A lawsuit filed this week accuses the director of a San Francisco nonprofit that shelters and feeds homeless people of misusing funds to support a “lavish” lifestyle while drug use and prostitution allegedly went unchecked at the organization’s housing sites.

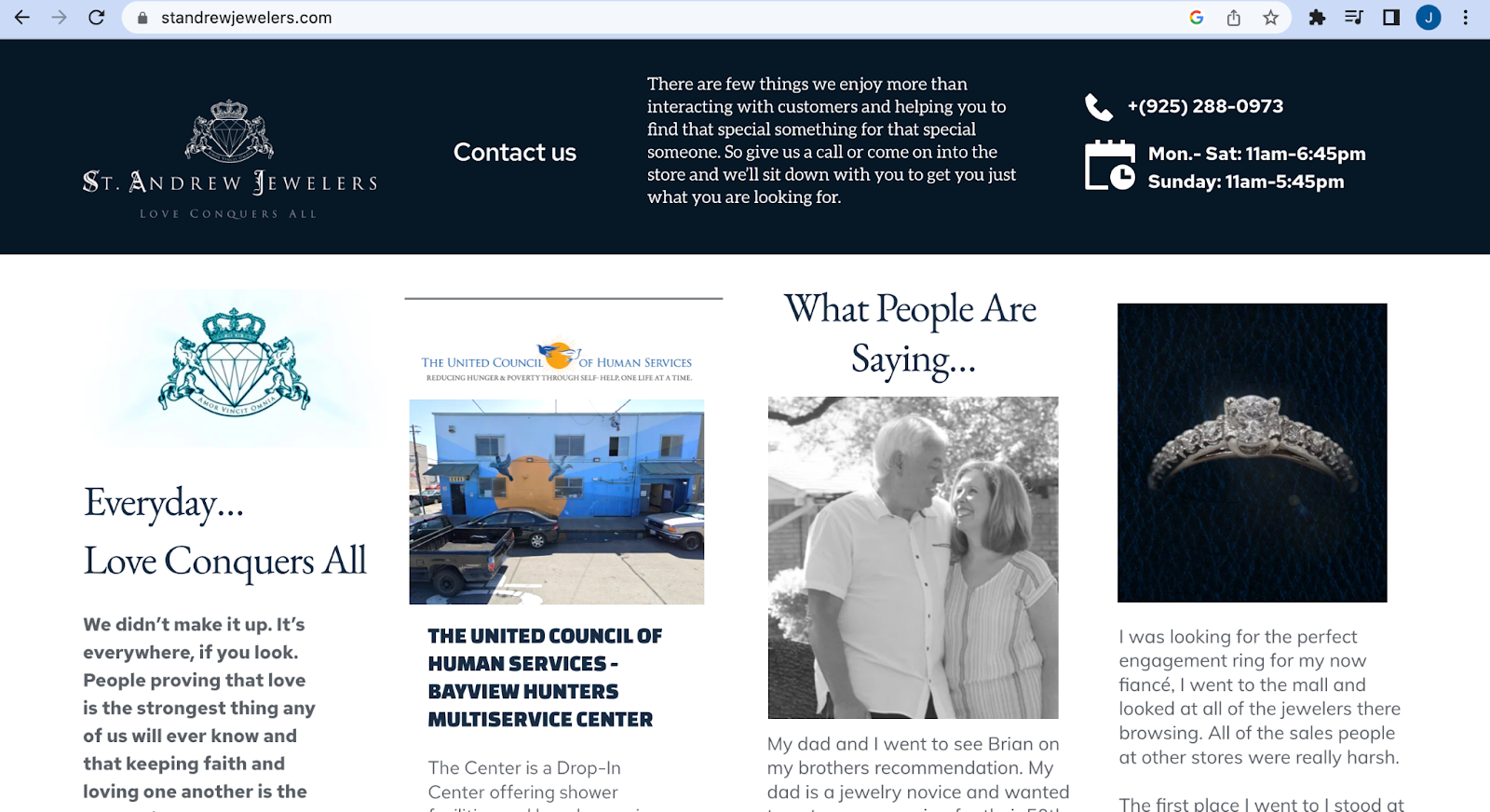

The complaint against the United Council of Human Services (UCHS)—formerly known as Mother Brown’s Kitchen—and its CEO, Gwendolyn Westbrook, was filed Wednesday in San Francisco Superior Court and comes just a few months after a city audit raised red flags about the organization.

UCHS has received tens of millions of dollars in city and federal grants over the last two decades, but its use of those funds was poorly documented, according to city officials. In November, City Controller Ben Rosenfield and City Attorney David Chiu wrote a letter to the FBI and District Attorney’s Office urging the agencies to open a criminal investigation into UCHS, which had its charitable status suspended by the state Attorney General’s Office last summer.

Noel Robinson, who worked for the organization and is the plaintiff identified in court filings, accuses Westbrook of “living a lifestyle inconsistent with her reported salary,” which was $155,000 a year in 2015.

Westbrook allegedly told staff that she has purchased and paid off multiple vehicles in recent years, including a Tesla for herself, a Jeep Renegade for a close family friend, and two vehicles for cousins while also gifting an Infiniti SUV to a niece. Meanwhile, the lawsuit states, Westbrook was known to drive around with “a trunk full of high-priced jewelry” that was obtained from one of the nonprofit’s board directors.

Brian Berglund, the board director and the owner of St. Andrew Jewelers in Concord, did not respond to a message left with the business requesting comment. However, the company’s website has a note about UCHS’s work in between testimonials and a promise to help customers “find that special something for that special someone.”

Other notable expenses in the complaint include Westbrook allegedly paying for multiple in-vitro fertilizations for a relative and family members’ weddings.

Forms filed with the IRS show that UCHS has routinely failed to disclose how large sums of money were spent, and the lawsuit notes that a federal tax form from 2019 showed $2.1 million in “other” expenses that were not detailed as required by law. The Standard reviewed UCHS tax filings with experts who said the accounting raised “huge red flags” and showed “incompetence.”

In 1997, Westbrook pleaded guilty to stealing thousands of dollars in parking lot collections from the Port of San Francisco.

Robinson said he was suspended and eventually fired in May of last year after raising concerns about the behavior of Westbrook’s nephew, who became a UCHS resident and employee after getting out of a Texas prison. Westbrook previously told The Standard that around 20 of her friends, family and employees were occupying housing that is designed to go to San Francisco’s neediest residents. The city controller’s audit found that some UCHS residents did not go through the proper protocols to gain access to housing.

Westbrook’s nephew allegedly started confrontations with Robinson and others at a recreational vehicle (RV) housing site at Pier 94 in addition to consuming drugs on the property and bringing in sex workers. The complaint notes that Robinson raised these concerns with Westbrook on multiple occasions, but he was told to “leave my motherfucking nephew alone!”

The organization saw its city funding skyrocket last year, according to the complaint. On Feb. 1, the city issued six new grants worth $36.4 million to the Bayview Hunters Point Foundation, a nonprofit that serves as the fiscal sponsor for UCHS and was named as a defendant in the complaint. The grants included almost $10 million in funding for the Pier 94 site where the alleged drug use and prostitution occurred.

“[Robinson] feared the self-dealing practices he and others had observed in Westbrook and her inner circle would not only continue, but increase and threaten the future of the Pier 94 shelter he had spent two years building and protecting,” the complaint says. “Conversely, Westbrook and the Company appeared to recognize the threat a whistleblowing employee would pose to the increasing grant money.”

Robinson said he has suffered physical and emotional distress since he was fired last spring, and Westbrook allegedly began spreading false rumors about him. He is seeking damages for wrongful termination, retaliation and defamation, among other claims. Past fiscal sponsors for UCHS, including the Bayview Hunters Point Foundation and Heluna Health, were also named as defendants.

However, Bayview Hunters Point Foundation officials told The Standard that it recently came to a settlement agreement with Robinson and rehired him.

Westbrook declined comment when reached by phone Thursday afternoon.

Shawn Richard, a deputy director for UCHS, called The Standard on Thursday evening and disputed the allegations in the lawsuit, noting that an internal investigation found that Robinson was the one violating the law.

“Noel was doing something illegal he shouldn’t have been doing and it got back to [Westbrook],” said Richard, who did not start working for UCHS until October of last year. “He felt he could just do what he wanted to.”

The complaint states that Westbrook falsely told people on multiple occasions that she had fired Robinson for stealing Capri Suns, calling her a “bitch,” selling trailers and drugs, and “trading Company property for sex with homeless women.”

An attorney for Robinson declined The Standard’s request for an interview.

Richard said that Westbrook “never was in control of the money” for UCHS and city officials have blown matters out of proportion in calling for a criminal probe involving the FBI.

“There’s always two sides to every story,” Richard said, “and actually there’s four sides—because there’s four sides on every corner: the truth, the lie, the middle and the person who really knows what’s going on.”