then Bel-Aire Records —owned by Eddie Blazonczyk of Eddie Blazonczyk and the Versatones, the man behind “Polish and Proud of It” and “Everybody Polka,” among others — was, according to Vince, the largest polka label in America. As Vince remembers it, Larry bought the only two vinyl presses in Chicago from a guy whose company had been manufacturing the Bel-Aire catalog. “So Larry was making these records for Eddie Blazonczyk,” Vince says. “Selling shit tons of polka records.”

He also bootlegged. Wurlitzer, as Vince remembers, had stopped producing the super-thick 78 rpm singles that fit its jukebox mechanism, so Larry was copying all kinds of music onto these chunky old 78s and selling them to enthusiasts. (Larry was eventually indicted on 51 counts of unlawful use of sound recording, though he pleaded guilty to only a single count. He was sentenced to community service and probation, and had his case disposed of.)

Meanwhile, Vince and Jesse Saunders started making tracks with a drum machine, and when one of their tunes, “On and On,” took off at an underage nightclub called the Playground, and other teen parties, Vince knew from his dad (who owned his own label) where to go to get it pressed up: at Larry Sherman’s plant. Once Jesse and Vince showed off their own record at the Playground, every DJ at the parties, clubs, and the house radio station seemed to show up at Larry’s warehouse with a tape to pitch.

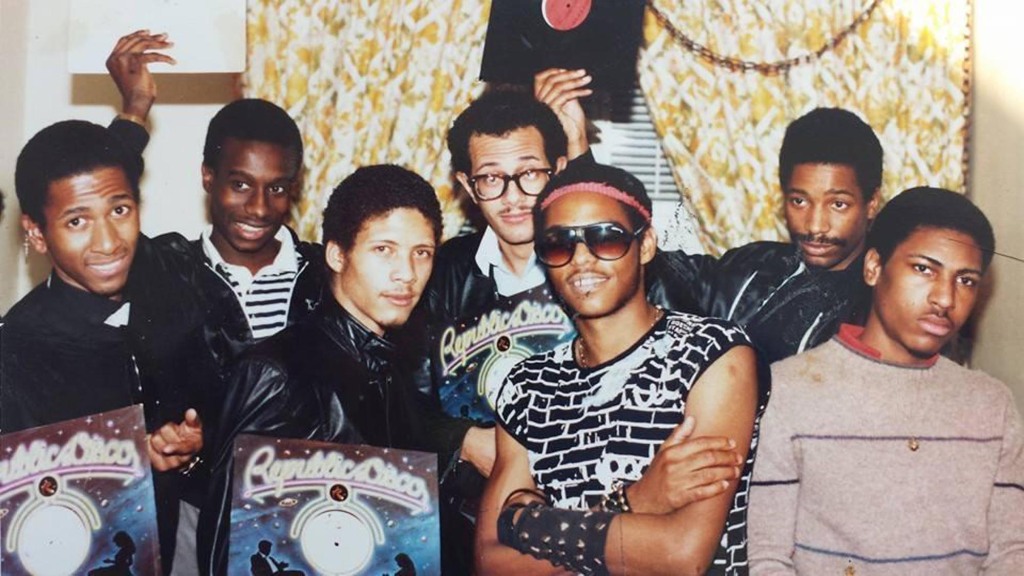

Vince (second from left) and Jesse Saunders (second from right) in 1984. Courtesy of Vince Lawrence

Largely by virtue of owning the warehouse and being a decade or so older than Vince and Jesse, Larry was by most accounts the de facto head of Trax. He liked to operate in cash; he prided himself on squeezing deals out of the young, unrepresented, mostly Black artists. Rachael says he kept a stack of crisp bills on his desk when he was negotiating — he’d tell an artist that they could have a wad of cash now, or they could take the contract away and have a lawyer read it — but the pile of cash might be gone when they came back. He quickly became notorious for failing to cough up the scant advances and royalties he did promise the acts. Vince says there was only a halfhearted attempt at a system for calculating or paying royalties. Mostly, he says, artists would get a somewhat arbitrary sum of money if Larry wanted to entice them to record more music.

Vince says he never signed any ownership paperwork for the label. He thinks the company was only incorporated when orders became big enough that Larry was reluctantly forced to start using checks.

In his memoir, The Diary of a DJ, Marshall Jefferson remembers a time when Larry for some reason stuck only Jefferson’s name on “Move Your Body (The House Music Anthem).” In fact, the record was made by Jefferson and three buddies: Curtis McClain, Rudy Forbes, and Tom Carr, who went down to Trax to confront Larry about it. Larry told them he’d paid Jefferson $150,000 for the record. (He hadn’t, Jefferson says.) Larry’s lie caused a whirl of mistrust and recriminations among the friends.

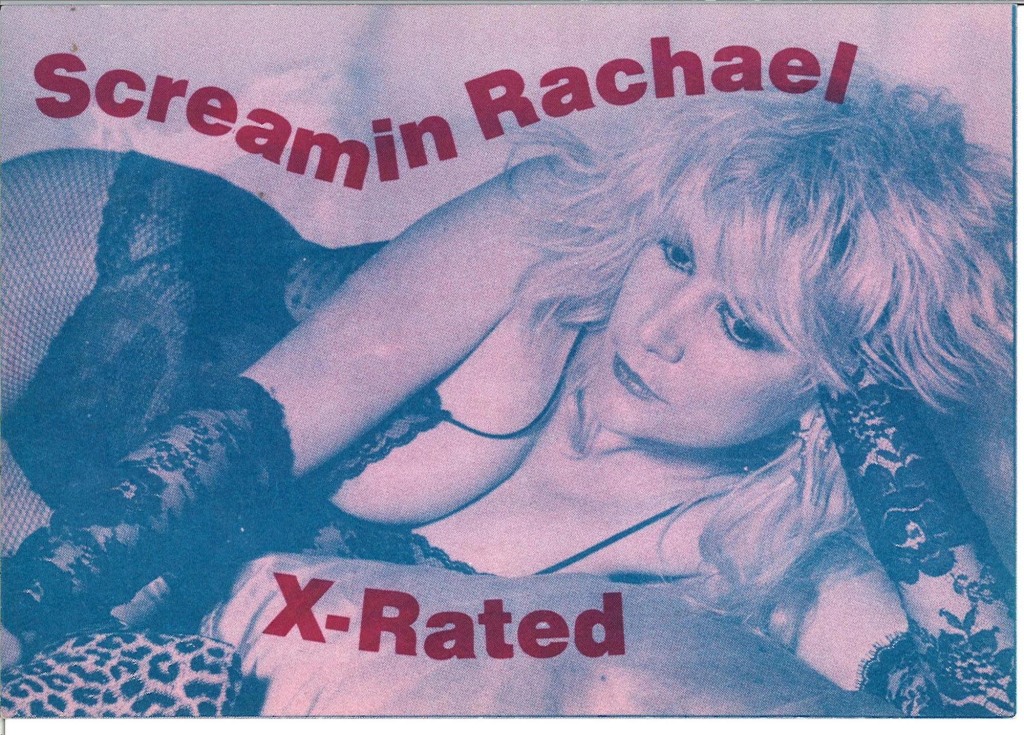

Meanwhile, in the mid-Eighties, Rachael was busy getting her own music career off the ground. She had grown up on Chicago’s North Side, enduring what she describes as a terribly lonely childhood. In 1984, under her stage name Screamin’ Rachael, she recorded an important track with Jesse and Vince, “Fantasy,” likely the first house track to feature a singer. Jesse called Rachael a “key ingredient” in the track and “a great rock vocalist” in his 2007 memoir, House Music: The Real Story.

The way Rachael remembers it, she met Vince and Jesse when they came to see her punk band, Screamin’ Rachael and Remote. That’s not how Vince remembers it. “I told my dad we needed to find a singer and we wanted somebody white, because there was a record called ‘Calling All Boys,’ by the Flirts,” he says. “We wanted somebody who sang like that. We saw pictures of Rachael in some punk band, and we were like, ‘Oooh, she’s good-looking. We can use that to sell records.’”

And after “Fantasy” came out, the way Rachael remembers it, they were a gang — Rachael, Vince, Jesse, and Jefferson. She says she and Vince used to take out Larry’s Corvette; she and Jefferson toured together, spent holidays together. As Jesse recalls in his memoir, Rachael gave him an added assist, persuading her pal, the late lawyer Jay B. Ross, to loan Jesse five grand to get Jesse’s label, Jes Say, off the ground. “Screaming Rachel … was once again an angel to me,” Jesse wrote. (Jesse, who is recovering from a stroke and answered questions for this story via email, appears to have changed his outlook since the book was published, now saying: “All she did was introduce me to Jay B. Ross, who proceeded to steal all my money.”)

Jesse, Rachael, and Vince all signed big record deals on the coasts in 1986 and left Trax behind. Vince and Jesse both went with Geffen, out of L.A.; Rachael signed with Arthur Baker’s Streetwise Records in New York, and did a deal with Warner Music Group’s German label, Teldec.

All three of them crashed. Rachael’s labelmates New Edition sued Streetwise out of existence, and Geffen just didn’t get Vince’s work, he says. Jesse formed Jesse’s Gang with Trax artist Duane Buford and singer Twala Jones, and got an album, Center of Attraction, onto shelves in 1987. But Geffen didn’t pick him up for another record.

Vince’s L.A. experience left him bitter, and soon he withdrew to Larry’s warehouse world. Vince started a new label, No L.A. Bull (pronounced “No Label”), in partnership with Larry, who fronted the vinyl and pressed the records. The profits usually came in the form of cash, which Vince and Larry simply split up on the spot. And just like the old days, Vince says, there wasn’t a contract between the two.

In 1989, Vince ended up making music for commercials. He was also making house remixes of pop tracks for about $20,000 each, doing a couple a month and making $300,000 or $400,000 a year between the two endeavors. After that, Vince put out records here and there on Trax or No L.A. Bull. Larry would give him $5,000 or he wouldn’t; with the commercials and remix income, it didn’t really matter. “So then I played with Larry for fun,” he says. “Not for my living.”

BY THE EARLY 1990s, Larry was living at an address that would one day house notable Chicagoans — perhaps the most notable living Chicagoans of all, in fact: the Obamas. The former polka-records guy had moved into 5046 South Greenwood Ave., the six-bedroom brick Georgian in semi-urban Kenwood that would become the Obamas’ place in Chicago during all eight of their years in the White House.

Around 1996, Rachael and Larry ran into each other on the beachfront promenade in Cannes, France. Larry was with the house superstar Joe Smooth, producer of the 1987 gospel-like house pillar “Promised Land”; all three were in Cannes for MIDEM, a music-industry conference. Larry saw Rachael from a cab and told her to get in.

Larry persuaded Rachael to come back to Chicago. Larry, she recalls, told her she needed a change, and he needed a star artist to record. Rachael said she’d come back, but only if he made her president of Trax — which he did, in lieu of a salary. (He also gave her a small stake in the company, and she also made cash, she says, by cutting international licensing deals for Trax-owned music.) Working for Trax was an exciting prospect. Rachael remembered the buzz around the factory, everyone pitching in with shrink-wrapping and boxing up records. And she’d learned a lot about the music business in New York, particularly working at Sugar Hill Records, the pioneering hip-hop label that had put out “Rapper’s Delight.”

Larry and Rachael started dating, and Larry moved her into what would one day be known as “the Obama house.” Rachael, it turns out, didn’t like being out there in Kenwood, so far from downtown, so they soon relocated to the chic address of Lake Point Tower, right on the shore of Lake Michigan.

But the giddy optimism of Rachael’s homecoming was soon replaced by something much darker. Not long after moving back to Chicago, she says, Larry hit her for the first time. It was over a vet’s bill. Boss, the Trax warehouse cat (so called because she liked to sit in Larry’s chair), needed $1,000 worth of care. They fought over it. “That was when he gave me my first black eye,” she says. On another occasion, Dec. 4, 1998, according to his arrest records, Larry “grabbed and jerked her left arm and slapped her” at Lake Point Tower. “[Cain] had to go to the hospital.”

Another time, Rachael says, Larry flew into a rage while spending the evening at a movie theater with Rachael and his daughter from his first marriage, Tessa. He got into his car and sped toward them, narrowly missing them. “Who knows what happened, but he got mad,” says Tessa. “Sometimes people just do stuff when they’re angry. Like slam on the gas and swerve the car.”

That night, Shar, Larry’s previous wife and Tessa’s mother, showed up and offered Rachael a place to stay. “[Tessa’s] mom came to kind of save us,” Rachael says. “And I still went away with Larry. I went to stay with Larry instead of going with them, which I probably should have.”

The couple married in 1999. It was a difficult relationship to understand, Rachael admits — even, at times, for her. “There were a lot of horrible things about Larry,” says Rachael. “But at the beginning, it wasn’t horrible like that. He was like a big kid in many ways, at least at first, before he lost his mind totally. He was a big Disney fanatic. He loved Beauty and the Beast, going to Disney [parks].”

On March 5, 2003, Rachael swore in a petition for an order of protection from Larry: “My spouse threatened to maim me for life [this morning], grabbed me, threw me across the room. Threw and broke many of my personal items.”

“I am in fear for my life,” she added. “He is twice my size.”

Rachael moved out several times, but kept going back. “I think I had such low self-esteem,” she says. “I don’t think I ever thought that I wanted that. But I guess you kind of accept it in a way, because maybe you think that you’re not worth [something better].”

As Rachael was living through this maelstrom, Trax was foundering. Not long after she got together with Larry, Rachael discovered that the Trax plant was all but deserted. The power had been shut off — Larry was something like $35,000 behind on the electric bill. Larry told the Chicago Tribune that Trax went bankrupt back in 1991, after distributors that owed him $4.5 million went out of business. (How does one live in a swank lakefront apartment while being literally unable to keep the lights on at work? “If he had $10 in his pocket,” Curt Sherman says of his brother, “he’d spend $20.”)

Rachael and Larry had to use AuctionWeb — soon to be renamed eBay — to make ends meet. “Larry was totally on the Steiff thing,” says a longtime friend of the couple, fashion designer Michael White. Steiff: as in the much-coveted, high-end teddy bears. Larry was selling them on eBay for up to $2,000, according to White.

In 2002, a Canadian music-publishing company, Casablanca (not to be confused with the U.S.-based disco label), made them an offer. Casablanca would get licenses to the Trax catalog, which would allow Casablanca to sell Trax music, market it to people making movies, commercials, and video games, and make its own sublicensing deals around the world. In return, Casablanca would pay them $20,000 a month as an advance against revenue from relicensing the tunes (Rachael says that it ended up being $10,000). It would also loan them $100,000, using the label as collateral.

It was a terrible deal, something like gambling the deed to your house on the flip of a coin. But Larry was out of options, and both he and Rachael signed it. Rachael says he forced her to do it.

Larry spent much of the money on state-of-the-art equipment and hiring full-time engineers — which, Rachael protested, they could not afford — for a studio. According to court papers from the time, Casablanca — in addition to the $100,000 loan — paid Rachael and Larry an advance of $367,000.

Larry and Rachael defaulted on the loan, according to a legal filing, and when the licenses didn’t cover the advance, they had to pay the advances back. And when they couldn’t do that, Casablanca collected on the debt. In 2006, the company obtained a court order, and one morning two Cook County sheriff’s deputies arrived at Lake Point Tower with some movers and seized computers, master tapes, filing cabinets, recording equipment, and anything that belonged to Trax. Casablanca put Trax up for auction, but Casablanca itself was the highest bidder. Larry and Rachael were both left out in the cold, with nothing to do but fight desperately to wrest the label back.

The apartment at Lake Point Tower went into foreclosure — which, in one way at least, was a good thing. It meant that Lawyers for the Creative Arts, a group of volunteer attorneys who represent underfunded people in the arts, agreed to represent Larry and Rachael, and began litigation to get Trax back from Casablanca.

Around the same time, Rachael finally left Larry. On April 25, 2006, Dr. Joan M. Anzia, the medical director of the outpatient treatment center of Northwestern Memorial Hospital, wrote a letter urging the courts to grant Rachael an immediate divorce. “Ms. Cain has been a patient of this clinic since 1996,” she wrote. “The patient has been contending with multiple types of abuse since being married to Larry Sherman. These abuses include: physical, sexual, emotional, financial, and also many instances of coercing Ms. Cain to sign legal documents that she did not want to sign. There have been occasions when the patient was handcuffed to a chair and told that if she did not sign documents he would kill her.” (Anzia declined to comment for this story.)

A week after the letter, Rachael and Larry divorced. The former couple were so determined to get Trax back from Casablanca, Rachael says, that they divided it up in the settlement, even though they didn’t even own it at the time.

In 2007, Casablanca licensed the classic Trax catalog to Demon Music Group, a company owned by the BBC that deals largely in entire vintage catalogs, often packaging them up as bargain-bin compilations sold in supermarkets. In 2012, Rachael and Larry got back ownership of Trax from Casablanca, but the deal that Casablanca struck with Demon giving it exclusive rights to the catalog remained in place.

Larry spent the last years of his life at the Paradise Park mobile-home park in Lynwood, Illinois, with Sandyee. He often railed against Casablanca and Demon. The last time Vince saw Larry, in the spring of 2018, Larry had a storefront in Lynwood. Looking thin and weakened, he sat amid industrial pallets full of used vinyl. It looked to Vince like he was buying up inventory from closing-down pressing plants — probably to sell on eBay. Vince had gone out there with a Kanye West associate, and he watched Larry cheerfully “clear” a sample of the Trax cut “Boom Boom,” which West used on “Lift Yourself.” (Vince says that Larry promised him a cut of the payment from West’s team, and then, as if for old times’ sake, didn’t give it to him.) Larry asked about Vince’s son and said he was proud of everything Vince had achieved. Larry died of heart failure in April 2020. Rachael says that she, Tessa, and Sandyee buried him in a cardboard box, in a plot by a highway, across a chain-link fence from a car dealership. His burial was paid for by a Jewish charity that, among other services, puts up money when the alternative is cremation, which traditionally isn’t permitted for Jews.

After she lost the label to Casablanca, Rachael took a year to, as she puts it, “pull herself together,” then around 2007 started a new label, Phuture Trax, with her own roster of artists. She kept writing music, performing, and DJ’ing. She also married a former rodeo rider turned construction executive. (George Clinton was the best man.)

On Jan. 1, 2022, two years after Larry died, Rachael finally got the use of the rights to the classic Trax catalog back from Demon. For the first time, she had the chance to run the label exactly as she wanted. But her problems would only multiply.

LAKE POINT TOWER is a significant address. Famous athletes — Scottie Pippen, Sammy Sosa— have all called it home, as has former Obama adviser David Axelrod. When they let you past reception, toward the elevators, you pass a wall covered by a sheet of falling water. The elevators let out onto a large, empty, bright white room the shape of a triangle with the corners rounded off. It feels like an airlock on the Enterprise or, perhaps, a forgotten anteroom in Kanye’s mind.

Rachael’s address in the building has become a totem of her perceived exploitation of the Trax artists. It’s easy to see how. A window looks down, literally, on the city. But when I visited in January, there were no clean Mies van der Rohe lines; there were ancient sofas hidden with throws. You could shut the bathroom door but not all the way — you’d get locked in. The place is ankle-deep in old tapes and dusty Trax paraphernalia; there were also several display cases of Steiff bears, along with the taxidermied remains of Boss, the Trax warehouse cat.

Rachael’s current husband, the construction executive, has bankrolled her dogged pursuit of Trax. When the bank threatened to foreclose on the Lake Point apartment in 2007, he bought it from Larry for $525,000. He’s thrown a significant chunk of his own fortune into legal fees and other Trax expenses. He recently sold the apartment, which was on the market for $515,000.

The various battles — against Casablanca, against Demon, against Larry, and now against Vince and Jesse and 21 others — have ground on the couple’s relationship. “He’s sick of it,” says Rachael. “It’s almost destroyed my marriage.” (Her husband, who requested that he not be named, declined to comment.) Meanwhile, in November, a promoter for a gig Rachael was due to play took her name off the flyers. Rachael says he told her she’s become a pariah in the house world.

“When [Vince and the other plaintiffs] didn’t help to save this company for all those years, I risked everything,” Rachael says, adding, “What I see is — Vince, you left the label in 1986.… Your name is not on one corporation. You weren’t the one who fought. I was the one who fought.”

Vince says he knew early on that Larry was screwing him and the other artists. He never considered suing. Why? Partly because they couldn’t afford a lawsuit back then, but also because “it’s Uncle Larry.” The Trax kids had a kind of twisted attachment to Larry, according to Vince. Sure, Larry was cheating them, but at least he let them put out their work in the first place — Vince says established Black-owned labels didn’t see the potential in the house sound until long after Larry started making the records.

But now, Uncle Larry is out of the picture. “I think it comes down to the fact that [the artists] were loyal to my dad, not to Rachael,” says Tessa Sherman. “With his name still on Trax, they didn’t have much of a fight against his decisions, and now he’s not here to fight on these decisions.”

To Jefferson, the Trax situation is consistent with systemic, long-standing problems with the music industry. “Any record deal is skewed in the label’s favor to begin with,” he says. “I think our time has just come to stick our feet into the ground, brace ourselves, and go for our rights, man. This happens with every artist. I suspect it happened with Little Richard; it happened with the Chess artists, you know, Muddy Waters. And now it’s happening with us. At a certain point, you just fight for your rights.”

Vince says the Trax fight is about specific people — regardless of their race — who have mistreated some other specific people. But, he says, the fight also takes place in a context that goes back generations and reaches beyond the music industry and Chicago: “Black people have been dealing with the shit end of the stick forever. You can’t get into the club without four IDs. But you don’t stop going to the club. Taking the bullshit is an act of resistance.”

He thinks he didn’t sign papers to protect his share of Trax in the early days because in some, perhaps subconscious, sense he simply never expected a fair deal — so why reach for one? And if he’s not careful, he might teach that to London: “I consciously level the playing field so he understands he can do whatever the fuck he wants.” Part of that lesson, he says, requires getting the rights to his music back from Trax. (“I feel treatment of artists has nothing to do with skin color,” Rachael responds. “There is not a racist bone in my body, and Larry wasn’t racist either.”)

In June 2020, two months after Larry’s death, Ben Mawson’s TaP, the management firm behind Lana Del Rey, bankrolled prominent Trax artists Larry Heard and Robert Owens, who recorded hits including “Can You Feel It” and “Washing Machine” (with Heard using the name Mr. Fingers), to sue Trax for “not less than $1 million.” Trax settled, and Heard and Owens got their rights back.

Vince Lawrence, Jesse Saunders, Marshall Jefferson, and the 20 other plaintiffs filed their case in October 2022. The suit, filed in the Northern District of Illinois, claims Trax “knowingly submitted materially false information to the Copyright Office by claiming ownership in Plaintiffs’ compositions and sound Recordings” — in short, that it claimed it had the rights to the music (and with it the ability to collect royalties) when it didn’t. And, the plaintiffs allege, Trax won’t be able to produce paperwork to prove it owns the recordings. The plaintiffs are seeking $150,000 for each master recording they allege Trax fraudulently registered.

The plaintiffs are also asking the court to “invalidate” the copyright registrations that Trax has claimed, in effect returning — or, they would say, recognizing — the artists’ exclusive ownership of their copyright. The same suit claims that in 2007 Rachael registered the Trax logo with the trademark office even though she knew it belonged to Vince, and that Trax’s registration should be canceled, which would allow Vince to register it.

Trax says either that it has valid contracts or that valid contracts have been lost in its various ordeals, and provided a 1986 contract to Rolling Stone for Jefferson’s “Move Your Body (The House Music Anthem).” (It promises a $6,400 advance with a royalty at 15 percent, among other terms.) Jefferson claims Trax has forged or amended his contracts, including the one for “Move Your Body.”

“Rachael, I think she’s holding onto that catalog out of spite,” Jefferson says. “I don’t think anyone ever respected her talent. So this was Rachael’s revenge.… She really wasn’t that talented, we felt. That’s how I felt.” (“Marshall Jefferson saying that I am hanging on to the catalog out of spite is petty,” Rachael says. “My talent speaks for itself.”)

Meanwhile, even Jesse and Vince don’t seem to be able to agree on the basics — the suit says the two of them founded it with Larry, but Jesse now says via email that he was more focused on music than the label. “I didn’t have a role in Trax,” he said.

Richard Darke, who has been representing Rachael since 2005, says that he believes the resentment against her and Trax is based in part on some significant misunderstandings. “I don’t know how Larry and Rachael treated all the artists, but I do know that in 2007 and on, it really was not Rachael and Larry’s responsibility to pay all these artists,” Darke says. “It should have been Casablanca, and then it should have been Casablanca via Demon.” Rachael, he claims, wasn’t responsible for paying artists until January 2022. (“As much as Casablanca would like to correct impressions about the business dealings of the Trax entities,” said Caren A. Lederer, an attorney representing Casablanca, “these companies were parties to years-long litigation that ended in 2012 with a binding settlement agreement that included a non-disparagement provision.… Casablanca has and will continue to honor this obligation.” Emma Burch, a representative for Demon Music Group, said: “During the period from 2007 to 31 December 2021, Demon Music Group was a licensee of Casablanca Trax Inc. As a licensee, Demon Music Group was not responsible for artist payments. The contractual responsibility for artist payments sat with the licensor or relevant rights owner.”)

On March 6, Sandyee’s attorney asked a judge to dismiss the lawsuit, claiming the plaintiffs don’t allege what musical works were infringed on, “by whom, or … how and/or when” they were infringed, that certain defendants should not have been named in the first place, and that the allegations are lacking in substance. On April 3, attorneys for Trax and Rachael joined them in demanding the case be dismissed for the same reason. The court has yet to respond.

Lita Rosario-Richardson, a Washington, D.C.-based lawyer who specializes in music rights, says Trax and Rachael are in a lose-lose spot. If they can’t come up with valid contracts to support their copyright registrations, they’ll be considered to have filed copyright fraudulently. But if they can come up with the contracts, they’ll owe whatever royalties the artists are due per those contracts. She suspects Vince may have more trouble arguing that he owns the logo, since what matters with trademarks is not so much who owns them as who is using them — and Trax, clearly, has been using the mark that he claims is his.

With the plaintiffs seeking $150,000 per master, a ruling in their favor would almost certainly bankrupt Trax. Rosario-Richardson suggests Rachael’s best move may be to settle — much as with Heard and Owens — and hope to simply “return” the rights to the artists without paying damages.

As if all that wasn’t complicated enough, the legal situation behind the suits is decidedly messy: Greg Roselli, who represents Sandyee, used to be Rachael’s attorney, and before Mulroney, Vince’s attorney, sued Trax, he represented a buyer in an aborted attempt to purchase the label. Meanwhile, Roselli hopes to set up Trax in the U.K., where he’s based, and Mulroney has suggested that he himself might be the general counsel for a new, Vince-led Trax, should their suit skittle Rachael out of the way. (Roselli, as Sandyee’s attorney, says, “As to the future, Sandyee Sherman’s vision is to reestablish the label by working things out with the Trax legendary artists.” Mulroney said, “The artists will decide who they want to work with, and I do hope I will be part of it.”) Meanwhile, Rachael and Sandyee are suing each other, Rachael is suing one of the lawyers, and there are various disputes over the divorce settlements and will.

Despite Mulroney’s suggestion of a new Vince-led Trax, Vince — who owns a studio and already has an organization, Slang Music Group, that provides music for commercials and movies — says that he doesn’t want to “take over” the label. “I just want people to have what belongs to them,” he says.

Rachael — who has only had full control over the classic catalog since Jan. 1, 2022, when she got the use of it back from Demon — says that part of the terms of the return of the rights was a fund of approximately $100,000 to be divided among the artists. She also says that 50 percent of the income from those tracks since January 2022 has been put in escrow to be distributed among the artists, and has sent out letters to classic Trax artists asking for tax documents that would allow them to be paid. She says Trax has also engaged royalties-accounting firm Infinite Catalog to manage the distribution of payments.

The theory among some in the Trax camp is that when Demon handed the catalog back to Rachael last year, it didn’t do so out of generosity. Demon knew, the theory goes, that litigation might be coming and, perhaps, that the perception that the venerable BBC, Demon’s parent company, was stiffing artists would be scandalous. (Demon responds: “This is factually inaccurate. Demon Music Group, as licensee, not rights owner, provided all relevant royalty statements directly to its licensor, Casablanca Trax Inc., and the rights owner was responsible for making artist payments.”)

Rachael is heartbroken, but she’s not letting go. “When I started the journey, no one, absolutely no one, believed I could ever win against Casablanca.… I am the only person who just believed in persevering, and somehow all that finally ended only to start this new terrible chapter,” she says. “There were so many times in my life where I’d be losing everything. Losing people I love; losing everything I have. And now it’s happening again.”