It’s well known that I don’t pay much attention to sports.

The most I knew about Kansas City’s football team is that Taylor Swift’s dating choices have caused a lot of grown men to have conspiracy-fueled meltdowns.

But my ears perked up at a news meeting last week when we were discussing the upcoming Super Bowl and the teams playing were the “Chiefs” and the “49ers.”

While I don’t track much about football, I did follow closely the long, grueling effort to change the name of the pro football team in the other Washington.

I remember in 2014 when The Seattle Times banned the use of the team’s name, which was a racist slur to describe Native American people. Way back in the 1990s, the paper had already restricted the use of the name to one per story and kept it out of headlines and photo captions.

Finally, in 2022 — after two years of being called simply the Washington Football Team — the team rebranded as the Washington Commanders.

I knew that change was made after decades of advocacy by Native people and allies and that the Cleveland baseball team had also changed its name from the “Indians” to the “Guardians,” so I was surprised to hear Kansas City still had a Native team name in 2024.

The history of the Kansas City team’s name got weirder and weirder the more I looked into it. Proponents of keeping the name argue that it’s not offensive because it’s not connected to any particular tribe and is named after a white man named Harold Roe Bartle, the former mayor of the city, who called himself “Chief.”

Giving that argument the benefit of the doubt, I dug into it further and found that the reason he had that moniker is because he was the founder in 1925 of a fake Missouri tribe — associated with the Boy Scouts — that he called the Mic-O-Say Tribe and he claimed the name “Chief Lone Bear.”

Bartle had a penchant for wearing faux Native regalia and cultural appropriation. The invented “tribe” he founded still exists today, along with much of the same audacious cultural appropriation of its founder.

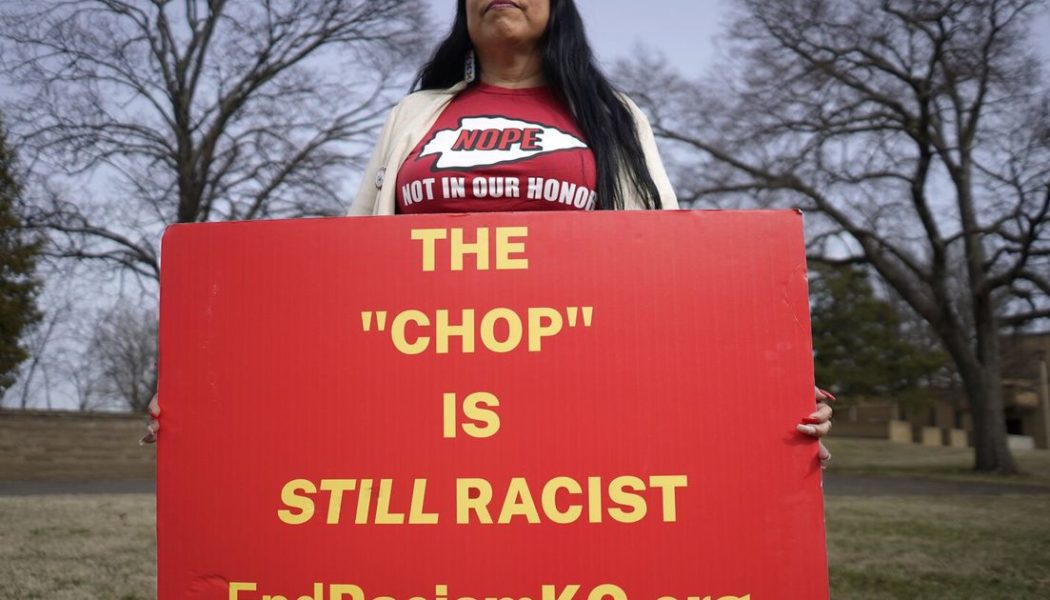

Native-led organizations have fought to have the Kansas City team’s name changed for years. Since 2005, a Kansas City group called Not In Our Honor has protested the team name and its assortment of offensive accoutrements, including the tomahawk chop gesture and chant, face paint and fake headdresses. They placed billboards, along with the Kansas City Indian Center, in 2023 reading “Change the Name and Stop the Chop.” Not in Our Honor planned a protest at the Super Bowl Sunday as well to push for change.

Professor Stephanie Fryberg (Tulalip), is one of the nation’s leading scholars on the psychological impact of Native mascots. She co-led a study published in 2020 that found 49% of the 1,000 Native respondents agreed that the former name of the Washington Commanders was offensive, a number that increased to 67% for people who were “heavily engaged” in their Native or tribal cultures. Her work is in contrast to sunnier Native mascot opinion polls that she described as “used to silence Native people.”

In an earlier paper she co-authored titled “Of Warrior Chiefs and Indian Princesses: The Psychological Consequences of American Indian Mascots,” she argued the outsized impact of Native mascots is exacerbated by the scarcity of Native representation.

“The relative invisibility of American Indians in mainstream media gives inordinate communicative power to the few prevalent representations of American Indians in the media,” the paper said. “One consequence of this relative invisibility is that the views of most Americans about American Indians are formed and fostered by indirectly acquired information (e.g., media representations of American Indians).”

Stereotypes and caricatures of Native people are widespread in the form of Native mascots and team names, with an estimated 2,000 still existing in the U.S., including on the largest stage in the land, the Super Bowl.

Washington banned Native mascots in 2021 with some exceptions.

University of Washington lecturer in American Indian Studies, iisaaksiichaa ross braine, a citizen of the Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation of Montana and a doctoral student in the Information School, teaches students about the harm of Native mascots.

Braine said Native people have been dehumanized from the founding of the country. Described in the Declaration of Independence as “merciless Indian savages,” he said Native mascots persist “because of systemic racism … power, privilege, position and profit.”

He said he knows many will say “it’s just a game, get over it,” but that attitude ignores the real harm stereotypes create. He said the mascots are misappropriated and “rooted in antiquated, fictitious and racist — if often romantic — notions of Indianness. It is rooted in that racist and old way of seeing people.”

Yet braine said it’s important to recognize how much progress has been made in Washington and beyond when it comes to Native mascots. Seattle University changed theirs, West Seattle High School and Bishop Blanchet High School did as well.

“It can be done. It is not an impossibility,” braine said. “The impossibility should be keeping Natives as mascots and dehumanizing them forever.”

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews